A trio of lovely new books about animals

From remarkable photos of animals to a gorgeous 'paper zoo' to Thoreau's accounts of his animal encounters, this spring offers a pack of excellent reads for animal lovers.

The Photo Ark:

One Man's Quest to Document the World's Animals

By Joel Sartore

National Geographic

400 pp.

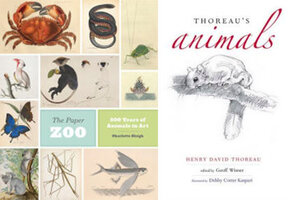

The Paper Zoo:

500 Years of Animals in Art

By Charlotte Sleigh

University of Chicago Press

256 pp.

Thoreau's Animals

By Henry David Thoreau

Edited by Geoff Wisner

Illustrated by Debby Cotter Kaspari

Yale University Press

280 pp.

“On the arm of a spiral galaxy, 93 million miles from the closest of the stars, spins the just-right, not-too-hot-or-cold, brown and green and water-blue sphere where all the living beings known in the universe dwell,” writes Douglas Chadwick in "We Earthlings," his wonderful introductory essay to The Photo Ark, a lavish new book of animal photos by Joel Sartore. “Pulsing, wriggling, sprouting, swimming, loping, fluorescing, swarming, mutating, flying, molting, yearning, branching, migrating, mating, and unfurling in a profusion of sizes, shapes, and hues and in numbers beyond counting, they turn the crusted skin of a molten-cored mineral orb fertile.”

That profusion of living beings has been the subject of countless books, and yet all those books combined only serve to scratch the surface of the profusion itself. Earth is host to roughly 30,000 species of fish, nearly 10,000 species of reptiles, another 10,000 species of birds, at least 300,000 species of plants, and, famously, 350,000 species of beetles alone – and this is only a small sample of the life-forms known to science. The real numbers are likely much higher.

National Geographic photographer Sartore's goal with his "Photo Ark" project is to capture clear, up-close photographs of as many of those animals as they exist in captivity. "The Photo Ark" selects over 400 from the more than 6000 such photos Sartore and his team have taken, and the result is one of the most visually arresting “coffee table books” in recent memory. Golden langurs and African wild dogs, an enormous American bison and a small, graceful sifaka, an African elephant and a Sulawesi stripe-faced fruit bat … all stare directly at Sartore's camera, and all are caught in a mesmerizing amount of detail, peering out from the alien realities of their separate worlds. Turning these pages actually does feel like up-close touring some kind of perfectly-realized ark or zoo.

Zoos are comparatively very modern inventions, historian Charlotte Sleigh reminds readers at the beginning of her own stunning animal-picture collection, The Paper Zoo, published in a beautiful oversized hardcover by the University of Chicago Press. For centuries, artistic representations of animals had to suffice as a substitute. “Animal pictures were, in their earliest days, expensive in their own right, but they were nevertheless more affordable than the real thing: a democractised zoo,” Sleigh writes.

The aesthetic breadth of the zoo she's assembled from the collections of the British Library is amazing. One every page, readers can discover a new marvel: John James Audubon's famous drawing of Icelandic falcons from his Birds of America; 18th-century drawings of elephant beetles; Francis Willughby's 1678 drawings of owls (one of the earliest attempts at visual classification); Edward Donovan's curiously atmospheric 1820 drawing of a small horseshoe bat flying over a ruined manor house; even a brightly-colored dodo from a book by Richard Owen who, we're told, “used underhanded means to make sure he acquired the first complete dodo remains to be recovered after the bird's extinction.”

Sleigh's big book contains hundreds of such enticing story-tidbits to accompany the gorgeous, endlessly-intriguing artwork she presents. The combination effectively recovers for the modern YouTube-watching audience something of the wonder these paintings and drawings must have brought to their original viewers, seeing these gloriously strange creatures for the first time.

And yet, one of the most remarkable animal-books of the season deals in nothing exotic at all. Editor and author (including for The Christian Science Monitor) Geoff Wisner follows up his 2016 book "Thoreau's Wildflowers" with an even more enchanting volume from Yale University Press: Thoreau's Animals, laid out along the same lines as its predecessor, with Wisner going through Thoreau's journals and presenting excerpts dealing with the everyday wildlife the great thinker and naturalist encountered in the forests and wetlands of Concord.

Wood frogs, yellow perch, dragon flies, moles, minks, bobolinks and dozens of other New England species cross his wandering path, and he never fails to notice. “Two red squirrels made an ado about or above me near the North River, hastily running from tree to tree, leaping from the extremity of one bough to that of the nearest in the next tree,” Thoreau writes on March 6, 1853, “... I approached and stood under this, while they made a great fuss about me.” “I see at a distance a kingbird or blackbird pursuing a crow – lower down the hill – like a satellite revolving around a black planet,” he writes on June 5, 1854. “I have come to this hill to see the sun go down – to recover sanity and put myself again in relation to Nature.”

Readers of "Thoreau's Animals," drawn in by Thoreau's masterfully insightful observations and helped considerably by the lovely drawings throughout done by Debby Cotter Kaspari, will find themselves in a similar mind frame, recovering their sanity as they turn these pages and putting themselves again in relation to Nature.