'The Betrayal of Mary, Queen of Scots' analyzes monarch's story from modern perspective

Mary’s story has been often told, but it has been interpreted differently through the generations.

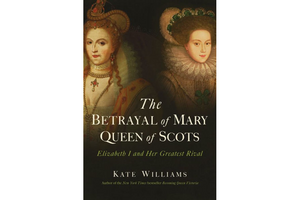

The Betrayal of Mary, Queen of Scots

By Kate Williams

Pegasus Books

416 pp.

In 1565, Mary, Queen of Scots wrote a letter to her cousin Elizabeth, queen of England, expressing her hopes for their relationship: “How much better were it that we being two queens so near of kin, neighbors and living in one Isle, should be friends and live together like sisters, than by strange means divide ourselves to the hurt of us both.” Elizabeth, of course, would sign Mary’s death warrant more than two decades later, leading to the beheading of the Scottish queen. Kate Williams expertly and entertainingly details the twisty and sordid path to the monarch’s execution in “The Betrayal of Mary, Queen of Scots: Elizabeth I and Her Greatest Rival.”

Mary, queen of Scotland from infancy following the death of her father, King James V, was essentially a pawn from birth. She was sent to France at age 5 after her mother arranged a marriage to the son of the French king, Henry II. The Scots hoped the alliance would protect their country from English aggression. For his part, Henry II hoped to use Mary to stake a claim to the English throne, as the child’s paternal grandmother, Margaret Tudor, was the sister of the English king, Henry VIII.

The 15-year-old Mary, strikingly beautiful and nearly six feet tall, married the 14-year-old dauphin Francis in 1558; King Henry II died the following year, making Mary queen of both France and Scotland. But when Francis died in 1560, Mary lost the French throne and returned to Scotland, a country she didn’t remember and whose power-hungry and warring nobles preferred to run things without her. The Scottish court, writes Williams, who serves as CNN’s royal historian and has authored previous books on Elizabeth, Queen Victoria, and Josephine Bonaparte, “was a place where masculine power was fighting to be resurgent. Mary was surrounded by men. And they were all fighting for control, using her to get power in whichever way they could.”

Elizabeth I, meanwhile, was crowned in 1559. She was the daughter of Henry VIII and the unfortunate Anne Boleyn, whose marriage to the king had been annulled before her beheading, making Elizabeth technically illegitimate. The Protestant queen felt her reign was shaky, especially as she refused to marry and produce an heir. She and her chief advisor, the cunning William Cecil, feared that a claim by the Catholic Mary would have the support of the country’s Catholics, particularly once Mary gave birth to a son, James, with her second husband, Lord Darnley. Williams makes the point, however, that James’s birth "both strengthened and weakened" Mary because "a boy, even one who couldn’t yet lift his head, was worth more than a woman." Mary too was at risk of being deposed.

The assassination of the corrupt and despised Darnley, planned by scheming nobles, set in motion the events that would culminate in Mary’s tragic demise. Readers unfamiliar with this famous episode of history will find the events shocking. The nobles who conspired against Darnley, hoping to get rid of Mary too, attempted to implicate the queen in his murder. The likely mastermind of the murder, the Earl of Bothwell, abducted Mary, raped her, and forced her to marry him, in what Williams calls “the most scandalous marriage in royal history.” Mary was subsequently seized and imprisoned by a rival faction of lords, who forced her to abdicate so James could ascend the throne. Because the new king was only 13 months old, the nobles would in effect be in charge.

While England wasn’t as lawless as Scotland, Elizabeth was always aware that women’s rule was tenuous and that what happened to Mary posed risks to her own power. In Williams’s words, “if an anointed queen could be abducted, raped, imprisoned and then deposed and no one protested, then what of the right of any queen to be on the throne?” Mary escaped her captors, but her fatal mistake was in overestimating Elizabeth’s sympathies and fleeing to England. She was desperate to meet with the queen, who she assumed would provide military assistance for Mary’s triumphal return to Scotland’s throne.

Instead, Mary was held prisoner in England for 19 years, in part because Cecil remained convinced that Mary would try to seize the English crown. Mary was eventually convicted of conspiring against Elizabeth and executed for treason. While the two queens were relatives who corresponded frequently and shared the rare experience of being women in power, they never actually met face to face (a fact so startling that an upcoming film about Mary, to be released next month, invents a dramatic confrontation between the two monarchs).

Mary’s story has been often told, but it has been interpreted differently through the generations. While some earlier historians viewed the queen as complicit in her rape and subsequent marriage, Williams analyzes events with a modern perspective, incorporating what we now know about the trauma of sexual assault. The author also stresses how the two queens, unlike kings who governed autocratically, were consistently forced to relinquish some of their power. In framing Mary’s story as being one about “how we really think of women and their right to rule,” Williams hints at its ongoing resonance.