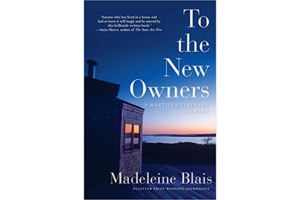

'To the New Owners' is a bittersweet ode to a Martha's Vineyard home

What happens when you sell a house you love this much?

To the New Owners:

A Martha's Vineyard Memoir

By Madeleine Blais

Atlantic Monthly Press

272 pp.

The title of journalist Madeleine Blais's new book, To the New Owners, refers to its melancholy main conceit: that these are the thoughts and reminiscences of a long-time Martha's Vineyard resident as she prepares to pull up stakes and put the rambling old family vacation house on the market. Here's a small hint of what you're getting when you buy this old place, the unspoken sentiment goes, with the equally unspoken but very loud follow-up: not that you'll appreciate it, barbarian gatecrashers that you are.

Anyone who's ever spent time on Martha's Vineyard – not the frenzy of a two-week vacation complete with astronomical rental fees and predictable family crises, but real time, measured in weeks or months, time spent not busily sightseeing but lazily lamenting sight-seers – will recognize the tone of Blais's conceit immediately; because the place is incredibly lovely and maybe even more so because it's an island, Martha's Vineyard has been prompting that same tone of gentle, melancholy regret since it was first named by Bartholomew Gosnold in 1602. Rumors that Gosnold wrote in his diary “Ye olde Island is now not what it once was, forsooth” may be apocryphal, but it's nevertheless true that for the last 400 years, the island's official motto might as well have been “There Goes the Neighborhood.”

Henry Beetle Hough, legendary publisher of the Vineyard Gazette (and a gentle presiding spirit over "To the New Owners," where the Gazette is mentioned as often as Holy Writ), made a 60-year career out of publishing books that looked back longingly to vanished versions of the place. “Now begins the story of the rise of Martha's Vineyard as a summer resort, and how the Island changed from its old ways of life and became as it is today,” he wrote – in 1936.

Blais therefore furthers a long tradition of writers trying to capture the special qualities of her time on the Vineyard, at the dilapidated “shack” that belonged to her husband's family. Located on Tisbury Great Pond, Thumb Point was “a funky place, very much a beach house, and a bit battered and worn – but very special.” The advice to temporary guests: “If you are in doubt about anything, err on the side of having fun.”

She first saw Thumb Point in 1976 and was struck by its improvisational nature: no electricity. Hand pump. Outdoor shower. But as she writes – in a sentiment that will be familiar to every long-time Vineyard visitor – it didn't take long to see the beauty of the place. “The world was in layers – the blue gray of the pond, the beige lip of sand in the distance, the different blue of the ocean, and yet another blue for the sky – an orgy of horizons, interrupted now and then by white birds, white foam, and white clouds.”

Most of the familiar places and names from standard Martha's Vineyard books are here in these pages as well: Peter Benchley and Jaws, visiting Clintons, Carly Simon, Walter Cronkite and the rest. The chapter on formidable Vineyard doyenne and Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham is the most charming in the book, positively luminous with nostalgic affection. And the broader canvas of Vineyard life – the shops, the storms, the wry local humor – is painted with exactly the kind of skill and evocation readers would expect from the author of the bestselling "In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle."

That broader Vineyard world can be notoriously cagey about accepting strangers. “It can take years of island living,” Blais writes, “to learn beyond which desultory dirt road lurks the world-class beach or to know who to call when the well goes dry and where to go to get the best bass bait.”

But while they're learning, she and her family are also having the times of their lives, celebrating, foraging fresh oysters and crabs from the pond, picking ticks off an endless crowd of rowdy dogs, and coming to love Thumb Point so deeply that it came to feel like a permanent part of their lives. “I almost convinced myself that all the years my family had spent in this spot, all the memories, good and bad, were a firewall against anyone else every occupying it,” she writes. “A dwelling that had meant so much to us could clearly never have the same meaning to anyone else.”

But her husband's family owned the old house, and family members get involved in other places, priorities change, and suddenly the absurd seller's market of Vineyard real estate starts to tempt. Thumb Point is packed up and sold. The beloved shack is torn down, and the new owners erect a 5000 square-foot mansion complete with, as Blais notes with a particular Vineyardesque shudder, a lap pool.

But the memories of that dear, battered old “shack” are still there to be savored by skillful writers waxing sentimental about how the Island changed from its old ways of life and became as it is today – a fact for which publishers thank their lucky stars.