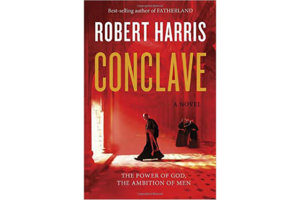

'Conclave' delves into the death of a pope and the process of replacing him

The author of the inventive thrillers 'An Officer and a Spy' and 'Pompeii' turns his talent for intrigue to the imagined inner workings of a papal election.

Conclave

By Robert Harris

Knopf

304 pp.

Robert Harris’s novels are wonderfully tart confections of political conspiracy, opportunism, cynicism, and vainglory. He has found his material in ancient Rome, France of the Dreyfus Affair, Bletchley Park, a (counter-factual) victorious Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, a rogue hedge fund, and the so-called War on Terror. Conclave, his 11th fictional engagement with high-stakes intrigue, goes straight for the mother lode: the Vatican.

It is 2018, and a pope who resembles the present one in humility, charity, and tolerance has died unexpectedly in his sleep. Cardinals from all over the world are assembling in Rome to choose his successor. The media are slavering, “reporters and photographers ... calling out to the cardinals, like tourists at a zoo trying to persuade the animals to come closer.” Armed guards, snipers, and surface-to-air missiles have been deployed against the threat of terrorist attack. Carpenters and technicians are preparing the Sistine Chapel for the electoral proceedings, and a number of cardinals begin to position themselves to step into the papal shoes. Factions and coalitions emerge in different permutations: progressive and reactionary parties, combining and splitting with the Italian, Third World, and North American contingents. Beneath it all, churning relentlessly, are the forces of what we may call the deep Curia.

We see events through the eyes of the dean of the College of Cardinals, Cardinal Romeli, an old, modest, and sincerely devout man whose “guilty recreation” is, appropriately enough as it turns out, reading detective fiction. It is his duty to officiate over the conclave and assure that it runs smoothly – which I’m happy to say it does not. A speedy election is desired lest it appear that the Church is falling into terminal discord. But perhaps it is. Romeli learns that, toward the end of his life, the late pope had lost his faith in the Church and, along with that shocker, had made some exceedingly strange decisions. On the very day of his death, he had met privately with one powerhouse cardinal, an aspirant to the papacy, and removed him from all his offices – then died before making the decision effective. What was that all about? And will this last act come out in the conclave? Furthermore, the old pontiff had also appointed a new cardinal whose existence had not been suspected until he arrives on the scene. What’s going on here?

Before unleashing the answers to these crucial question, Harris gives us a few splendidly satirical pictures of the workings of the Vatican, not least in the matter of ecclesiastical pelf. There is the American cardinal “who might come from New York and look like a Wall Street banker” but is not at all up to the job of straightening out the financial management of his department. As one old Italian cardinal remarks to Romeli, he would “never have given the job to an American. They are so innocent: they have no idea how bribery works.” We are also introduced to a dead ringer for the real Cardinal Bertone, whom the actual Pope Francis has censured for his extravagance in knocking together two Vatican apartments to create a vast luxury pad for himself.

As politicking commences and picks up heat, secrets from the past erupt to bury the candidacies of a couple of cardinals. Harris, the writer, loves the maneuverings and machinations of power-mongers, but he is just as superb here in showing men of true faith wrestling with the legitimacy of their own wishes and trying to fathom God’s will as events unfold. He goes so far as to suggest the presence of the Holy Spirit when Romeli discards a prepared homily to deliver an impromptu one of a completely different tenor before the assembled cardinals. It is a speech that sets the conclave on a most unexpected path.

I know this is all rather obscure – that’s the Vatican for you – but I don’t wish to reveal the plot elements that keep the book going against the countervailing force of Harris’s unremitting attention to rules of order and the arcana of ceremonial habiliments and accessories. Just when the story is getting a good head of suspense going, some matter of procedural housekeeping is explained in detail, or our old friend Cardinal Romeli starts putting on or taking off his choir dress, a great assemblage that includes scarlet cassock with 33 buttons (“one button for each year in Christ’s life”), cincture with tassel hanging midway up the left calf, rochet, mozzetta, zuchetta, pectoral cross, skull cap, and biretta.

Well before the end of the novel, it becomes clear where things are heading – even if certain details are a bit of a surprise. All in all, "Conclave" is not one of Harris’s best works; still, the political aspects of papal selection, the pressure of the “news cycle,” and the wheeling and dealing and backstabbing are excellently realized and put forward with a good deal of sardonic wit. This is where Harris excels and why one waits so impatiently for his next offering.