‘A migrant in my own life’: A playwright looks deep within.

In “My Broken Language,” Tony award-winning playwright Quiara Alegría Hudes explores Latino identity in a raw, honest, and loving memoir.

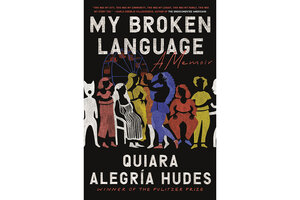

"My Broken Language" by Quiara Alegría Hudes, One World, 336 pp.

Penguin Random House

Far too often, there’s a stopping point for Latinos attempting to uncover family history. There are blank spots and questions not easily answered, spaces filled with wounds and lost stories. Quiara Alegría Hudes embarks on a pilgrimage to discover more about her family’s roots in her memoir, “My Broken Language.”

Hudes rose to prominence as the book writer for the Tony-winning musical “In the Heights” and won a Pulitzer Prize for her play “Water by the Spoonful.” Her writing in these two shows highlights her precision, clarity, and candor. That same energy is found in “My Broken Language,” a raw and eloquent memoir that follows Hudes’ childhood in Philadelphia to her adulthood as an undergraduate at Yale and later to Brown University where she took playwriting workshops under the guidance of award-winning playwright Paula Vogel. Throughout, she describes making her way through life lessons communicated in English, Spanish, and Spanglish. “My Broken Language” is at once nuanced, loving, empowering, and melancholic.

The memoir opens with Hudes’ family – her mother is from Puerto Rico and her father’s background is Jewish – moving out of their multilingual West Philadelphia neighborhood to largely white, suburban Malvern, Pennsylvania. It was Hudes’ first realization that not all neighborhoods had residents who spoke multiple languages.

Once she arrives in Malvern, the children in school taunt her. “What are you?” they want to know. “‘I’m half English, half Spanish,’ I ventured, as if made not of flesh and blood but language,” Hudes writes. From an early age, Hudes grasps the ways that language reflects, distorts, and makes demands. The only Spanish she hears is spoken by her mother, never in her father’s presence, during forays to the hilltop near their home where her mother tells her about the spirit world. Despite the dislocation Hudes feels from being separated from Philly friends and her extended family, she is exhilarated by the chance to bond with her mother.

Readers feel the tension of Hudes’ adolescent and college years as she’s trying to figure out how to be; she doesn’t allow for easy binaries, nor does she attack who or what makes her question herself as she explores what it’s like to be a Latina girl, and later a Latina woman, in contemporary U.S. society.

For Hudes, language remains the main point of tension: “I was a migrant in my own life,” she writes. She feels inadequate on several fronts: She is neither Puerto Rican enough nor white enough and she doesn’t know enough about composer Stephen Sondheim.

She also inherits the matrilineal teachings of Santería and the language attached to it, along with knotty, unresolved situations. At one point, she questions if her Spanish is strong enough to continue studying Santería. The ceremonies call out to the spiritual world and are seen as a decolonization effort by many people in the diaspora, Puerto Rican and otherwise. Hudes supplements the information she acquired at home by reading books like “Four New World Yoruba Rituals.”

Hudes intentionally resists tying together her experiences into neat narrative bows. “My Broken Language” prompts rethinking of the representation narrative, who it is designed for and who it liberates – if anyone – which will undoubtedly create roadblocks for some readers. Even though we exist in an increasingly globalized landscape, we’re still consumed by feel-good narratives of cross-cultural exchange. The success of Latino artists like Hudes can be considered an antidote to political and social oppression, but it doesn’t mean the trauma is gone or that she has found all the answers.

But there’s an undeniable catharsis in seeing such an excellent writer communicate what many Latinos struggle to express about language. It encourages a reevaluation of the relationship with language – no matter how fraught the inheritance. There is a brutal honesty that Hudes brings to Latina girls and women’s experiences, which is vital to understand as women strive to have their voices heard and believed. It’s the key to repairing the broken systems that have long defined the United States.