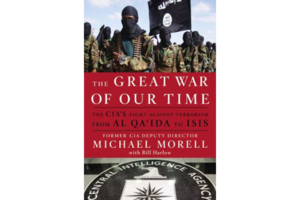

'The Great War of Our Times' offers an insider's view of the war on terror

Michael Morell, former Deputy Director of the CIA, presents a memoir that is both an eye-opener and a warning.

The Great War of Our Time:

The CIA's Fight Against Terrorism – From al Qa'ida to ISIS

By Michael Morell with Bill Harlow

Grand Central Publishing

384 pp.

The Great War of Our Time, a new memoir by Michael Morell, former Deputy Director of the CIA, offers a rich haul of gossipy insider details. We learn that George Tenet, the director of the CIA from 1997 to 2004, liked to sing Aretha Franklin hits and dribble a basketball down the hallways of the agency. We watch as Bush’s beloved dog, Barney, chews the tassels on Tenet’s loafers in the Oval Office. But the book also makes many strong and unsettling claims: that the Arab Spring helped Islamic extremism flourish, that the Edward Snowden revelations directly aided ISIS, that the use of enhanced interrogation techniques such as waterboarding yielded essential intelligence, and that the hijacking of a transatlantic flight remains well within the capacities of Al Qaeda.

Morell worked in the intelligence community for 33 years, but he won the important post of intelligence briefer for George Tenet in the late 1990s. The job demanded that he survey and synthesize massive quantities of intelligence that the CIA gathered from around the world and select which items to bring to the director’s attention. In 2000, he assumed the coveted position of daily briefer for George W. Bush. Six and often seven days a week, Morell delivered the PDB – President’s Daily Brief – in the Oval Office, or anywhere in the world Bush was traveling. Once again, he was charged with deciding what intelligence items merited the attention of an immensely powerful figure. The information he presented directly shaped the President’s worldview and informed his policy decisions.

Before 9/11, Morell rose at 3:30 a.m. every morning to prepare and polish the daily brief. After 9/11, he began waking at 12:30 a.m. to sift through the wave of threats inundating the CIA. In a candid assessment, Morell offers what some might consider an understatement, noting that Bush “did not have a particularly deep background in foreign affairs.” But Morell defends Bush against accusations that he dismissed and ignored ominous threat briefings in the months before 9/11. Because the intelligence did not contain specific and actionable information, he argues, there was not more that Bush could have done to prevent the attacks.

Morell is hardly the first to analyze the pre-9/11 failures of US intelligence agencies. He narrates the familiar story of the 1998 missile strike in Khost, Afghanistan, that almost killed Bin Laden, a near-miss that invites tantalizing speculation about possible alternate histories. He explains how bureaucratic infighting at the CIA hampered the efficacy of certain operations – analysts were not always taken as seriously as they should have been – and concedes that the CIA and FBI did not share vital information about the movements of the 9/11 hijackers. He also, unsurprisingly, defends the CIA, painting it as the victim of a broader indifference to terrorism and a subsequent lack of funding that characterized the political climate of the late 1990s.

It was 9/11, of course, that made counterterrorism a priority for the CIA and mobilized the political will to expand the agency’s budget and powers. On Saturday, Sept. 15, 2001, Morell remembers Bush dismissing the advice of a State Department official with the following words: “F**k diplomacy. We are going to war.” This was the spirit that led to the invasion of Iraq, although questionable intelligence about that country’s possession of Weapons of Mass Destruction was a more immediate catalyst. Dick Cheney and his staff look particularly bad in Morell’s account. Despite the fact that the CIA doubted and retracted certain intelligence sources indicating WMDs, Cheney and his aides continued to mention the dubious intelligence in public statements and exerted pressure on the CIA to support their political agenda of invading Iraq.

Morell staunchly defends the use of drone strikes and enhanced interrogation techniques that the military and the CIA deployed after 9/11. He claims that the number of women and children killed by drone strikes is vastly exaggerated and that the weapons are precise and effective means of targeting known terrorists. Unfortunately, however, his argument is undermined by the fact that he is unable to reveal classified data that would support his point. Absent such evidence, he’s basically asking his readers to trust him. He does give certain examples of terror plots that were foiled in part because of information extracted using EITs: a scheme to target the Brooklyn Bridge, for example. He also notes that some of the intelligence that led to the successful 2011 raid on Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, resulted from interrogation techniques that some have denounced as torture.

Whether such intelligence might have been obtained by other means is difficult to know. Morell’s position, once again, is essentially that we should trust him when he says that EITs were necessary to national security. But he does poke some persuasive holes in Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s report on torture, and he certainly establishes that the CIA was acting with the knowledge and approval of both the White House and the Senate, not simply operating as a rogue agency.

Some of the more startling claims in the book involve Edward Snowden, ISIS, and the Arab Spring. “Snowden has made the United States and our allies considerably less safe,” he writes. “I do not say this lightly: Americans may well die at the hands of terrorists because of Edward Snowden’s actions.” While he does not endorse the view that Snowden was an agent of Chinese or Russian intelligence agencies, Morell raises the possibility that Snowden underestimated the capacities of hostile foreign governments and was himself the victim of information thefts. After Snowden revealed specifics about the surveillance and collection methods used by the NSA, CIA, and other American intelligence agencies, ISIS and other terrorist organizations immediately began changing their tactics, using non-American email programs and encrypting communications that were previously a valuable source of intelligence. Foreign intelligence agencies in Iran and China have also adjusted their operational protocols after the Snowden revelations, according to Morell.

These changes roughly coincided with the series of revolutions in the Middle East known as the Arab Spring. Morell argues that Libya and Egypt are just two examples of a broader phenomenon: After a revolution topples a repressive ruler, the resulting power vacuum often allows Islamic extremism to flourish. Having dismantled the military capacities of former regimes, the new leaders should not be surprised when they lack the means to control their territories and stop the spread of ISIS.

Morell reveals many interesting details – some previously unknown – from his long career. He helped negotiate the release of four New York Times employees captured by Qadhafi’s forces in Libya in 2011. He was present during President Obama’s careful deliberations and intricate planning preceding the strike against Bin Laden in 2011. He also gives a thorough account of the Benghazi attack in 2012, offering a play-by-play of the attack itself and the political wrangling that ensued.

The fundamental argument of his book is that robust intelligence agencies are essential for national security and that support for them should thus transcend partisan feuding. He offers many chilling examples of narrowly averted terror attacks that could easily have caused mass casualties. He also mentions frightening future threats ranging from a weaponized strand of the bubonic plague to bombs that are surgically implanted inside the human body in order to escape detection. Al Qaeda’s desire to obtain a nuclear bomb represents another looming risk.

Though it’s clear that he wants to defend the reputation of the agency where he worked for so many years, Morell gains credibility by noticing the many weaknesses and flaws in the design and function of intelligence agencies. Ultimately he presents a persuasive and powerful case that without substantial financial and political investment in disrupting international terrorism, most of these future threats are not simply possible but inevitable.