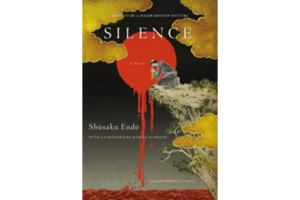

'Silence' is being re-released in English translation in advance of a 2016 film adaptation by Martin Scorsese

Japanese novelist Shūsaku Endō explores themes of life, death, and moral value in a searching and disquieting novel.

Silence

by Shusaku Endo (Author), William Johnston (Translator)

Taplinger Publishing Company

201 pp.

One of the 20th century’s most famous thought experiments goes something like this: Suppose that a runaway trolley is bearing down on five people who are tied to the tracks directly in its path. By pulling a lever you can divert the trolley onto a sidetrack and save five lives, but this will kill a single unsuspecting person. Should you pull the lever?

Posed in many permutations, the so-called “trolley problem” has been debated by moral philosophers, psychologists, neuroscientists, countless undergraduates, and, most recently, advocates and opponents of self-driving cars. Most people – roughly 90% in one survey – agree in theory with the moral calculus of sacrificing one person to save five. But if respondents imagine that the one person who will die is someone they know and love, the percentage who think they would still be able to pull the lever drops dramatically. As soon as a tendril of the actual reaches into the sanitized abstraction of the hypothetical, moral clarity gives way to something murkier.

In 1966, one year before a British philosopher first articulated the trolley problem, Japanese novelist Shūsaku Endō explored similar themes in a searching and disquieting novel called Silence. Set in the early 17th century, a period of intense persecution for Japanese Christians and European missionaries in Japan, the book recounts the physical and spiritual torment of a Portuguese priest who is captured during a clandestine mission to the island’s Christian communities. In advance of a 2016 film adaptation directed by Martin Scorsese, Picador has reissued the novel in an English translation by William Johnston.

The Basque missionary Francis Xavier first brought Christianity to Japan in 1549. The new religion flourished for a few generations, but by 1614 the Japanese government had issued an edict of expulsion that banished all foreign missionaries. By this point there were roughly 300,000 Japanese Christians out of a total of population of 20 million. Soon the Christian faith was outlawed. Government authorities raided suspected Christian communities in search of crucifixes, icons, or rosaries. Those who refused to trample on an image of Christ and call the Virgin Mary a whore were tortured until they renounced their faith or died.

The hero of Endō’s novel is a Portuguese priest named Sebastian Rodrigues. He and another priest slip secretly onto the island to minister to the underground Christian communities of Japanese peasant farmers near Nagasaki. Betrayal and torture are constant risks; the Japanese government will pay 300 pieces of silver to anyone who identifies a Christian priest.

The novel is a strange, powerful hybrid of political thriller and religious allegory. It has the suspense of nighttime raids, tenuous alliances, pursuit and capture, but the true drama is interior and spiritual. Father Rodrigues knows that he will almost certainly be betrayed and tortured at some point, but he aspires to emulate Christ by trusting even those who least merit trust. “It is easy enough to die for the good and beautiful,” Rodrigues writes in one of the letters that comprise the first section of the novel, “The hard thing is to die for the miserable and corrupt.”

He anticipates that his central struggle will be the choice between apostasy and an agonizing death by torture. But once the Japanese authorities apprehend Rodrigues, he discovers that they have devised a dilemma in some ways crueler than he imagined. He’s presented with a choice between two options: if he does not recant, three Christian peasants he has come to know will be hung upside down above a pit of human excrement until they die. If he does recant, they will be spared.

The resemblance to the trolley problems emerges as Rodrigues’s interior monologue makes one thing clear: to renounce the Christian faith would be a kind of death. It would cause disgrace in the eyes of the church and the extinction of his entire identity. Yet he can’t help but notice that to renounce Christianity would also be in some sense be the most Christian course of action. It would stop the suffering of the three peasants and save their lives.

Christian faith charges the ethics of the trolley problem with several interesting currents. To the extent that a given bystander has internalized the Christian injunction to love all men as brothers, the distinction between the deaths of strangers and the deaths of loved ones vanishes. Belief in the afterlife, however, might also change the calculation. If blissful eternal life awaits the martyred, perhaps the imperative to avert their deaths diminishes.

Endō realizes what Milton and Dostoevsky also knew – that doubt makes for more interesting literature than blind faith. “If he does not exist,” Rodrigues reflects about God, “how absurd the whole thing becomes.” The novel discovers in the anguished ruminations of Rodrigues something that transcends particular religions: what it feels like to engage in complex moral reasoning about matters of life and death. Once the austere abstractions of a philosophical thought experiment become complicated by an infinity of specific human considerations, confidence in a clear right answer begins to seem more a matter of faith than reason.