'Nemesis' tells how a single drug lord came to rule Rio

Misha Glenny digs deep below the surface to tell a dark but riveting story.

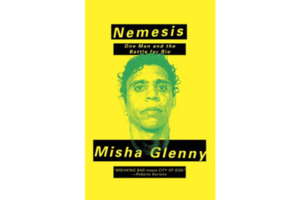

Nemesis:

One Man and the Battle for Rio

By Misha Glenny

Knopf Doubleday

320 pp.

In Rio de Janeiro, in the 1980s, all the rotten eggs were gathered into one basket: the absence of state authority; fractious, corrupt, and vicious federal, military, and civil police; fractious and vicious gangs; poverty and plenty living huggermugger; and the alchemy of turning the coca leaf into cabbage – that is, money. Big money, absurd amounts of money, in a city undone by greed and need.

It was the perfect storm, and Rio came in for a serious pulping. In Rio, in the interregnums between storms, it was only the recognized command of a don, lord of gang or drug, that kept the city from imploding. This man possessed “reputation within the community; acceptability to the local police; and authority within his organisation.”

His capacity for violence was implied, displayed only for tactical purposes, to shock and awe; he cultivated respect and loyalty through episodes of magnanimity and the ability to protect; he lived among the people, distributing breadbaskets and frontier justice; he kept the books and knew who was a friend. He was ghostly, everywhere at once and seemingly omniscient. He didn’t brook disobedience. He was Marshall Tito. He was the Taliban.

His name is Antônio Francisco Bonfim Lopes. But you can call him Nemesis, everyone else does, and he was the don of Rocinha, the largest of Rio’s slums, known as favelas. He is also the protagonist of Misha Glenny’s fine book, the grim, elucidating Nemesis: One Man and the Battle for Rio.

Glenny makes a habit of exploring milieus you wouldn’t want your sister running in – international organized crime, the darkest corners of the Internet – though the favelas of Rio are atypical, complicated slums with an ace up their sleeve: proximity to wealth. Thanks to Rio’s hilly topography and history of settlement, the city’s many favelas are situated shoulder to shoulder with both middle-class neighborhoods and the swankiest of the swank. This plays to the favelas’ advantage, from nearby menial jobs to customers for the slums’ illegal goods.

The shanties may be as gaily painted as one of the Cinque Terre on the Ligurian coast, but, as Glenny points out, this ain’t Vienna. The sewers are open, the schools are closed, malnutrition and disease flourish, the alleyways are as crooked as the streets of old Boston – “little capillaries that led away from the main road into Rocinha’s dense, dark forest of dwellings” – and under the (benign or ferocious) dictatorship of Rio’s three main gangs: the Red Command, the Pure Third Command, and the Amigos dos Amigos.

“Nemesis” is the story of Nemesis, how he fit and flourished in the surrounding circumstances of his city, as told to Glenny during 29 hours of interviews with Nemesis at his home since 2011, the remote maximum-security facility Campo Grande. To tell this story, Glenny became a student of the country; he learned Portuguese and spent years interviewing Brazilians of all stripes. What he draws is a portrait: broad strokes, detailed coloration, overpainting when new material comes to light. For all the tale’s vileness, it is very skilfully told and a very strong piece of journalism.

Lopes was born not to the manor, but to a system that turns your poor workingman into a gangster. When his daughter fell deathly ill and he hadn’t the money to pay for her medicine, he took his troubles to the reigning don. The don loaned Lopes the money and said he could pay it off by doing occasional security work. This is how dons stay in power and lives change. Lopes’s eventual morphing into Nemesis is never certain and is full of as many pinch points and changes of direction as Rocinha’s back alleys, but Glenny deftly follows in his footsteps. Nemesis’s rise is fraught and gripping – he’s crafty and disquieting, but an unexpectedly delicate, teetering creature – and it was no cakewalk to trace his course. A hand to Glenny, then, who sometimes put his life on the line to get the story.

Glenny gives additional authentic heft to the book by dissecting the elemental nature of Rio’s drug world. Brazil in general was the obvious course for cocaine from Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Paraguay to points in Europe and West Africa. Rio not only had a major port directly to the south, but also a ready market: Thanks to geography, the favelas’ next-door neighbors had the cash to buy this fashionable, and expensive, new drug.

Widening the horizon, Glenny engages the whole War on Drugs, “which, were it part of a private sector strategy, would have been discarded decades ago as disastrously counterproductive.”

Besides the ever-popular Kalashnikovs, the weapons of choice for traffickers are Connecticut’s very own Rugers (an industry leader of the 2,288 makers of civilian firearms in the United States) and Colt AR-15s (lightweight, magazine-fed, air-cooled). The guns cost around $4,500 in Brazil, “so while Brazilian drug traffickers were making a healthy profit from selling cocaine ... American firearms dealers were getting a good chunk of the cash back.” It is a murderous cycle fueled by “the coke habits of middle classes from Berlin to Los Angeles.”

Nemesis’s fall was precipitous. Times changed if the products didn’t. New forces emerged in Brazilian society, a seismic shift in politics, resource exploitation, and the military occupation of urban terrain.

The recalibrations were too much for Nemesis. His world spun out of control. His family was in danger. He was, understandably, stressed and paranoid. He played a dangerous game of negotiation and prevarication with the police. He made a run for it and got nabbed, but not killed, as were his predecessors.

Which leaves the door open. In the end, was Nemesis the spider or the fly?

Peter Lewis regularly reviews books for The Christian Science Monitor.