The path to Hiroshima and Nagasaki began with the firebombing of Tokyo

'Black Snow' examines the U.S. firebombing of Tokyo in 1945, and public attitudes toward targeting civilians, which set the stage for use of the atomic bomb.

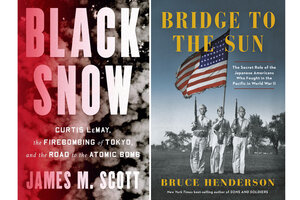

"Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb," by James M. Scott, W. W. Norton and Company, 432 pp. "Bridge to the Sun: The Secret Role of the Japanese Americans Who Fought in the Pacific in World War II," by Bruce Henderson, Knopf, 480 pp.

In early 1945, as World War II in Europe staggered toward a conclusion, U.S. military leaders looked uneasily toward the Pacific. Japan showed no willingness to lay down its arms, but after 3 1/2 years of war, the American public was tired of conflict, and the casualty projections for an anticipated invasion of Japan were very high.

To Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, head of the Army Air Force, this was an opportunity. If he could use his brand-new massive B-29 Superfortress bomber to bring the war to a swift conclusion, he would strengthen the case to establish the Air Force as a separate branch of the U.S. military. In “Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb,” historian James M. Scott recounts what happened next.

From the beginning of the war, the United States practiced high-level “precision bombing,” which targeted military objectives and sought to minimize civilian casualties. The British, having been subjected to the Blitz, were in favor of “area bombing,” which, while prioritizing military installations, acknowledged that civilians in the target area were at risk.

But the Air Force had a dismal record of putting bombs near the target in Japan, mostly because of the winds at high altitude over the island kingdom.

After months of futility, Arnold replaced the head of the 21st Bomber Command with a highly respected and aggressive young commander named Curtis LeMay. His solution was to abandon high-level, daylight precision bombing in favor of low-level, night area bombing. Rather than high explosives, LeMay would use only incendiary bombs, which were simply designed to start fires.

Most Japanese buildings were made of wood, and population density was sometimes as high as 100,000 people per square mile. On March 9, 1945, LeMay launched 300 bombers for a night attack on a part of Tokyo packed with small manufacturing firms and tens of thousands of people.

The raid lasted just 142 minutes, but results were devastating. Some 16 square miles of Tokyo were incinerated – more than 10,000 acres. An estimated 267,171 homes, stores, and businesses were destroyed. “The magnitude of the destruction and loss was almost impossible to comprehend,” Scott writes. “Residents had gone to bed the night before ... only to awaken to a world on fire.” Only 14 bombers were lost.

Historians now estimate that 105,000 people died that night. Scott makes brilliant use of firsthand accounts to describe the experience of those on the ground.

Air Force officials believed that LeMay had found the key to ending the war. Over the next five months, U.S. bombers “burned more than 178 square miles of sixty-six cities, which were home to more than 20 million men, women, and children.” Later estimates concluded that these raids killed 330,000 people and injured another 473,000.

At home, the results of the big raid were cheered – it was payback for the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. LeMay was aware that he was targeting civilians. “If we lose,” he confided to an aide, “we’ll be tried as war criminals.” But neither then nor later did he seem troubled: “I was not happy, but neither was I particularly concerned, about civilian casualties on incendiary raids,” he later recalled.

But Scott notes that later, dispassionate observers took a far dimmer view. The 1947 official U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey simply said, “The raid of 10 March was clearly one of the greatest catastrophes in all history.” Another bombing report noted, “Probably more persons ... lost their lives by fire at Tokyo in a six-hour period than at any time in the history of man.”

It was, of course, the atomic bombs that ultimately ended the war. But Scott persuasively argues that the path to Hiroshima and Nagasaki began with the firebombing of Tokyo five months earlier. There was little debate about the morality of killing so many civilians with an atomic bomb, he suggests, because the U.S. had already decided that civilian casualties were just part of war.

The raids that were so welcomed at the time look horrifying nearly 80 years later. But a fair reading of American history requires that we look at all sides of the story, even if they are inconsistent with the image that we hold of ourselves. Exhaustively researched and well written, Scott’s book is a key part of understanding a fuller picture of World War II.

Bridge to the Sun

If “Black Snow” is thought-provoking and deeply troubling, Bruce Henderson’s brilliantly researched and superbly written book, “Bridge to the Sun: The Secret Role of the Japanese Americans who fought in the Pacific in World War II,” is filled with grace, courage, and patriotism.

The stories of the U.S. Army’s 442nd regiment, composed of Japanese Americans who fought in Europe with great bravery, are legendary and oft-told. Largely unknown is the story of the roughly 3,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry who acted as translators, interrogators, and interpreters in the Pacific theater.

Japan’s military believed that the complexity of the language would make it impossible for their plans to be interpreted, so they did not always communicate in code. What they did not count on were a few young Americans – many of whom had been educated in the United States and Japan – who spoke both languages fluently. When these messages were intercepted and translated, it gave the Americans a secret weapon.

Henderson follows six young men, growing up in 1930s America and, for various reasons, finding themselves in the U.S. military. In four of the cases, their parents were living in internment camps during World War II. The stories are heartrending. One tearful mother in a guarded compound sent her departing son off to war with one plea: “Make us proud.”

As Henderson writes, these men “fought two wars simultaneously: one, against their ancestral homeland; the other against racial prejudice at home.”

The inspirational story of these men at a crucial juncture in American history makes for gripping reading. More importantly, as Henderson notes, “In an America that too often prejudices people based on race and ethnicity, their timeless message of courage and patriotism should not be forgotten.”