Brought up in one family, but belonging to another

Stolen from the hospital as a newborn, she grew up thinking the woman who raised her was her mother. Learning the truth as an adult leads to soul-searching in the novel “Mother Tongue.”

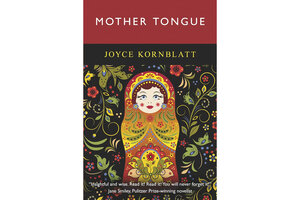

“Mother Tongue,” by Joyce Kornblatt, Publerati, 178 pp.

A story of learning to accept life’s harsh truths and not lose hope in the midst of despair, “Mother Tongue” by Joyce Kornblatt illustrates the intertwined nature of pain and personal growth. In the words of Nella Pine, the main character, it’s one of life’s mysteries: “Beauty resides in blight, and blight in beauty – each holds the other like a seed in its hand.”

The novel, first published in Australia in 2021, follows 45-year-old Nella as she discovers that Eve, the woman she knew as her mother, was not her mother at all: rather, Eve was a labor and delivery nurse named Ruth who abducted Nella from a hospital in Pittsburgh when she was just three days old. Ruth raised her in a small Australian village, and this earth-shattering truth was discovered only after Ruth’s death. As Nella reads and rereads Ruth’s confession, she is desperate to understand why someone would do such a thing. Ruth offers little clarity or explanation. “I was compelled,” she writes.

The reader follows Nella’s emotional journey as she tries to express her feelings through writing. In some ways, it’s “easier to remember the pain through the prism of craft,” she writes. Nella – who learns her real name is Naomi – explores the history of both the family who raised her and the family she never knew. A series of letters, musings, and remembrances reveal just how many lives were forever changed by this terrible act. But through the stories of other characters, the reader sees how these acts don’t happen in isolation. Generational trauma plays a role in many of the characters’ lives and choices, and perhaps is one reason that Ruth was “compelled” to do something so harmful.

The majority of the book is told from Nella’s perspective. How could she have experienced a loving childhood in such a horrible situation? How can she feel affection for a woman who stole her entire life from her and replaced it with a lie? Ruth acknowledges the vastness of this rift in her confession as she writes, “I hope you can forgive me. I doubt that you will.”

The novel moves through different points in history, both the history of Nella’s abduction as well as that of previous family members (biological and not). Multiple characters are affected by trauma experienced by their ancestors. The reader hears the perspective of Nella’s husband Alex, whose mother, like thousands of young unwed Australian mothers in the 1950s through the ‘90s, was forced to give him up for adoption. As he shares his story, he points out that exploring the past can be healing. “What you think will destroy you can give you peace,” he says.

Leah, the sister Nella never met, and Deborah, her birth mother whose own Jewish parents fled Europe ahead of World War II, provide the perspective of families who have faced genocide. Each character carries these wounds, and each character is left to learn how to trust, love, and pursue healing in the midst of pain. For some, they find a path forward. Others do not.

The book is beautifully written, poetic, and heart-wrenching. It’s a window into the fortress of the soul, giving the reader an opportunity to witness the raw, nonlinear way that someone must learn to live with a broken heart. The sharing of each other’s stories becomes the pathway to redemption and a new life, as well as the fuel that keeps each person going. Kornblatt’s book shows just how beauty and blight can be interwoven, and in accepting one, the other might be embraced.