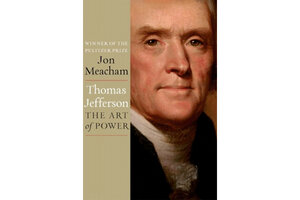

Thomas Jefferson

Biographer Jon Meacham captures Thomas Jefferson as a person, not just a historical figure.

Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

By Jon Meacham

Random House

800 pp.

A popular biography of such a well-trod subject as Thomas Jefferson – contained in a single, not overly long, volume – will leave things out. And in this case, the author makes no pretense to new scholarship. But the approach has advantages if well executed. Jon Meacham pulls it off neatly in Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, focusing on what matters, on the overriding issues and events as well as telling trivia. He captures who Jefferson was, not just as a statesman but as a man.

By the end of the book, as the 83-year-old Founding Father struggles to survive until the Fourth of July, 1826, the 50th anniversary of his masterful Declaration, the reader is likely to feel as if he is losing a dear friend. Jefferson just makes it, dying on that fateful day. I warn you, there may be tears.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning author honored for a similar treatment of Andrew Jackson, Meacham proclaims his subject “the most successful political figure” of his time. He might have gone further, tagging him as the most important political figure in our history. Beyond his contributions to the Revolution and to America before his defeat of President John Adams in the election of 1800, President Jefferson showed masterfully that the other party could take over and run the country for two terms – change some things, keep others the same – without the world going to rack and ruin. In brave new democratic experiments, the first such transfer of power is always the trickiest.

It was a time of unusual partisanship. George Washington was appalled by it. Today’s squabbles are halcyon by comparison: editors were jailed along with a Congressman for speaking their minds; Jefferson’s Vice President was under indictment for murdering Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist opponent, in a duel; and secession (Northern) was openly contemplated.

Jefferson’s Republicans, ancestors of today’s Democratic Party, believed that the Federalists secretly favored the return of British rule or monarchy in some form. Hamilton and his fellow travelers charged Jefferson with fomenting a “Mobocracy.”

Yet Jefferson ruled and America survived; indeed, it thrived. He did it with reason and the written word (he was a poor orator), and harvested votes with his charm rather than arm-twisting. Sworn political enemies almost always came away from encounters with this accomplished, affable man with at least grudging respect.

From 1801 to 1809 America would double in size, stay out of a war with Britain, become more fiscally and militarily sound, and get to know its continent better thanks to Lewis and Clark as well as to its leader’s inquisitive nature. It was hard to argue with those outcomes, and most Americans didn’t. They elected Jefferson and Jeffersonians for decades to come: Madison, Monroe, and Jackson.

Of course, there were non-political sides to this complex man, some quite engaging and surprising. He would get up every morning and plunge his feet into a bucket of cold water. He kept pet mockingbirds, and for a spell, two grizzly bear cubs in the White House. One of his first acts as President was to banish the outhouse from the lawn and install thoroughly modern water closets inside. He was prone to bouts of diarrhea and migraines. He spoke several languages, played the violin, designed his own house, and sang at the drop of a hat. He believed in America and its people, valued science, and always felt America’s future was bright. Into his 80s, he would ride his horse alone about the wilds of Monticello. He was one optimistic individual. His accomplishments and talents were enough to make a modern person muse, never mind Joe DiMaggio – where have you gone, Thomas Jefferson?

There were shortcomings, too. He slept with the help. After his wife Patty died, Jefferson took up with her half-sister, Sally Hemings, a slave girl of 14 who was the child of Patty’s father and one of his slaves. She would bear six children by him. To get her to leave France with him in 1790, where she could have legally applied for her freedom, Jefferson agreed to her demand that he free her children at 21 years of age. And although he kept his word, he freed only Hemingses. The rest were sold upon his death along with his other possessions to pay his substantial debts.

Clearly troubled by slavery from early adulthood and expressing hope that time somehow would remove it from American society, Jefferson never engaged this issue head-on as he did so many others that were important to his country. Other Founding Fathers and revolutionaries set better examples: For example, George Washington freed his slaves in his will; and Lafayette urged Jefferson to be more proactive, to no avail.

At times in this absorbing tale the reader wishes for more or can see the downside of a swift moving narrative – for example, when Americans forces are credited with the victory at Yorktown, where the French played no small part. Or take the paragraph that describes the episode in 1786 when Jefferson and John Adams were invited to court by King George III, who could not have been “more ungracious,” according to Jefferson. This is way too juicy an historical moment to pass over so quickly.

What a life our third president led. For example, he witnessed two revolutions unfold before his eyes, one American and the other French. In the end, of all the things that make Jefferson remarkable and set him apart from the modern subspecies of politician, these are perhaps the most telling: he would risk all, his life and fortune, in 1776 for what was best for his country, and during his presidency he would grow considerably poorer as the nation flourished. How many of our leaders today can say half as much?

David Holahan is a regular contributor to the Monitor's Books section.