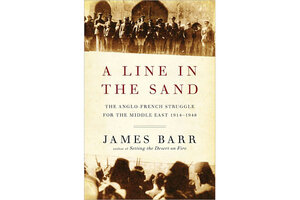

A Line in the Sand

An unsettling history of British and French machinations in the Mideast.

A Line in the Sand

The Anglo-French Struggle for the Middle East, 1914-1948

By James Barr

W.W. Norton

352 pp.

Much is always made of the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 in which the British and the French secretly connived to split the Middle East like a ripe melon, dividing what is now Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordon, Israel, Gaza and the West Bank between them. The fact that neither controlled or had any legitimate right to this vast expanse was of little import in London and Paris; they planned to seize control of it soon enough from the waning Ottoman Empire.

It was a facile agreement, to be sure, and dramatized the mad scramble for the region and its resources, but the game was already on when Sir Mark Sykes, a 30-something baronet who passed himself off as a Middle East expert, drew his infamous line in the sand connecting Acre on the Mediterranean coast with Kirkuk in the heart of what was then known as Mesopotamia. Decades previously Britain had taken control of Egypt and Cyprus, and World War I would be the catalyst for gathering more low hanging fruit. The security of the Suez Canal and access to oil, the fossil fuel of the future, were the prime motivations. Wherever the line was drawn, the Middle East was in for big changes.

In his second book, A Line in the Sand: The Anglo-French Struggle for the Middle East 1914-1948, James Barr vividly portrays the convoluted and often deadly game played by these ostensible allies. The locals were often a sidelight to this main event. If the Arabs were revolting in the Levant against the French, the British could hardly have been less helpful. Later, when the Zionists rose against British rule in Palestine, it was the French who were blasé, and then some – indeed, many were only too happy to aid Jewish terrorists bent on killing Britons.

The Brits may have helped France twice against the Germans, but they weren’t as keen on sharing the Middle East with their historic rival. France, for its part, was desperate to regain its pride and status as a world power after a bumpy century highlighted by its humiliating collapse in World War II. At times, the Syrian front seemed more important to Frenchmen like Charles DeGaulle than the fight against Hitler.

To make matters more confusing, when the British and the Free French invaded Syria in 1941, the Vichy French forces in control of Damascus fought their fellow countrymen with a vengeance. In 1945, when the British intervened to stop French efforts to put down a Syrian revolt, DeGaulle seethed, telling a British official: “We are not, I admit, in a position to open hostilities against you at the present time. But you have insulted France.... This cannot be forgotten.”

Barr, who is a British journalist, depicts the tenor of Anglo-French antipathy with telling research, engaging profiles of key players, and entertaining anecdotes. Of Sykes’ French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, he writes, “The British, in whom Georges-Picot’s ‘fluting voice’ and condescending manner triggered an allergic reaction, pointedly ... called him plain old ‘Monsieur Picot.’” Touché.

While Barr travels some well worn historical territory, his use of recently declassified government materials infuses new details into the depth of the geopolitical intrigue that helped to form – or deform – the modern Middle East. Colonialism in the 20th century needed to be a bit more politically correct than it was during the unashamed scramble for African colonies in the previous century. When the Bolsheviks make the Sykes-Picot Agreement public in 1918, the embarrassed British and French made the proper noises about helping the people of the region transition to self-rule.

But mainly they rigged what few elections or plebiscites that were held to install accommodating Arab rulers. The British established Sunni leaders in Iraq to rule a majority Shiite population and included in the newly created nation Kurdistan and the city of Mosul, which was well north of the Sykes-Picot line, not because it made sense for the locals but because there was oil up yonder. The British, in Orwellian fashion, also changed sides based on strategic considerations.

Supporting Zionism seemed like a good means of projecting influence in 1917 in Palestine, but by 1939, with Germany threatening the Middle East, the Arabs were deemed a better bet. British policy changed accordingly.

What was good for Britain and France – or what was perceived as such by them – was seldom good for the people in the region. Barr sums it up nicely: “Britain’s sponsorship of the Jews in Palestine and France’s favoritism of the Christians in Lebanon were policies designed to strengthen their respective positions in the region by eliciting gratitude from both minorities. The appreciation they generated by doing so was short-lived, but they deeply antagonized the predominantly Muslim Arab populations of both countries, and the wider region, with irreversible effects.”

David Holahan is a regular contributor to the Monitor’s Books section.