'American Rhapsody' is a dazzling slice of American cultural history

From Edith Wharton to Nina Simone, New Yorker writer Claudia Roth Pierpont brings 20th-century America alive.

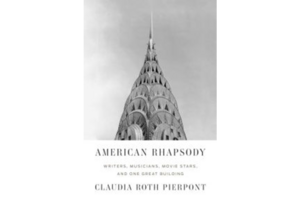

American Rhapsody:

Writers, Musicians, Movie Stars and One Great Building

By Claudia Roth Pierpont

Farrar, Straus & Giroux

320 pp.

I’m not quite sold on Claudia Roth Pierpont’s implicit description of American Rhapsody, her collection of her New Yorker articles as a prose rhapsody, “a sequence of distinctive parts, not as formally structured as a symphony but held together … by recurring themes.” And given that Gershwin’s working title for “Rhapsody in Blue” was “American Rhapsody” (as she admits she knows), the implied comparison is ludicrous if not outrageous, and I doubt the author herself believes it. But it doesn’t matter: This collection of profiles constitutes a fascinating (albeit narrowly focused) little cultural history of America during the last century. Pierpont writes about figures ranging from Edith Wharton to Nina Simone with sensitivity and erudition – and always in dazzling prose.

Much of the value of this book lies in Pierpont’s discussion of figures who are little more than names even to well read Americans, or who are completely unknown except to aficionados and academic specialists. Everyone knows the name Orson Welles but most know nothing about who he was or what he did other than “Citizen Kane” and “The War of the Worlds” broadcast. In “Rhapsody” we learn about his artistically brilliant but commercially disastrous work as a director of Shakespeare. Many of us associate the name Guggenheim with art, but know nothing about Peggy Guggenheim, the tormented heiress with an uncanny eye for brilliance whose collections established the canon of 20th-century American painting. And who even knows the names Bert Williams and Stepin Fetchit? The latter two were both gifted African-American performers who today are considered embarrassing reminders of the age of minstrel shows, but they paved the way for performers such as Dick Gregory and Flip Wilson.

Other profiles add nuance to our knowledge of well known figures. We tend to think of Edith Wharton at her literary zenith, not the anachronism she was in the 1920s, bored by the “schoolboy pornography” of Lawrence and Joyce. And what are we to make of the explicit and shockingly rapturous incest scene found among her notes for an unfinished short story? Wharton culled her papers so thoroughly it would not have survived unless she intended it to be found. And I’ve never read anything about F. Scott Fitzgerald that so brutally conveys the humiliations and miseries that plagued him throughout his life, or that so clearly enhanced my grasp of the seemingly and misleadingly accessible Gatsby. Pierpont’s account of how the teenage Katherine Hepburn was the first person to find her brother’s body after his suicide will forever change how you experience her performances.

As my reference to Gatsby suggests, Pierpont’s gifts as a cultural critic are on full display. Whether she’s writing about the varying quality of James Baldwin’s fiction, Gershwin’s musical influences, or the emotional range of Nina Simone’s singing, her mastery of her material is evident.

Pierpont’s subjects are made all the more compelling by her writing. Her account of the world premiere of “Rhapsody in Blue” made me happy for an afternoon. Her summation of the alcohol-wrecked career of Dashiell Hammett is heartbreaking: “For a few short years Hammet turned out a few short books that have yielded a chorus of voices and a phantasmagoria of beloved images ... before the gift just went – like a fist when you open your hand.” And her assessment of the Macbeth of Orson Welles is stunningly evocative: “embarrassingly bad but undeniably powerful. The viewer may laugh, but nervously: Macbeth is unrelenting – one long intensifying shriek.”

The author also takes full advantage of the quotability of her subjects. Who could resist repeating Edith Wharton’s remark after meeting Henry James for the first time, “He talks more lucidly than he writes, thank God”? Or Peggy Guggenheim’s response to the question of how many husbands she had had: “Do you mean my own, or other people’s?”

In spite of all the foregoing praise, “American Rhapsody” isn’t perfect: an essay on the Chrysler Building is simply out of place in this collection. And her profile of Orson Welles is actually a joint profile of Welles and Laurence Olivier. It would have been better in keeping with the stated American theme of this book to have left out Olivier and devoted more space to Welles.

But those are relatively minor quibbles. “American Rhapsody” is compulsively readable and fascinatingly informative. Learning this much has almost never been so much fun.