'Destiny and Power' brings a gentle touch to biography of Bush 41

Jon Meacham offers a surprisingly deferential biography of George Herbert Walker Bush.

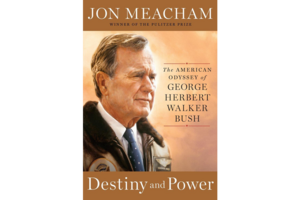

Destiny and Power:

The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush

By Jon Meacham

Random House

864 pp.

Jon Meacham, whose biography of Thomas Jefferson was a bestseller and whose biography of Andrew Jackson won the Pulitzer Prize, has chosen for his new subject a figure from recent, living memory, the country's 41st president, George Herbert Walker Bush, with whom Meacham spoke often at the family residences at Kennebunkport, Me., and Houston. In his author's note, he writes, “My first and greatest thanks are due to George H. W. Bush, who granted me access to his diaries and sat (usually patiently, and always politely) for interviews from 2006 to 2015.” And in his acknowledgments only two pages later, he repeats, “As noted earlier, I am most grateful to George H. W. Bush and to Barbara Bush, whose cooperation and patience made this project possible.”

This is deeply troubling, of course. A biographer who chronicles a living person is already at risk of being suspected of spin or bias; a biographer who repeatedly thanks his subject for being patient with him can legitimately be suspected of worse things. Meacham's books on Jackson and Jefferson were notable for their judicious marshaling of source material, but the subjects of those books were long gone. Destiny and Power is about a man who was President less than 30 years ago, the patriarch of the one of most powerful political families in current American history. It can change the whole dynamic of the biographer's art, although it shouldn't.

Bush's early life, his birth in Massachusetts, his youth in Greenwich, Conn., and Kennebunkport, his Navy pilot service in the Pacific during World War II, his rocky early campaigns to enter public life … all are narrated with Meacham's customary energy. And of Bush's 12 years at the heart of American political power, Meacham is right to point out that there were genuine triumphs: “As president of the United States he had ended the Cold War with the Soviet Union, lifting the specter of nuclear war from the life of the nation and the world, and led a global coalition to military victory in the Middle East.” But at the same time the economy entered a recession, and President Bush was lampooned in the press as hopelessly out of touch with ordinary Americans. “The caricature wasn't particularly fair,” Meacham writes, “but, as Bush often said, politics never was.”

The clear implication here is that Meacham himself is striving to be fair, but looking at his handling of even a couple of key incidents in the GHW Bush story raises serious doubts.

Take, for instance, the 1981 assassination attempt on President Reagan by a young man named John Hinckley. On the evening of the attempt, Bush's son Neil had been scheduled to have dinner with Hinckley's brother Scott. To put it mildly, this is something that warrants Meacham's scrutiny, and he fails his readers completely. Not only does he base his brief account entirely on "When Things Went Right," the 2013 memoir of long-time Bush aide Chase Untermeyer – a distant bystander with no special knowledge – but its astonishingly blasé conclusion, “An hour passed before it became clear that there was nothing more to the story than remarkable coincidence,” isn't sourced at all. “Remarkable coincidence” seems to be Meacham's opinion, and even if it isn't, it's still only Untermeyer's.

Or take the notorious arms-for-hostages deal the Reagan White House made with Iran in 1986. Vice President Bush at first adamantly denied any knowledge of the deal and then equivocated about its nature. To his credit, Meacham maintains that record is clear: Bush knew what was happening. “[He] was an old spymaster and a realist,” he goes on to write, “That his first impulse was to hide the truth, however, and that he continued to maintain, on occasion, that the deal was not about arms for hostages but was, rather, 'strategic,' was unworthy of his essential character.”

Unworthy of his essential character … or indicative of his essential character? After a few too many watercress luncheons at Kennebunkport, it's possible Meacham gets the two confused.

The most depressing part of this long hagiography is the way Meacham attempts to weasel out of accountability for these or any other willful credulities on his part. He insists that despite its exhaustive notes and bibliography, his book isn't “a full life-and-times” but rather a “biographical portrait.” He knows that many of his readers were alive during the Bush years, and he allows “there will doubtless be those who will argue with the exclusion of this episode or that issue with my choice of narrative emphasis.”

This episode, that episode … such wording poises everything on the very brink of blanket amnesty, and such is clearly the goal of "Destiny and Power," which wafts of noblesse oblige on every page. Many Americans will remember a different President Bush – more venal, more conniving, but also more interesting – and they'll wish Meacham had written a biography of that man, warts and all.