Lively memoir ‘The Watergate Girl’ tells a prosecutor’s story

Jill Wine-Banks tells of her role as a young lawyer working with Archibald Cox during the trials of those involved in the Watergate cover-up.

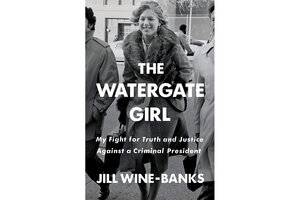

“The Watergate Girl: My Fight for Truth and Justice Against a Criminal President” by Jill Wine-Banks, Henry Holt, 258 pp.

Courtesy of Holtzbrinck Publishing Group

It’s not hard to guess why Jill Wine-Banks chose this year to bring out her memoir, “The Watergate Girl: My Fight for Truth and Justice Against a Criminal President.” The former Watergate prosecutor and ubiquitous MSNBC pundit says she used to think that Watergate was a perfect storm, a never-to-be repeated catastrophe, but she writes, “I know better now.”

While Wine-Banks holds forth on her opinion of President Donald Trump’s conduct every time she appears on-camera, she does less of it in these pages. Instead, she recollects her days as one of three assistant special prosecutors in the trial of Richard Nixon’s associates half a century ago.

The centerpiece of these memories is her cross examination of Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, on the stand. Woods testified that she was the one responsible for accidentally erasing part of the White House tape recordings, the infamous 18-and-a-half minutes missing from the tapes. The secretary demonstrated the maneuver in court, a contortion so impossible that it seemed clear she was lying to protect her boss. Yet even in the heat of the moment, Wine-Banks could not help but feel some sympathy. “I saw something of myself in the president’s trim, copper-haired secretary,” she writes, “in the way we’d both had to survive in a world of men who’d often bullied and belittled us.”

The bulk of “The Watergate Girl” is given over to describing that world, and Wine-Banks has chosen to employ a highly passionate and personal voice in crafting the narrative. The more you read, the more uncannily effective this choice becomes. She has been a trailblazer in many legal skirmishes since Watergate, but her decision to write this book in the excited, impressionistic tones of her 1971 self serves to make the book very immediate reading.

When she’s watching former Nixon White House aide Jeb Stuart Magruder plead guilty, for example, she’s nervous that the deal will fall apart at the last minute: “I saw our case against ... the rest of Nixon’s men crumbling, along with my future,” she writes. “I saw the press blaming me – a woman! – for not being tough enough to bring Magruder to heel.”

Throughout the course of “The Watergate Girl,” she proves she is tough enough. Her portraits of her colleagues, especially of special prosecutor Archibald Cox, are warmly affectionate, but it’s her cumulative portrait of herself as a smart, courageous true believer during one of the country’s darkest moments that becomes the book’s most memorable feat of dramatic reconstruction.