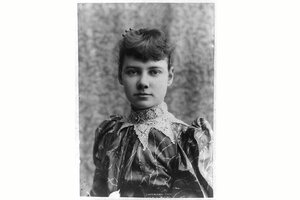

A voice that wouldn’t be ignored: Nellie Bly and the pursuit of truth

Journalist Nellie Bly was deeply concerned about social ills. Her six-part newspaper exposé “Ten Days in the Madhouse” ran in the New York World and cemented her reputation.

H.L. Meyers/Courtesy of Library of Congress

At a time when trust in the media is at an all-time low, Louisa Treger’s “Madwoman” is a thoughtful reminder of how journalism can drive positive change. A work of historical fiction, it tells the story of the real Nellie Bly (1864-1922), the first female investigative reporter who not only demanded justice from powerful institutions, but also insisted on dignity and compassion for the most vulnerable citizens.

Treger deftly weaves together Nellie’s story, taking liberties with the details but cleaving to as many of the biographical facts as possible. Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran and nicknamed “Pink,” she was a spirited girl interested in playing with her brothers, listening to the imaginative tales of her mother, and reading quietly with her father, a prominent judge. Hungry for knowledge and ambitious from a young age, Nellie seemed to have it all. But what started as a charmed life quickly took a turn, as her father died unexpectedly and her mother found herself in an abusive second marriage.

The trauma and poverty that followed nearly left Nellie destitute, unable to pursue a career in law that her father once supported.

Why We Wrote This

Persistence is needed to uncover wrongs and chart a course toward change. In the 19th century, a female reporter courageously put herself on the line to reveal the truth.

Through a series of events, rooted in her quick wit and passion, she found herself on the staff of the Pittsburgh Dispatch, writing articles that shocked the city. From there, she ventured to New York City to try her hand reporting for some of the biggest publications in the field.

Treger makes it clear that Nellie’s professional aspirations were not welcome; everyone from family members to sources to other journalists reinforced the notion that women could not be reporters. And yet she persisted. Her perseverance was driven by her conviction that this was her calling. Treger writes of Nellie’s commitment to becoming a reporter:

“It was storytelling with a difference. It involved delving into complexity, bringing gray areas of morality to light; and it was backed up by collating evidence and finding justice. Journalism reconciled the contributions of both her parents.”

The novel really takes off when Nellie must prove herself to the editors of the New York World. In a bid to get their attention, she pitched an impossible story, offering to go undercover as a patient to Blackwell’s Island, home to an infamous asylum for people with mental illnesses. The editors decided to give her a shot.

In real life, Nellie did get herself committed, endured imprisonment, and successfully reported the events she witnessed once released. It is a harrowing tale – not just that Nellie’s experience was horrific, but that she voluntarily experienced these conditions to reveal them so others might be spared. Still, it’s hard to know which events in “Madwoman” are factual and which are embellishments, as Treger warns the reader ahead of time that “where gaps exist in the records, [she] felt free to invent.” A note at the end of the novel provides Treger’s source material.

Through Nellie’s descriptions of the women with whom she was incarcerated, it becomes easy to see that “insanity” and “madness” were essentially catchall diagnoses for anyone who didn’t fit society’s expectations. Women who were unfaithful to their husbands, or who didn’t speak English, or who grieved the loss of a child were thrown into the facility with little hope of care or recovery. What’s more, the treatment was so brutal that Nellie reflects, “Here was where the madness lay – in being imprisoned in this space, trapped and caged like an animal.”

Her reports spoke of the rapid physical and mental deterioration of women in such conditions. As she says of one patient, “It was painful to watch her folding herself up and packing herself away, retreating to some place deep inside.” The novel portrays the reality that people’s mental health falls on a spectrum, and how they are treated can mean the difference between a life of agency or one of despair.

Some portions of the book are graphic; Nellie herself suffers abuse at the hands of the nurses on multiple occasions. One particular scene goes beyond physical violence into deep humiliation and dehumanization. Given these powerful portrayals, the reader comes to the same conclusion as Nellie: Something had to be done.

Her compassionate inquiry into the lives of women who were institutionalized served as a catalyst for her own efforts and agency. Her story is the perfect example of the power of an individual to question, and change, the status quo.