Ida Tarbell and the magazine that helped break up Standard Oil

“Citizen Reporters” tells of tenacious journalist Tarbell, and the eccentric editor S.S. McClure, who gave McClure’s magazine its clout.

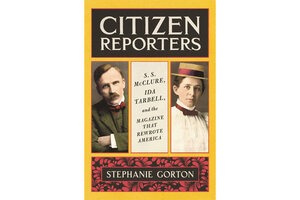

“Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine That Rewrote America” by Stephanie Gorton, Ecco, 368 pp.

Courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers

Income disparities, technology-induced displacement of workers, and political corruption were at the heart of America’s Gilded Age in the late 19th century. While “yellow journalism” exploited scandals and spread falsehoods, some reform-minded journals set out to expose society’s ills through investigative reporting.

While little remembered today, McClure’s was a landmark magazine and a vivid reminder of the power of journalists to expose wrongdoing and compel change. In “Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine That Rewrote America,” Stephanie Gorton weaves an entertaining history of this important journal and the people responsible for its success. While centered on events that occurred between 1890 and 1910, the tale she tells feels relevant today.

Sam McClure and his family emigrated from Ireland to America in 1866, after his father died. The family were subsistence farmers. McClure worked his way through Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, where he founded the student newspaper and was well known on campus for his tenacity and energy.

In the early 1890s he established his eponymous magazine in New York City and built it around a stable of writers that included Jack London, Ray Stannard Baker, Upton Sinclair, Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson, Willa Cather, and Mark Twain.

Despite this all-star roster, nobody was more important to his magazine’s success than Ida Tarbell. Her father was part of the mid-19th century oil boom in Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, John D. Rockefeller and Henry Flagler’s Standard Oil Co. would eventually put Franklin Tarbell and many of his neighbors out of business.

McClure’s major innovation was turning his journalists loose to examine a massive subject without regard to deadlines or cost. Lincoln Steffens, as Gorton details in her book, investigated municipal corruption in St. Louis, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia in a series known as the “Shame of the Cities.” Baker wrote “The Right to Work” in 1903 about a strike and the terrifying working conditions facing coal miners in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

More than anyone else, Ida Tarbell demonstrated what such journalism could really accomplish. In a 19-part series published between November 1902 and October 1904 she produced a devastating portrait of Standard Oil and its pervasive, corrupt business practices.

She spent four years researching the story and relied on extensive interviews, public records, and private documents. Later published as a two-volume book, her work is widely credited with pressuring the federal government to break up the company.

Yet even as the magazine brought attention to serious issues, there were problems in the office. Largely they were caused by McClure himself. A brilliant man, he was, in Kipling’s words, “a cyclone in a frock-coat ... he’d kill me in a week with mere surplus of energy.” He was given to taking long trips to Europe to identify new topics for his writers. He would then return to the office overflowing with ideas and totally upend the business of publishing.

Tarbell was caught in the middle. “Miss Tarbell could not escape the fact,” writes Gorton, “that she had become both the Chief’s conscience and the staff’s best hope to right the ship.” Personally, she wanted “nothing more than to be left alone.” No such luck.

There are plenty of books about McClure, Tarbell, and McClure’s magazine. What Gorton does is provide a lively narrative that brings the three together in a strong, well-written, and compelling volume. Extensively researched, the book is written with flair. Readers will find themselves caught up in the story and rooting for the protagonists.

It’s easy to note parallels between the events that Gorton so effectively recounts and our own time. To wit: bitter debates about America’s place in the world, widespread and increasing income inequality, fears that large corporations have too much power, and a president who condemns the media as “corrupt” and “an evil propaganda machine for the Democratic Party.”

Gorton is too careful a writer to overstate the connections and notes: “The parallels between the Gilded Age and today are not neat enough to draw easy lessons from the rise and fall of McClure’s.” Agreed. But readers are likely to come away with the impression that, as the saying goes, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”