'The Second Coming of the KKK' explores the largely forgotten 1920s resurgence of the Klan

The Klan was 'the biggest social movement of the early twentieth century,' one whose 'ideas echo again today,' writes New York University historian Linda Gordon in her startling new book.

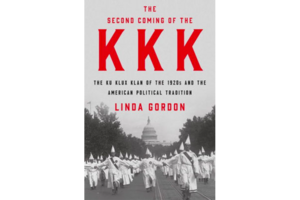

The Second Coming of the KKK

By Linda Gordon

Liveright

288 pp.

In the years after the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan rose from the bitterness and racism of the South to claim the mantle of American white supremacy. We think of this era when we picture hooded men on horses who burn crosses and lynch people.

But there's another KKK that's largely forgotten today, a national phenomenon in the Roaring Twenties that transformed Klan members and their allies into mayors, governors, and U.S. senators in states from Oregon and Colorado to Indiana and Maine.

Boosted by savvy marketing, shameless victimhood, and epic intolerance, the KKK even managed to tear the national Democratic Party apart, allowing the GOP to continue holding the White House.

The Klan was "the biggest social movement of the early twentieth century," one whose "ideas echo again today," writes New York University historian Linda Gordon in her startling new book The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition.

Inspired in part by the success of the 1915 racist hit film "The Birth of a Nation," an ode to the original KKK, founders of this new-and-unimproved Klan divided the nation into Americans and non-Americans.

They didn't get much traction until a marketing crew figured out they'd get more members if they hated more people. So the KKK transformed from its anti-black roots to focus more on the threats of other minorities whose mere existence supposedly threatened the American way – namely, Jews, Catholics, and immigrants.

The KKK accomplished its shocking rise through a veneer of polite respectability. If you looked at a 1920s-era newspaper in a city like San Diego, for example, you'd see notices for KKK meetings – "visiting klansmen welcome" – next to listings for the Shriners and the Knights of Columbus.

The Klan, clearly, was supposed to be just another fun social club with mysterious costumes, secret code words, and quirky rituals. Join the KKK, the pitch went, and you could network with local business types and meet new friends.

Indeed, opportunities for male bonding abounded. Hang out at the Klavern, burn a cross on a lawn, or drop by the big shindig at the park; one amazing photo in the book depicts KKK members – in robes and hoods – as they ride a ferris wheel at a Colorado picnic.

Women could be a part of the Klan too, with some embracing a kind of female empowerment that makes them an odd and perplexing footnote in the history of American feminism.

Fortunately, the KKK's heritage of deadly violence remained – mostly – a thing of the past in the North, Midwest, and West. But the Klan still relied heavily on intimidation and even tried to normalize vigilantism by partnering with local cops.

In fact, a reported 150 police officers in Portland, Ore. – now a progressive enclave – allied with the Klan. Gordon reveals other unexpected KKK hotspots where members controlled city governments or served as mayors: Southern California's Anaheim ("Klanaheim"), Dallas and Fort Worth, almost all cities in Colorado, and Portland, Me.

But it was Oregon, whose Portland had its own KKK mayor, where the Klan came perhaps the closest transforming its political influence into dramatic legalized bigotry.

As Gordon describes it, Oregon was perhaps the most racist state in the union outside the South, and KKK sympathy ran deep in the Beaver State. In a close election, Klan actually convinced state voters to support shutting down all private schools – every one – in order to kill off Catholic education. The Supreme Court unanimously threw the law out.

On a national level, the KKK was never more influential than in 1924, when a dramatic split in the Democratic Party over the Klan destroyed its hopes of retaking the presidency.

"The Second Coming" is a scholarly history with both the strengths and weaknesses of academic works. There's little in the way of storytelling, and the characters don't come alive on the page. Readers will need to look elsewhere for vivid portraits of heroes and villains in the KKK drama.

But Gordon is a thorough and perceptive historian, and she's careful to keep most of her opinions to herself: "I am less interested in condemnation than explanation."

She is willing, however, to link the KKK of the 1920s to today's American politics, especially the nationalist movement. But there's more to "The Second Coming" than grim déjà vu. There are lessons, too.

Liberals, for example, can learn from the 1920s critics who dismissed the KKK movement as "the inane hysteria of uneducated, lowbrow hicks," as Gordon puts it.

Yes, Klan members could seem a bunch of dingbats with their robes, rites, and goofy language of Klaziks, Kludds, Klonsuls, and, yes, a Kloran. In reality, condescension prevented the Klan's foes from understanding "how many other elites and intellectuals shared its worldview," Gordon contends. As she notes, it's quite possible that most Americans in the 1920s actually agreed with the Klan.

The KKK did not last. Hucksterism, hubris, and a bizarre murder scandal helped to spell its end as a significant force in much of the nation. Outside of spasms of violence and occasional stunts, the Klan remains largely irrelevant today.

Still, Gordon contends, "the Klannish spirit – fearful, angry, gullible to falsehoods, in thrall to demagogic leaders and abusive language, hostile to science and intellectuals, committed to the dream that everyone can be a success if they only try – lives on."