Bella Abzug: Liberal trailblazer in a broad-brimmed hat

Leandra Ruth Zarnow’s “Battling Bella” traces Abzug’s activism in the 1970s and forecasts the arrival of greater numbers of women in politics.

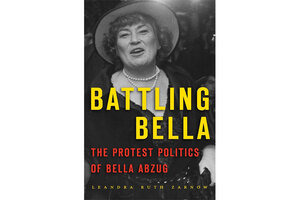

“Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug” by Leandra Ruth Zarnow, Harvard University Press, 464 pp.

Courtesy of Harvard University Press

“There are those who say I’m impatient, impetuous, uppity, rude, profane, brash, and overbearing,” one-of-a-kind U.S. Rep. Bella Abzug once characterized herself. “But whatever I am – and this ought to be made very clear – I am a very serious woman.”

In “Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug” by Leandra Ruth Zarnow, this serious woman is the subject of a serious political biography, one that’s more narrative than the excellent 2007 volume from Suzanne Braun Levine and Mary Thom and likely appealing to a broader audience than Alan H. Levy’s groundbreaking 2013 book. Extensively researched (the end notes run almost 100 pages) and engagingly written, “Battling Bella” places Abzug firmly in the context of her time – the contentious politics of the 1970s – as well as positions her as a trailblazer whose brash style anticipated the personality-driven culture of the 21st century.

Born in 1920 in New York City, Abzug received her law degree from Columbia in 1944. Her political career began in 1970 when she won a seat in the House of Representatives and earned the nickname “Battling Bella.” In 1972 she lost a Democratic primary race against William Fitts Ryan, who died before the general election (Abzug won in the general election against Ryan’s widow). Zarnow, assistant professor of history at the University of Houston, relates that Abzug was a natural at street-level campaigning. “Her strategy was not to play up to femininity but to deconstruct it by presenting herself as sincere, confident, and forward,” she writes. “Her magnetic charisma won over many, who often called out, ‘Hey, Bella’ as she made her rounds.”

Her reception wasn’t always so gratifying. In the mountains of hate mail she received, one Democrat wrote scathingly, “You have made a Republican out of me,” and even the progressives whose ideology she so often reflected could find fault. “I don’t believe women are going to get liberated by attacking the male,” she said at one point, for instance. “Women must fight for and win a political structure that mirrors reality, not defies it.” As Zarnow points out, “to younger feminists receiving this criticism from a fifty-year-old woman, the dismissal felt parental.”

Abzug stayed in Congress until 1977. In that time, she led the Women’s Movement, championed important legislation in defense of minority and gay rights, and helped to found the National Women’s Political Caucus. Zarnow refers to 1972 as “a breakthrough year for women in politics” – 75 women ran for Congress and three ran for president. In deciding whom to support, Abzug relied on her no-nonsense political instincts and backed candidates according to “her ideological leanings and pragmatic assessment of their viability.”

Abzug, Zarnow writes, “saw the disruption of male elites in power as a necessary measure to upend the grip of patriarchy, a system embedded in US law and government.”

The sometimes seedy bare-knuckled politics of the time permeate the book, and much to her credit, Zarnow seldom pulls punches; Abzug is presented here with her failings as well as her triumphs. Readers are told, for instance, what a terror Abzug could be toward staff members, and the scurrilous behavior of her 1972 campaign against the sick and dying Ryan isn’t skirted.

Ultimately, this approach serves to elevate Abzug; with her big hats and her beaming smile and her short temper and her blunt honesty, she becomes in Zarnow’s handling an intensely admirable flesh-and-blood character. Her personal life is treated in less detail than her political struggles, but this is almost certainly what she herself would have wanted. And Zarnow’s focus on her subject’s central importance never wavers. “For much of her life,” she writes, “Abzug gained strength by working at the periphery as a defender of the defenseless – workers, racial and sexual minorities, political radicals, new immigrants, and women – in challenge of the status quo.”