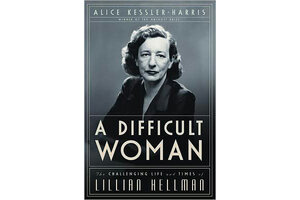

A Difficult Woman

Historian Alice Kessler-Harris attempts an artistic, political, and moral portrait of a challenging subject: Lillian Hellman.

A Difficult Woman:

The Challenging Life and Times of Lillian Hellman

By Alice Kessler-Harris

Bloomsbury USA

448 pp.

At Hardscrabble, the farm in Pleasantville, N.Y. she’d bought after the success of "Little Foxes," Lillian Hellman slaughtered animals, made sausage and headcheese, hunted, trapped turtles, and fished. She surrounded herself with famous guests of all sorts, and worked diligently on her plays. The place, aptly named, witnessed the flowering of her many-sided persona: as a best-selling playwright and memoirist, and as a celebrity with an outsized social and political life.

It is a life that’s been both celebrated and reviled, and one that proves a doughty challenge for the biographer. In A Difficult Woman: The Challenging Life and Times of Lillian Hellman, historian Alice Kessler-Harris tries a new approach, attempting a kind of portrait, through Hellman, of 20th-century artistic, political, and moral life. Hellman – Southern Jew, independent woman, and erstwhile communist – intersected with many flashpoints of her time. Kessler-Harris takes her as a historical lightning rod, her “identity woven into the fabric of political debate.”

History allows Kessler-Harris to forgive. She writes that the labels Helman received – unrepentant Stalinist, self-hating Jew, liar – as well as her reputation for being rude and vindictive, emerged less from her beliefs and practices than from the public mind-set at the time they were applied. Hence, while “in the sharp glare of history, neither the act of signing [a letter defending Stalin’s purge trials] nor her failure to repudiate the document thereafter is defensible. But by the dim light of the 1930s, both acts are understandable.”

This charitable understanding, though tempered by rigorous detail, can, in the case of personality smack of historical determinism, and fail to give Hellman herself her due. So, if Hellman appeared needy and emotionally dependent, “surely this is linked to the devastating betrayals of the McCarthy period and the dissolution of many friendships under the stress of government investigation.” This is generous, yet maybe overly so – the line between explanation and explaining away is a thin one.

The book is organized by theme, in chapters detailing, for instance, Hellman’s unconventional love life, her plays, and her HUAC hearing. Placing her each time in a different context, the division is part of Kessler-Harris’s project, to “explore not only how the world in which Hellman lived shaped the choices she made, but to ask how the life she lived illuminates the world she confronted.” Hellman’s negotiation of gender roles, for instance, shows the difficulty for a woman of the time to both work in traditionally male fields and yet remain feminine.

These thematic chapters produce a telescoping effect, as all the related episodes of Hellman’s life are stacked against the subject on hand, regardless of chronology. Often, this forces repetition. So, on page 139, after a chapter detailing Hellman’s romantic entanglements, Kessler-Harris reminds us of “Dashiell Hammett, who became Hellman’s lover and partner after 1931,” and halfway through the book, we are told that Hellman earned “her living as a writer for the theater and for the cinema.” Despite the fact that Kessler-Harris is clearly trying to layer our understanding of Hellman’s life by reading it successively through the spheres in which she moved, the approach could have been made sharper by more aggressive editing.

Much of the controversy surrounding Hellman’s name comes from the accusation of lying that she faced late in life: Mary McCarthy famously declared that “every word [Hellman] says is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’” The sound bite, nasty enough to stick, contains some truth: Hellman’s memoirs do misrepresent the facts, engage in mythmaking, and deal with desire as often as actuality. Hellman’s memoirs purposefully claim no control over experience; they recognize the interplay of life and desire.

Yet Hellman was also a truth-teller and moralist, who didn’t hesitate to point out to others when they strayed. This is one of her central contradictions, and while Kessler-Harris tries to locate it too in history, it is more of a problem of genre rather than time – as recent scandals surrounding John D’Agata and Mike Daisey show, such questions are still with us.

The title of "Pentimento," Hellman explained, is taken from painting: “Old paint on canvas, as it ages, sometimes becomes transparent. When that happens it is possible, in some pictures, to see the original lines: a tree will show through a woman’s dress, a child makes way for a dog, a large boat is no longer on an open sea. That is called pentimento because the painter ‘repented,’ changed his mind. Perhaps it would be as well to say that the old conception, replaced by a later choice, is a way of seeing and then seeing again.”

One might say that this is what Kessler-Harris has tried to do, writing Hellman onto various layers of history to see what shows through. Her book, nuanced as it is flawed, is a way of seeing Hellman again, and of possibly changing our minds.

Jenny Hendrix is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn.