'Raoul Wallenberg' tells the story of the bureaucrat who fooled the Nazis

Wallenberg, Swedish envoy and humanitarian, saved thousands of Jews during the Holocaust.

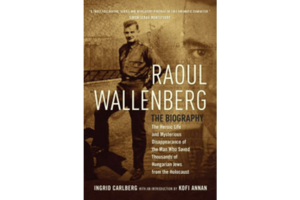

Raoul Wallenberg:

The Heroic Life and Mysterious Disappearance of the Man Who Saved Thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust

By Ingrid Carlberg (translated from the Swedish by Ebba Segerberg)

Quercus

640 pp.

There's a moment at the half-way point in Raoul Wallenberg, Ingrid Carlberg's 2015 biography (now out from Quercus in an English-language translation by Ebba Segerberg) of the Swedish envoy and humanitarian: Thousands of Hungarian Jews have been assembled at Budapest's Jozsesfvaros train station in 1944 so that they can be crammed into boxcars for transport to Poland, to the infamous concentration camp of Auschwitz. Every adult on those train platforms knew that almost certain death awaited them at the end of that journey – they knew what boarding those boxcars meant, for themselves and their families. And yet the orders had been given, the doors loomed, and there seemed to be no hope.

But in the moment Carlberg describes, hope suddenly arrives – not wearing bright armor or riding a tank, but unobtrusively, from the rear. A 30-year-old man, balding and dressed like a civil servant, elbows his way to the front of the crowds waiting to board the boxcars and begins addressing individuals seemingly at random. “You there, I have your name. Where is your document?” According to Carlberg, “bewildered men reached into their pockets and held out letters of any kind.” At which point the young man would say, “Excellent. Next!” Under the very eyes of patrolling Nazi and Hungarian fascist guards, the man was able to save some 500 people that day, out of the 17,000 waiting to be transported. No fisticuffs, no histrionics … just “effective and accurate bureaucracy” combined with a cool, almost incomprehensible bravery.

The young man was Raoul Wallenberg, who in 1944 was Sweden's special envoy to Budapest, and the heart of Carlberg's book is full of similar stories, in which Wallenberg uses a mixture of bureaucratic guile and courageous bluffing to save thousands of Jews from expatriation and death at the hands of the Nazis and their Hungarian quislings. Carlberg's life of the man is the most complete and winningly empathetic yet to appear in English, an absorbing portrait of an ordinary man who rose to the occasion of doing extraordinary things.

In March of 1944, Obersturmbannfuhrer Adolf Eichmann had been given orders from SS leader Heinrich Himmler to go to Hungary and “comb the country for Jews, from east to west, and, as soon as possible, deport each and every Jew to Auschwitz.” The country had held out for years in an uneasy alliance with Hitler's Germany, but the new government wanted no more foot-dragging when it came to rooting out and removing Hungary's Jewish population.

But by 1944, certain awkward niceties were in play. “In March 1944, it was no longer news to the Allies that the Nazi regime was transporting the Jews of Europe to concentration camps in order to exterminate them,” Carlberg writes. The world was watching now, and so the Nazis were minimally, grudgingly accepting Swiss neutrality in its Budapest legation.

Wallenberg and his colleagues immediately set about exploiting that tense detente for all it was worth. They created a registry of Hungarian Jews being issued special protective passports (the passports had no actual force of law, but they looked official enough to fool the paperwork-worshipping Nazis) and worked to provide those desperate Jews with food and shelter until their safe passage out of the country could be arranged. According to Calberg, the Nazis' “evil equation” amounted to allowing a few thousand “Swiss” Jews to escape as long as the remaining 200,000 could be processed for extermination.

Years spent making business trips to Nazi Germany and occupied France served to familiarize Wallenberg with the intimate power of fascist bureaucracy, and when the time came, he was able to use that very power to manipulate its own bloodthirsty creators. Calberg's biography is rich in details and witness recollections of Wallenberg's entire brief life, but the moral center of the book are its two virtuoso chapters, “Save As Many as Possible” and “Thirty-One Houses and Ten Thousand Bellies to Fill;” the core of the story is an understated valor that saved many thousands of people from Auschwitz.

Wallenberg spent those tense months impatiently waiting for the advancing Russian Red Army to break the Nazi hold on Budapest, which of course adds a bitter irony to the coda of his story. In January of 1945 he was summoned to the headquarters of Soviet General Malinovski on possible charges of being involved in spying for the Americans. He entered the labyrinth of the Russian incarceration state, and although rumors and sightings persisted for years, he was never seen by his friends in the free world again.

Calberg's biography stands as one of the most eloquent of the many thousands of tributes large and small that have been paid to the memory of Raoul Wallenberg since his disappearance. Among those tributes should have been a medal, a parade, and a peaceful old age, but courage wisely never counts on those things.