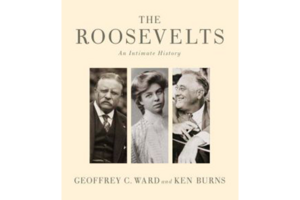

'The Roosevelts: An Intimate History,' by Geoffrey Ward and Ken Burns, makes a gorgeous companion to the PBS series

Theodore, Franklin, and Eleanor Roosevelt believed that they could do great things – and succeeded more often than not.

The Roosevelts:

An Intimate History,

by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns,

Knopf Doubleday,

528 pp.

It would be hard to name three people who had more of an impact on their time than this trio had on the 20th century: Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Eleanor Roosevelt. The two men occupied the White House for 19 of the first 45 years of the "American Century," as Henry Luce dubbed it, and Eleanor Roosevelt was arguably the most famous woman on earth for her globe-trotting good works until her death, 17 years after her husband’s, in 1962.

And they were blood relatives, to boot. The men, who were fifth cousins, turned the American presidency upside down, transforming it into a “Bully Pulpit” and the “Imperial Presidency” it largely remains today. When big things needed doing, these two men in the White House led the way, whether it was digging the Panama Canal and fighting monopolistic trusts or establishing much of today’s federal safety net and leading the nation to victory in World War II.

Teddy and Franklin, and Eleanor as well, talked directly to the American people by cultivating the press as none of their predecessors had – and in Eleanor’s case as none have since. Teddy adamantly believed (he did everything adamantly) that the American president should be dominant over the US Congress because he alone was elected by all of the American people – as opposed to those nattering provincials on Capitol Hill.

Eleanor, who was Teddy’s niece and her husband’s fifth cousin once removed, similarly turned the role of First Lady on its head, holding press conferences, speaking to the Democratic Convention, writing a popular newspaper column – among many other things that presidential wives had never contemplated much less attempted. Since women were not allowed at her husband’s press gatherings, she invited only women to hers. Eleanor was more than the sum of her feminist accomplishments, however: she was her husband’s liberal conscience, relentlessly advocating for policies that he sometimes shied away from because of political exigencies.

The Roosevelts: An Intimate History by Geoffrey Ward and Ken Burns, is a companion volume to an upcoming PBS series and is richly laden with images: from period photographs and editorial cartoons to reprints of letters and front page headlines. It is as much a photo album or scrap book as anything else, and at times the reader wishes that there was more room for biography. It sometimes flirts with being CliffsNotes.

Ward is an historian and author of 16 books, including a previous one on FDR. Burns is the noted producer and director of documentaries such as “The Civil War.” His foray into prose, in the preface, is a little blurry, but still discernible in describing the challenges of biography: “How can we seriously expect to know and fully comprehend three beings born more than a century before us? We can’t fully, of course, but we are nonetheless obliged to try, to find, in the free electrons their lives give off, signals that might prove helpful to our present.”

Subatomic particles aside, Burns and Ward have produced a fascinating, eminently readable, and well researched triple biography.

These three Roosevelts were different from you and me long before they rose to political prominence. Descended from a Dutch immigrant who arrived in New Amsterdam (soon to be New York City) circa 1640, they were raised to believe there was precious little that exceeded their grasp. Good schools, money, and well-heeled friends were a given. Who among us, after all, knows who our second cousins are, much less our fifth? Or takes a three-month honeymoon, as Franklin and Eleanor did? They charted their own course in life. Life wasn’t supposed to happen to such people. But it did.

For Teddy it was childhood asthma, which he overcame (and overcompensated for), not to mention the death of his young first wife and mother on the same day, in the same house, in 1884. In 1912 he continued giving a political speech while bleeding from a would-be assassin’s bullet.

For Franklin it was polio, which crippled him in 1921, the year after he had been the Democratic Party’s Vice Presidential candidate. He was 39 years old, and his political career was thought to be over.

For Eleanor it was a massively unhappy childhood: a drunken philandering father, who died when she was 10, and an unstintingly disapproving mother. Her marriage to Franklin was no picnic, either. Their five surviving children would embark on 19 marriages between them, a testament, perhaps, to familial optimism.

The subjects of this book were nothing if not optimistic. They believed they could do great things and they succeeded more often than not. And while the two branches of the family tree – Teddy’s Oyster Bay Republicans and Franklin’s Hyde Park Democrats – sometimes feuded, the two men from different parties were both dynamic proponents of progressive ideals, from workers’ rights to regulating the national economy to ensure a level playing field.

Whether it was Teddy’s “Square Deal” or Franklin’s “New Deal” or Eleanor’s various crusades, most Americans, especially the less affluent, believed that these three people, so different from them in so many ways, were on their side. This book pays well-deserved tribute to the three remarkable Roosevelts and makes a wonderful read, although readers looking for greater depth would be advised to supplement with other of the many excellent Roosevelt biographies already in print.

David Holahan is a regular Monitor contributor.