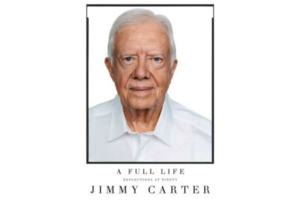

'A Full Life': Jimmy Carter writes again

At 90, Carter looks back on a remarkable life.

A Full Life:

Reflections at 90

By Jimmy Carter

Simon & Schuster

272 pp.

Although widely considered a sub par President – in the bottom half of virtually every ranking – Jimmy Carter is clearly a remarkable man. During his 90 years he has been an accomplished submariner, farmer, author, peacemaker, election monitor, philanthropist, carpenter, teacher, and public servant. He is a Nobel Peace Prize recipient and one of his many books was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. He is also a poet and a painter and examples of both arts appear in his latest memoir, A Full Life: Reflections at 90.

Love him or loath him, the former president is yet a force to be reckoned with. He has written more than 30 books and odds are he already is working on his next one. It’s hard to imagine Jimmy Carter taking a nap; but if he took a mind to, one would assume he’d be good at that, too.

While his latest opus inevitably resembles a greatest hits album, it does examine his life, career, and times in succinct and often telling fashion. The early chapters devoted to his formative years in Georgia, both before and after his 11-year career in the US Navy, are the most compelling.

Carter wasn’t born in a log cabin, but the family farmhouse in 1920s was rudimentary: no electricity or running water and heated with wood. He worked on the farm from an early age and showed an entrepreneurial spirit by producing bags of salted peanuts that he peddled in town. He was driving the family pickup around town at the age of 12.

Race was a complicated, sometimes subtle issue for a young boy in Plains, Ga., and Carter’s early playmates were the black children of the poor farm workers who lived nearby. When the son of a wealthy black neighbor returned from Harvard University to visit, Carter’s mother, Lillian, would welcome him in the front door, while the son noticed that his father “would quietly leave the house.”

The question of race could be less subtle, too. Lillian Carter was the county campaign coordinator in 1964 for Lyndon Johnson, who was strongly pressing for civil rights, and she found her car vandalized. When her son Jimmy refused to join the local White Citizen’s Council, and voted to integrate his church, and pressed for equal opportunities for black students as chairman of the country board of education, the only service station in town refused to sell his family gasoline. His children were harassed in school. Carter writes that Plains High School would not admit its first black student until 1967, 13 years after the US Supreme Court unanimously struck down “separate but equal.”

The author takes the reader on an engaging personal journey through the later half of the 20th century, as he saw it. From his submarine off China in 1949 he could spot the campfires of Mao Tse-tung’s army, which was poised to take over the entire mainland. He was president when the Three Mile Island nuclear accident occurred in 1979, and he insists the media overplayed it. When he ran against President Gerald Ford in 1976 and Ronald Reagan in 1980, his campaign spent about $50 million total for both races using only allotted public funds; his opponents did likewise. In 2012 alone, the Obama and Romney campaigns raised more than a $1billion apiece from private sources with which to savage one another, never mind the more than $500 million spent by “independent” superPacs.

In 1979, Carter’s intensifying feud with Senator Ted Kennedy torpedoed his health care initiative, which the author touts as more comprehensive than Obamacare. A bitter primary fight with Kennedy along with the ongoing Iranian hostage crisis opened the door for Ronald Regan to defeat Carter in 1980.

In a rare mea culpa, the author writes, “A serious political mistake was not being more attentive to the Democratic Party, both in preparing it for the 1980 election and in avoiding the schism between my supporters and those of Senator Ted Kennedy. I should have made a better effort to maintain the cooperation that he and I enjoyed during my early months in the White House.”

In the spirit of bipartisanship, Carter also has experienced bumpy relationships with others, among them Presidents Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama. The advice of a gadfly, even a prominent one who is often on the right side of history, is not always welcome at the White House. The author is not shy about pointing out instances when he believes he was right and others wrong.

Besides chronicling the grand sweep of world events in prose, Carter sometimes addresses more personal matters in poems that are sprinkled throughout the book. One of them offers a clue as to what may have driven the author to strive to be the best in virtually everything he has attempted in life. This is a man, after all, who as president managed to run 40 miles a week and always wanted to beat his personal best, to the point of heat exhaustion in one race.

In a poem about his father, he writes “even now I feel inside the hunger for his outstretched hand, a man’s embrace to take me in, the need for a word of praise.” Like a true Christian, Carter loves his father, warts and all.