'Wolf Boys' offers a disturbing insider view of drug dealing

This eye-witness account of drug dealing on the US-Mexico border shocks but fails to address larger questions.

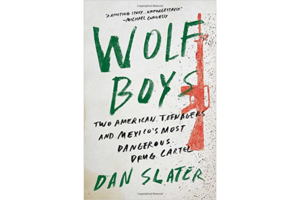

Wolf Boys:

Two American Teenagers and Mexico's Most Dangerous Drug Cartel

by Dan Slater

Simon & Schuster

352 pp.

Journalist Dan Slater’s new book, Wolf Boys: Two American Teenagers and Mexico’s Most Dangerous Drug Cartel, features the sort of ghoulish and graphic violence that many Americans encounter only in movies and television shows. The bodies of murdered enemies are burned to ashes in oil drums, people are beaten to death with shovels and forced to eat human brain, and a killer rips out the heart of a beheaded man with his bare hands.

Part of Slater’s purpose in the book is to show that Americans witness and commit these sorts of atrocities. His two teenage main characters work as cartel assassins in the border town of Laredo, Texas. Both are American. They rapidly graduate from stealing cars and selling firearms to executing targeted killings of drug-trade rivals. Laredo sits on the lucrative I-35 smuggling corridor, and the Sinaloa and Zeta cartels have warred for years on both sides of the border to control the area.

Slater succeeds in documenting some grievous individual and systemic failures. In one scene, a corrupt Laredo cop sells guns and grenade launchers from the trunk of his car. The cop even allows his clients – young teenagers – to flip through law enforcement catalogs and make their inventory selections. The non-corrupt majority of law enforcement appears largely powerless. One of the teenage assassins Slater profiles gets released from jail three times in six months, despite strong evidence linking him to multiple murders.

Millions of dollars and thousands of jobs depend on the prohibition of drugs. Slater gives a partial list of some of the legitimate professions: “Cops, agents, lawyers, judges, court workers, probation officers; not to mention diesel mechanics, truck yard owners, and warehouses that stored seized contraband for the government....” In the illegal economy, of course, an entire universe of jobs also exists. The mutual interdependence of these licit and illicit economies is just one of many indications of the problems that drug prohibition causes.

Slater makes only passing reference to the larger policy questions that his topic raises. He focuses instead on the human stories of those enmeshed in the criminal underworld that prohibition helps to create. These are sometimes vivid, but it would have strengthened his book to provide more substantive analysis on the politics, history, and economics of the American war on drugs, as "Chasing the Scream" by Johann Hari – an excellent recent book – did quite capably.

Slater’s telling of the stories of the boys themselves is also quite problematic. He exchanged hundreds of letters with one of the assassins who is now imprisoned. It is seldom clear, however, what if any of the material that Slater narrates has been independently confirmed by other sources. Relying too heavily on a single source, as journalist Gay Talese recently discovered, makes a narrative vulnerable to the exaggerations and deceptions of its main character.

Slater also makes painfully strained attempts to inhabit the point of view of his characters. Describing the moment when one of the teenage hitmen first met his girlfriend, Slater writes, “Her nose flared gamely at the nostril.” Did the adverb “gamely” flash through the character’s mind at that time? Did he recollect this later and tell Slater during an interview about the manner in which her nostril flared? These sorts of questions arise far too frequently.

The problem is not that he tries to render the inner monologues of characters; many successful works of narrative nonfiction do the same thing. But it’s sometimes jarringly unclear whose point of view Slater is adopting. He writes about the “endless, anxious making of the self” and describes the “rictus of woe” on a corpse. These appear to be his own flourishes, but they stand out awkwardly from the surrounding passages in which he adopts the diction and slang of the Texas-Mexico border.

The largest issue, however, is that Slater seems to share his subjects’ romantic and glamorous view of violence. He lingers luridly on the most sensational details and offers very little pushback to the self-mythologizing account that his imprisoned correspondent offers of his murders. It does not help his credibility when he confides in the final chapter that he and one of the assassin’s brothers did cocaine together.

At the sentencing of one of the young men, the judge lamented the fact that legend and romance now surround the culture of violent drug-trafficking cartels. The judge faulted the young man for buying into this mystique. But it’s a mystique that journalists, television, film, and popular culture have all helped to create. As Slater’s flawed book shows, even works that are ostensibly dedicated to dismantling this false glamour can in fact perpetuate it further.