From the particular to the universal: Cross-cultural stories

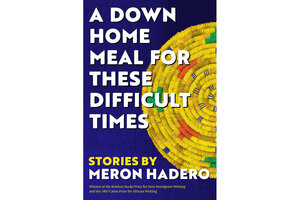

“A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times” by Ethiopian American writer Meron Hadero highlights immigrant stories of dislocation and identity.

"A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times," by Meron Hadero, Restless Books, 224 pp.

Displacement – often by outside force, rarely by personal choice – haunts Meron Hadero’s superb debut short story collection, “A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times,” which won the 2020 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing and hits bookstores this week. Like many of her characters, Hadero is all too familiar with dislocation. Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, she arrived in the United States as a child via Germany, and later earned degrees at Princeton (BA), Yale (JD), and the University of Michigan (MFA).

Her 14 stories are set between her two homes – her native Ethiopia and her adopted America. Although she's concerned with specific geographies, Hadero creates a remarkable universal resonance, exquisitely illuminating quotidian moments that could, and do, happen anywhere in the world where people long to belong, find community, and be welcomed (even when they’re not).

In 2021, Hadero made international literary history as the first Ethiopian to win the coveted AKO Caine Prize for African Writing for “The Street Sweep,” a story that's included here. Eighteen-year-old Getu prepares to attend a farewell party at the posh Addis Ababa Sheraton for a nongovernmental organization staffer whom Getu believes is his friend. As Getu gets ready, his mother is a dark voice of reason, stifling his hopes with reminders about race, class, colonial entitlement, and looming land loss. Yet Getu is convinced that this man could be his path off the streets.

In another eloquent story, “The Wall,” a 10-year-old Ethiopian refugee lands in the Midwest after living in Berlin. His first American friend is, ironically, another Berlin transplant with whom he shares so much – language (German, and the English lessons the older provides the younger), favorite season (fall), and favorite film ("Casablanca" because it’s about refugees and true friendship). For a while, their commonalities, most especially as survivors of brutal regimes, seem timeless despite a half-century difference in age.

In numerous stories, Hadero deftly examines what it means to be Black in America, especially as a transplant from another country. In “Mekonnen aka Mack aka Huey Freakin’ Newton,” a young Ethiopian boy living in Brooklyn must quickly acclimatize to the definition and divides of race – and racism. In “Sinkholes,” the only Black child in a Florida classroom refuses to write that racial slur on the board despite the teacher’s insistence that “You can’t let a word have this much power.” In “Medallion,” an Ethiopian college student in southern California learns the most difficult life lessons “as a Black man in this country” from a former bank executive-turned-cabdriver.

In other stories, Hadero empathically and expertly explores living between cultures and countries. In the opening story, “The Suitcase,” a 20-year-old American woman visits Addis Ababa for the “first ever trip to this city of her birth,” but leaving with overpacked luggage becomes a highly-charged emotional negotiation among her relatives. Each of them has reasons for asking her to carry goods to their loved ones in America.

In the titular “A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times” – the unequivocal standout among an already stupendous collection – two women meet in 1980s New York in the back of a church classroom while their children learn Amharic. One was a scientist, the other a very wealthy woman back in Ethiopia; both are admittedly hopeless in their American kitchens. As they fret over what to contribute to a PTA bake sale, they become friends. Neither can cook initially, but the decades of their overlapping lives become trackable through their joint mastery of quintessential dishes found in the pages of “The Good Housekeeping Illustrated Cookbook.”

From narrative to narrative, Hadero is a wondrously agile writer, whether describing moments of triumphant anticipation (“that January afternoon that was so steeped in hope that you could feel its warmth despite the numbing air”); shocking devastation ("'No, no,' she said again, using her fist to argue for her life"); rightful contentment (“as Yeshi and Jazarah stood ever more firmly on ground that had to be home”). Hadero’s prodigious storytelling is part testimony, part warning, part balm. One of her characters ponders an affecting antidote: “to create a space to let joy enter her life as well, even there in prison – they were the most fleeting moments, but they were something.” Joy – and perhaps a few tears, chuckles, gasps, sighs – awaits readers here, as well.