‘Red Comet’ is the biography Sylvia Plath has always deserved

Plath is often reduced to a punchline or mythologized as a “high priestess of poetry.” A new biography paints a more generous – and human – portrait.

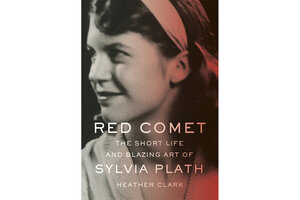

“Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath” by Heather Clark, Knopf, 1152 pp.

Penguin Random House

“Since her suicide in 1963, Sylvia Plath has become a paradoxical symbol of female power and helplessness whose life has been subsumed by her afterlife,” writes Heather Clark in her magnificent new book “Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath.” “Caught in the limbo between icon and cliché, she has been mythologized and pathologized in movies, television, and biographies as a high priestess of poetry, obsessed with death.” If Clark’s goal in writing this big book, nearly a decade in the making, was to swap out that tired, overworked symbol for a three-dimensional human, in “Red Comet” she has succeeded far beyond the extent of all previous Plath biographies.

Despite the fact that she died by her own hand at the young age of 30 – or maybe because of that fact – Plath has never lacked for those biographies, and the short story they all tell is roughly the same in outline: Plath was born in Boston in 1932, and she very early set herself on the course of a professional writer, firing off poems and articles even while still a young girl (her first national publication came just after high school, in the pages of the Christian Science Monitor). She attended Smith College, won a guest editorship position at Mademoiselle magazine, but also began to be stalked by depression, for which she underwent electroshock therapy in the early 1950s and which drove her to her first suicide attempt in 1953.

As Clark points out, Plath read the writings of British poet Ted Hughes before she met the man himself. Only months after that first meeting they married, in 1956, and the late 1950s found the couple living in Boston, with Plath working as a receptionist in the psychiatric wing of Massachusetts General Hospital and, it often seems, feeling estranged from the artistic inspirations steadily growing and complicating inside her. “Plath’s desire for reinvention was American, but her transformation could not occur in the United States,” Clark writes. “In late 1959, she left America for England with Hughes, never to return.” There followed in 1960 the publication of Plath’s first poetry collection, “The Colossus,” and her novel, “The Bell Jar,” in January of 1963.

But the depression and suicide attempts continued as well, and Plath took her own life on February 11, 1963 (“The woman is perfected. / Her dead / Body wears the smile of accomplishment,” she wrote in “Edge,” a poem finished just a week before her suicide.) Clark is as perceptive about the work of this final year as she is about the rest of Plath’s writings: The “surreal grandeur of ‘Edge’ – and indeed all of Ariel and the 1963 poems – opened up new aesthetic possibilities that would change the direction of modern poetry,” she writes.

Clark has consulted an enormous array of primary sources in order to assemble this life, ranging from unpublished letters and psychiatric records to interviews with virtually everybody who knew Plath or worked with her. The result is a clearer and more comprehensive account of Plath’s life than any that have appeared before, particularly strong in analyzing the complexities of her evolving relationship with Hughes (who is here given credit as a “steward” of her work after her death) but also wonderfully detailed in giving readers a look at the life of a working author.

We follow Plath through every submission to places like the Springfield Daily News, The Springfield Union, the Daily Hampshire Gazette, The Nation, The Atlantic, Ladies’ Home Journal, Harper’s, and although Clark sometimes succumbs to the biographer’s curse of over-documentation (we get the point long, long before every single rejection slip is accounted for), this granular picture of Plath the writer is invaluable in dispelling that image of a death-obsessed high priestess. This is a Sylvia Plath who jokes and loves and encourages and horses around. It’s an intensely human portrait.

There’s an undercurrent of anger to much of this, an undercurrent Plath herself would have appreciated. This poet has become a “cultural shorthand for female hysteria,” but as Clark notes with some asperity, “Male writers who kill themselves are rarely subject to such black humor.” As Clark puts it, “Sylvia Plath took herself and her desires seriously in a world that often refused to do so.”

“Red Comet” takes Plath and her work very seriously, and with a refreshing degree of reserved historical distance. Despite being grounded in all those primary sources from Plath’s lifetime, “Red Comet” feels bracingly free of old grievances and shopworn vindications. It’s the big, generous biography Plath has always deserved.