Where morality and politics collide: How Abraham Lincoln held his ground

Lincoln was by no means perfect, but his convictions took the country forward, writes historian Jon Meacham in “And There Was Light.”

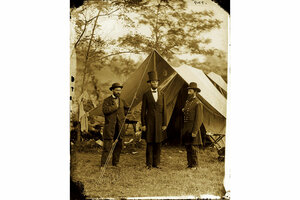

President Abraham Lincoln, flanked by his bodyguard Maj. Allan Pinkerton (left) and Maj. Gen. John McClernand (right), visited Union troops in 1862, a few weeks after the battle of Antietam.

Library of Congress

Not long after Abraham Lincoln was elected 16th president of the United States, South Carolina seceded from the Union. In the months leading up to his March 1861 inauguration, various politicians and business leaders appealed to the president-elect to compromise with the South in order to avert a civil war. The most developed plan, the Crittenden Compromise, proposed constitutional amendments protecting slavery where it existed and allowing its spread to southern territories, but prohibiting its expansion in the northern territories.

Lincoln would not entertain it. As Jon Meacham observes in “And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle,” “In these cold and complex months, Abraham Lincoln was both statesman and moral being, choosing the difficult over the easy, the catastrophic over the convenient, the right over the wrong.”

Meacham’s sweeping, elegantly written biography, a welcome addition to the vast library of work on the 16th president, is largely focused on what made Lincoln stand his ground, then and in 1864. By that time, the Civil War was raging, his reelection was in doubt, and he was again urged to negotiate with the South on the issue of slavery. The Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer concentrates on the president’s complicated balancing act between moral principle and political calculation, demonstrating Lincoln’s evolution toward a more expansive view of liberty. Meacham’s Lincoln is willing to change and grow as he struggles to lead the country through calamitous times; in doing so, he has much wisdom to offer our age.

The book begins with Lincoln’s early years, showing that his anti-slavery feelings dated back to his impoverished childhood in Kentucky and Indiana, where his family belonged to anti-slavery churches. Lincoln always held the conviction that slavery was wrong. Self-educated as a lawyer, he also believed, as many then did, that the federal government did not possess the authority to abolish slavery where it already existed. While he saw slavery as protected by the Constitution, Lincoln looked back to an earlier document, the Declaration of Independence, regarding its assertion that “all men are created equal” as, in Meacham’s words, “a goal to seek, an ideal to realize, a promise to fulfill.”

“And There Was Light” is not a hagiography; Meacham is clear-eyed on Lincoln’s shortcomings, even as he notes that they were often consistent with the dominant climate of the times. During the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates held over the course of his failed 1858 Senate race against Stephen Douglas, Lincoln said, “I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races.” Until late in the war he supported the voluntary removal of Black people from the country. As Meacham notes, Lincoln was “a white man in a white-dominated nation shaped by anti-Black prejudice that he to some extent shared.”

The author also points out that the opponents of emancipation weren’t confined to the secessionist states, reminding us that while the Civil War is remembered as a battle between North and South, that framing is an oversimplification. “He was a minority president,” Meacham writes. “He faced opposition not only in the Confederacy but in the tenuously loyal border states; and the Union itself was far from monolithic.”

Despite the political risks, however, Lincoln eventually determined that the war must end slavery, and he committed to emancipation. (He issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.) “Lincoln believed he was acting according to motives higher than the merely political,” Meacham explains. The author considers, as many others have before him, the role of religion in the president’s decision-making. While it’s impossible to know his beliefs, it seems clear that the 1862 death of Lincoln’s 11-year-old son Willie led the president to think deeply about divine providence and the will of God, not only in terms of his personal life but in the context of his presidency as well.

Meacham counterpoints the president’s lifelong expansion of his understanding of liberty with a very different evolution of views in the Dixie states. He refers to the “hardening white Southern view” that slavery, once regarded as a necessary evil, was in fact, in the 1837 words of former Vice President John C. Calhoun, a “positive good.” “Such delusions about its own virtue would fuel the rise of the Lost Cause in the postwar world,” the author writes, referring to the distorted ideology that views the Confederate cause as honorable and heroic.

Meacham seems to be alluding to our own time when he speaks of the dangers of a zealous belief, divorced from reason, in the rightness of your cause. Lincoln, on the other hand, exemplifies the possibilities of humble moral leadership, rare as it is, to inch us closer to realizing our national ideals.