Afghanistan’s first female pilot paid a steep price for the freedom to fly

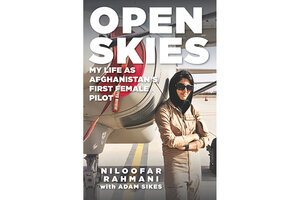

Now in exile, Niloofar Rahmani writes of her journey to become the Afghanistan’s first female pilot in the memoir, “Open Skies.”

Chicago Review Press

When Niloofar Rahmani was a teenager in Afghanistan, she confided in her best friend that she wanted to be a pilot someday. Her friend laughed, replying that “In Kabul, the only things that fly are pigeons and the Americans.” The response was understandable: It was only a few years after 9/11, and while the Taliban were no longer in power and Rahmani was finally attending school along with other neighborhood girls, women were still treated like second-class citizens. Her ambition seemed almost delusional.

“Open Skies: My Life as Afghanistan's First Female Pilot” is Rahmani’s compelling account of how she achieved her unlikely dream. The author was born in Afghanistan in late 1991, but within months her family had fled to a refugee camp in Pakistan to escape the civil war that brought intense fighting to Kabul. After three years in the camp, they settled into an apartment in Karachi, but several years later, homesick and weary of living as refugees, her parents moved the family back to Afghanistan, which was by then under Taliban control.

Kabul had once been known as the “Paris of Central Asia.” But upon her family’s return in 1999, Rahmani writes, “there was no music, there were no colorful kites in the air, there were no bustling bazaars, and there were no travelers who’d come from faraway places.” Worse, there was “no place for women ... except as modern-day slaves who were treated worse than animals.”

Rahmani describes the brutal years that followed. Shortly after their return to Afghanistan, the Taliban kidnapped her 18-year-old neighbor, killing the teenager’s father when he tried to intervene. Later, Rahmani’s mother, rushing out of the house in flip-flops to take Rahmani’s ill sister to a doctor, was publicly whipped for exposing her feet.

After 9/11, which led to the American invasion and the toppling of the Taliban regime, Afghan women regained many rights. Rahmani enrolled at a new girls school, where she thrived. In 2009, with the U.S.-led coalition helping to develop Afghanistan’s armed forces, the Afghan air force began recruiting women to be pilots. With the blessing of her remarkably supportive father – she is gratified when he proudly tells her “You are like a son to me” – Rahmani immediately enlisted.

The author recalls challenges she faced, ranging from a lack of women’s bathroom facilities to the extreme hostility she faced from Afghan men in the military. Like the other female recruits she met, Rahmani kept her training a secret, lest she shame her family. Even her younger siblings were unaware of what she was doing.

Despite the extremely challenging conditions, Rahmani made it through basic officer training, air force orientation, and English language instruction. Then, finally, she was allowed to learn to fly combat missions. Even though she had never been in an airplane before pilot training, she immediately took to flying. Being in the air also offered her a new perspective on life. “Up here in the sky, where the birds flew, I felt incredible freedom and unbridled euphoria,” she writes.

In 2013, Rahmani became the Afghan air force’s first female fixed-wing pilot. Unfortunately, however, word got out, and the consequences were devastating. Her father lost his job, her sister’s husband kicked her out of the house, and her brother was the target of two assassination attempts.

In addition to feeling responsible for her family’s distressing circumstances, Rahmani struggled to reconcile the extremes of her life. “I was a captain in the air force commanding an aircraft and responsible for the lives of everyone on board, flying missions throughout the country,” she writes. But to get to and from the base, she had to disguise herself in the burka she had shed years ago, “doing my best to remain invisible” to those who would kill her.

These extraordinary events make for gripping reading, but the book is often hampered by repetition and cliché. But the story comes alive when Rahmani includes specific details, whether describing a treasured childhood treat – shir yakh, an ice cream flavored with saffron and cardamom – or revealing that “Top Gun” is her favorite movie of all time.

Still, it’s impossible not to admire Rahmani and marvel at her courage. Now, as the Taliban regains control of Afghanistan, it’s also impossible not to worry about what awaits the women of Afghanistan. Rahmani is no longer living there: In 2019, she was granted asylum in the United States (her family was also forced to leave the country, although Rahmani declines to reveal where they settled). She has applied for American citizenship and plans to join the U.S. Air Force in the hopes of flying again someday.