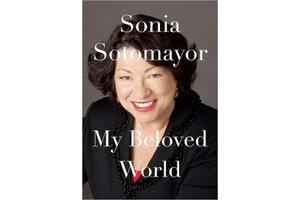

My Beloved World

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor tells her story with wit and candor.

My Beloved World

By Sonia Sotomayor

Knopf Doubleday

336 pp.

It’s hard not to indulge in clichés when describing Sonia Sotomayor. Diamond in the rough. Rags to riches. Working-class hero.

Yes, she ascended from the South Bronx to the US Supreme Court. And along the way, she broke ground for fellow Hispanics and women at Princeton and Yale. But read her new memoir, My Beloved World, and you’ll see in Sotomayor a surprising wealth of candor, wit, and affection. No topic is off limits, not her diabetes, her father’s death, her divorce, or her cousin’s death from AIDS. Put the kettle on, reader, it’s time for some real talk with Titi Sonia.

In 1954, she’s born to Puerto Rican immigrant parents and grows up in the downtrodden projects of the Bronx. At the age of 8, she’s diagnosed with diabetes and is told she must have a shot of insulin every day. Alcoholism has left her father’s hands too shaky for the task, so she learns to do the injections herself.

When she’s 9 years old, her father’s struggles are over – he dies because of health complications. “From here, Mami, Junior, and I would be going along without him. Maybe it would be easier this way,” she says.

She’s half-orphaned now, living in a neighborhood rampant with drugs and junkies: “One by one the shops would darken, and we could hear the clatter of the graffiti-covered gates being rolled down, trucks driving off, until we were the only ones walking. Even the prostitutes had vanished.” However, Sonia takes refuge in her “beloved world” – her caring community made up of her immediate and extended family.

The author shines in her passages on childhood, family, and self-discovery. Her magical portraits of loved ones – especially her abuelita (grandmother) – bring to mind Sandra Cisneros’s “The House on Mango Street”; both authors bring a sense of childlike wonder and empathy to a world rarely seen in books, a Latin-American and womancentric world.

She addresses her chronic health condition, which she says presents bittersweet blessings. One is “a fine-tuned sensitivity to others’ emotional states” that comes from “mentally checking [her] physical sensations every minute of the day.” Another is her motivation to succeed. “I probably wasn’t going to live as long as most people, I figured. So I couldn’t afford to waste time.”

So how does she – a Puerto Rican girl who grew up working-class, who rarely spoke English as a child, and who has no one to chart a path for her – get into college, let alone law school? She says, “I’ve sought out mentors ... soaking up eagerly whatever that friend could teach me.” This isn’t a story of pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps. This is a story of a child seeking a village to raise her.

After high school, she advances to Princeton with a full scholarship. In contrast to the Bronx, the ivory tower is homogenous and privileged. Few women, let alone women of color, grace the campus. And when she notices her lack of worldliness among these elites, she quips, “I was enough of a realist not to fret about having missed summer camp or travel abroad.” We see her self-deprecating humor here as she speaks of never having seen a couch that wasn’t covered in plastic and, later at law school, never having heard of voir dire. (“What does ‘wah-deer’ mean?”)

At each turn, we root for Sotomayor, not only because she’s an underdog but because we know she’s paving the way for future students of color. “Minority kids had no one but their few immediate predecessors: the first to scale the ivy-covered wall against the odds,” she writes. “We would hold the ladder steady for the next kid with more talent than opportunity.”

Sotomayor ascends ever higher, as a law student at Yale, as an assistant district attorney in New York, as a lawyer at a private law firm, as New York State’s first-ever Hispanic federal judge, and, in 2009, as the first Latina US Supreme Court justice. But when her cousin Nelson dies of AIDS, she says, “Why did I endure, even thrive, where he failed, consumed by the same dangers that had surrounded me?”

The question haunts her. But she says, “I’ve spent my whole life learning how to do things that were hard for me.... I’m not intimidated by challenges. My whole life has been one.” In part, her family’s love gave her the support to set her sights beyond the Bronx. In part, each against-all-odds success inoculated her for the next challenge. But most important, her advocates were always by her side. And, with this intimate narrative, it feels as if she is by ours.

Grace Bello is a Monitor contributor.