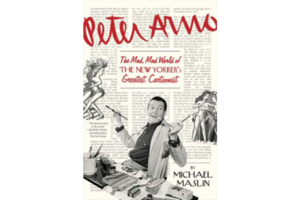

'Peter Arno' celebrates the iconic, one-of-a-kind New Yorker cartoonist

In Michael Maslin’s dazzling, well-illustrated biography, Arno’s story is told with skill and flair.

Peter Arno:

The Mad, Mad World of The New Yorker’s Greatest Cartoonist

By Michael Maslin

Regan Arts

320 pp.

“Cartoonist” is unlikely to be counted among professions promising excitement or adventure. After all, those who earn their keep with pen and ink spend most days stationed at a drawing board. Cartoonists may document the passing parade – the rise and fall of politicians or the ebb and flow of cultural trends – but they seldom partake of it. Instead, they contend with such humdrum matters as the burden of deadlines and the instructions of editors.

Yet the life and work of Peter Arno (1904-1968), whose cartoons ran in The New Yorkerfor more than four decades, counters this image. He entered the world as Curtis Arnoux Peters Jr., the offspring of a New York judge father and an English émigré mother. He received his schooling at the tony Hotchkiss School and, later, Yale University (from which he dropped out). And he was surely the only cartoonist who can be said to have starred on stage in a John Van Druten play (“Most of The Game”) and appeared on screen in a Jack Benny comedy (“Artists and Models”). Did we mention that he came up with the design of an automobile and was arrested for threatening a doorman at the Drake Hotel?

In Michael Maslin’s dazzling, well-illustrated biography, Peter Arno, Arno’s story is told with skill and flair. The author also makes clear that the cartoonist was regarded as sui generis by many of his colleagues, superiors, and successors. “Peter Arno tricked me into thinking that if you were a New Yorker cartoonist, you were King of New York,” said cartoonist Robert Leighton, who began contributing to the magazine long after Arno’s death. “It’s all based on one photo I saw of him in top hat and tails, probably with a showgal on each arm, walking down a New York street in the ’40s.”

Of course, even if Leighton had not viewed that photo, he would have had a sense of Arno’s orbit from looking through back issues of The New Yorker. Befitting his background, the cartoonist fixed his gaze on the flaws and foibles of the upper class. As Maslin recounts, Arno’s drawings depicted “husbands and wives’ cat-and-mouse games, and husbands and lovers, and wives and lovers,” as well as “the battleship grande dames, the sugar daddies, the precocious young, and clueless elders.”

In one representative cartoon (included in the 1979 Harper & Row collection entitled “Peter Arno”), a bedraggled, belligerent, bow-tie-wearing gentleman has been arrested and is seen standing in a police station among a swarm of officers, one of whom introduces him as “Mr. J. Stanhope Alderson.” “He has money, position, many influential friends, and we can’t do this to him,” the cop explains, recapping, with a smile, the arrestee’s protestations. In another cartoon from the same book, a bright-eyed bride sits with her groom in a car pulling away from the church in which they have just been married. It seems that some of their vows have made a greater impression on her than the others. “Just when do I get endowed with all thy worldly goods?” she asks, eagerly.

Arno’s artwork is endlessly expressive, communicating intricacies of character with sharp, simple lines. Consider the arch of a woman’s back as she leans through a doorway to survey a gaggle of gifts or the upright posture of a pair of elderly operagoers, one of whom has failed to properly operate his hearing aid (“You have so got it turned off!”) Even small details delight, such as the light cast by a television set being watched by quarreling marrieds or the white dabs of snow surrounding a couple huddled in the woods or the outstretched arms of a wife reaching for her husband’s “consumers’ research bulletins.”

In fact, this book’s succession of wild real-life incidents suggests material for a potential Arno cartoon (the captions to which were frequently furnished by others, according to Maslin). In 1929, Arno brought a lawsuit against the Packard Motor Company, charging that the car he bought “couldn’t reach the 90-100 miles per hour as advertised.” (A decade later, when Arno designed a car for the Albatross Motor Car Company, the resulting vehicle was touted for its “beauty and overall aesthetic appeal” rather than its speed per se.)

And in 1938, while married to the second of his two wives, Arno was seen holding hands with none other than Brenda Diana Duff Frazier, famously described by Lifemagazine that same year as “the outstanding debutante” for, among other qualities, “her long hair” and “her vivacity.” A biographer of Frazier is quoted as downplaying the relationship, speculating that Arno sought her company “just for publicity,” which hardly does credit to the man.

In other ways, however, Arno was unremarkable. The cartoonist’s work routine is thoroughly detailed here, with a New York Postreporter noting in 1939 that he stayed home most Mondays because his deadline at The New Yorker fell on Tuesdays: “He, therefore, leaves work until the last possible moment, works right straight through, smokes several packs of cigarettes and loves every moment of it.” And New Yorkereditor Harold Ross is quoted in a series of simultaneously exasperated and affectionate communiques concerning everything from Arno’s tardiness at delivering cartoons (“There are various rumors around the office as to whether you will or will not do any drawings in the near future”) to his requests for higher fees (“His price is $1000 a drawing, which he feels the company can pay at this time, and, in fairness, should pay”).

Even so, it is obvious that Arno was nonpareil. Writer Philip Hamburger remembered encountering him at a 1952 party celebrating the start of William Shawn’s editorship at The New Yorker. The cartoonist, Hamburger said, arrived with a flask full of martinis: “He was taking no chances on someone being stingy with the vermouth!” It is only surprising that the episode did not prompt an Arno panel.

Peter Tonguette has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard, National Review, and many other publications.

# # #