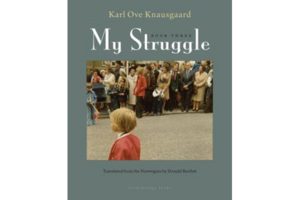

'My Struggle, Book Three: Boyhood' continues the sprawling odyssey of an unlikely Norwegian folk hero

The obscure Norwegian writer has taken the literary world by storm with his six-volume, 3,000-page epic of the quotidian.

My Struggle, Book Three: Boyhood,

by Karl Ove Knausgaard,

translated by Donald Bartlett,

Steerforth Press,

432 pp.

"We all have a private life,'' a teacher scolds young Karl Ove in Book Three of Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle. ''Do you know what that is?'' The seven-year-old eponymous hero has just blurted out that a classmate's father was drunk. The teacher takes him aside. ''It's everything that happens at home, in your home…. If you see what happens in other people's homes, it's not always nice to tell others.'' Karl Ove begins to cry with shame. ''Don't be upset,'' his teacher consoles. ''You didn't know. But now you do!''

If the young Knausgaard took in this lesson, the adult has turned it on its head. In the past two years, the obscure Norwegian writer has taken the literary world by storm with his six-volume, 3,000-page epic of the quotidian. It is a book about time and death, consciousness and regret, but also people – real people: the author's family and his ex-wife, his children, his literary enemies and friends. All of them are laid bare with a ferocious attention to detail. The books were such a sensation in Norway that the author's name became a verb, "to Knaus" – meaning to relate every real experience to a scene in Knausgaard's work.

There are some Norwegian innovations that have bypassed the rest of the world – lutefish, the national dish of salt cod soaked in lye, comes to mind. Knausgaard's cycle is, however, poised to become a true global sensation, and though it may not be for everyone – who wants to read long passages about a man reminiscing about his childhood habit of delaying bowel movements for pleasure? – there is an utterly unique genius to the books.

Inspired by Marcel Proust's multivolume masterwork, "My Struggle" is a memory song for the 21st century. In it the author has taken a long deep look into the past and attempted to braid it into something artful, and permanent, even as philosophically he knows in the end death will take everything. The great project begins with one of the most arresting riffs on death and dying in any contemporary fiction. ''For the heart, life is simple: it beats for as long as it can. Then it stops.''

But there is a fundamental difference in perspective that separates the two projects. Where Proust was an aristocrat, a melancholic, his imagination ignited by cathedrals and family legends, Knausgaard is a middle-class boy, raised in the 1970s with the accompanying existential nihilism. His signifiers are Dr. Doolittle and Wolvertam soccer club, not the subtleties of French pastry. Most significantly, in Knausgaard's Norway – which passed years building up to a sudden and overwhelming burst of oil and gas wealth – there is no such thing as the past:

"Since everything happens for the first time in every generation, and since this generation had broken with the previous one … in our heads we were 1970s people…. And our feelings, those that swept through each and every one of us living there on these spring evenings, they were modern feelings, with no other history than our own. And for those of us who were children, that meant no history. Everything was happening for the first time."

The result of this philosophy is an attention to detail so precise as to shock. The first two volumes of "My Struggle" involved, at the least, a certain degree of narrative drama. Book One opens with the writer at his desk, embarking on the project of understanding his past. ''Today is the 27th of February. The time is 11:43 pm. I, Karl Ove Knausgaard, was born in December 1968, and at the time of writing I am 39 years old. I have three children – Vanja, Heidi, and John – and am in my second marriage, to Linda Boström Knausgaard.'' Knausgaard's overbearing, abusive father has left their family and drunk himself to death.

With two books to his name, Knausgaard sets off to write something great, and in Book Three he has burrowed to the center of it all: his childhood. "My Struggle: Book Three" unfolds mostly during the year Karl Ove turns seven, and his family moved to a forest far from the larger cities in Norway. It is not an idyllic environment: abandoned cars litter the forest bogs, there's a windy danger to the roads, and Karl Ove's mother works at a nearby mental institution. There's a sense Eden has already fallen. Developments have spring up and there are power lines, quarries, the creep of man's destructive hand in evidence everywhere.

But the worst force of all in this personal cosmology is Karl Ove's father, with his free-ranging rage and irritation. And even worse: his sudden, brief bouts of kindness, to prove he is always capable of being good. Virtually anything can set Karl Ove's father's temper off: the wrong posture, a too-happy smile, household items not returned to their rightful place, tears. Karl Ove cannot help but weep copiously. He sobs when he misses the toilet bowl while urinating, he sobs when he must wear a ladies' swim cap to swimming practice. He sobs, constantly, in dread. To read about these fits for hundreds of pages should feel like sitting on a long-haul airplane flight and listening to a child pierce the recycled oxygen with its cries. Instead, somehow, miraculously, it's mesmerizing.

Much of Knausgaard's success emerges from his preternatural ability to enter the mind of a seven-year-old. The magic and the outsize scale of things is there in every detail, and the sense that the world is animate, sentient. As the book lengthens, Karl Ove grows to know the gullies and creeks and bogs around him, just as he does his own mind. He develops a sense of defiance, dropping rocks from a bridge onto passing cars, even though he knows this will be horrendous if (and when) one actually hits a vehicle. He falls in love, and in those passages the book loosens its morose part of its grip on the author, and we can see the innate capacity for joy his father has set to work smothering.

The title of "My Struggle" comes from Hitler's infamous book. It was an attention-grabbing gesture on Knausgaard's part, this title, but once he has our focus he begins re-engineering what we think of when we hear that phrase. For Proust, style was a struggle, a way to be, in the parenthetical richness of his sentence, as complicated a person as he was in life. For Knausgaard the struggle is actual; it is with his family, the deadening quality of certain family routines. It is the struggle to retain the scintillated consciousness this book celebrates in its rush of detail.

Washing a car with the windows rolled down, Karl Ove remembers, made it ''look like a small, plump airplane;'' he remembers the smell of the forest. He remembers the ritual showering before getting into the swimming pool. ''Then the process was reversed and we went from being pale, fragile, semi-naked boys to once again standing fully clothed in the winter outside, with wet hair under our hats and the smell of chlorine on our skin.'' We've all, in a sense, been there: the achievement of Knausgaard's edifice of memories is how powerfully it elicits our own. Sentence by sentence, this incredible book brings it all back, not just for him but for us.