Artificial Intelligence still has a long way to go

In "You Look Like a Thing and I Love You," researcher Janelle Shane gives a down-to-earth explanation of the state of AI research.

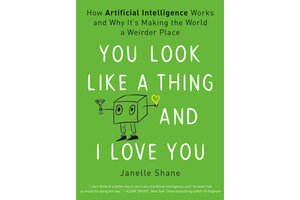

“You Look Like a Thing and I Love You: How Artificial Intelligence Works and Why It’s Making the World a Weirder Place” by Janelle Shane, Voracious, 252 pp.

Courtesy of Hachette Book Group

When most of us think “artificial intelligence” our minds may turn to science fiction: the endearing android Lieutenant Commander Data from “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” or the murderous Cylons – the robots who turned on their human creators in “Battlestar Galactica.”

On a more mundane and – to some – more realistic level, many fear that AI will eliminate jobs currently occupied by humans. (Think driverless vehicles making human truck drivers obsolete.)

But scientists working on artificial intelligence spend more time struggling with the field’s limitations than they do exploring its possibilities, dystopian or otherwise. At least that’s the premise of Janelle Shane’s “You Look Like a Thing and I Love You: How Artificial Intelligence Works and Why It’s Making the World a Weirder Place.” Shane, an optics research scientist and the author of the blog AI Weirdness, is thoroughly familiar with AI’s shortcomings: her book’s title was produced by an algorithm she wrote to compose pickup lines. Drawing on her own and other researchers’ experiences with machine learning programs, she’s written a funny and fascinating introduction to what exactly scientists mean when they say “artificial intelligence” – and how it is and isn’t intelligent.

“Artificial intelligence” is a catch-all phrase for the field of research that seeks to create smart computers. Modicums of computer intelligence manifest most easily in well-delineated tasks – the more focused the task, the better the computer’s performance. But trouble starts when a scientist programs an algorithm to do tasks that require a wealth of knowledge humans take for granted.

In 2016, for example, a human driver decided to use a Tesla car’s autopilot function – which is designed for highway use – on a city street. The vehicle ran into a flatbed truck while it was crossing an intersection because the autopilot could only recognize trucks coming from behind the car. Instead, the AI identified the truck as an overhead sign.

But while Shane acknowledges the very real dangers posed by the limits of AI, she focuses on the lighter side of the subject. In lively, conversational prose, she provides accessible illustrations of basic AI concepts. For example, take two of Shane’s “Five Principles of AI Weirdness”: AIs don’t understand the problems you want them to solve, and AIs take the path of least resistance to their programmed goal. Case in point: Shane later discusses an algorithm that was supposed to write programs that would perform basic computing tasks using minimal power. The algorithm’s solution? It created programs that were permanently asleep so they wouldn’t use any resources.

Shane occasionally returns to the darker side of AI. A commercial algorithm used by many states to recommend prisoners for parole was found to be much less likely to recommend African-American prisoners for early release, regardless of their conduct or age. That’s because the algorithm was trained using datasets compiled from the historical records of this country’s justice system, whose judges disproportionately condemned African American offenders to harsher sentences than white offenders. In other words, the algorithm recorded and repeated human bias. When AIs don’t work, sometimes the problem isn’t AI – it’s humans, Shane notes.

AI’s myriad failings stand in stark contrast to its cutting-edge cachet. Despite the technology’s vaunted promises, there are still many tasks – even technical ones – that humans do better. But because of the fanfare that surrounds AI (and the field’s ability to attract investors), companies sometimes misrepresent work done by humans as the fruits of AI. Shane points out that in 2019, an estimated 40 percent of European startups claiming to develop AI didn’t use any at all.

“You Look Like A Thing” provides an eye-opening look at a serious but sometimes oddly funny subject. And I don’t know that I could have wished for a better guide than Shane; I never expected reading about computer science to be so much fun. Ultimately, I found this book comforting: Shane makes a convincing case that AI isn’t going to be stealing jobs in the near future.