How the women’s movement transformed society

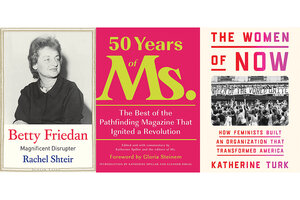

Three recent books explore the contours of the second-wave feminist movement, from titan Betty Friedan to the editors and readers of Ms. Magazine.

In 1977, former U.S. Rep. Bella Abzug, wearing a hat, and Betty Friedan, in a red coat, march to the National Women’s Conference in Houston, alongside torchbearers who had run from New York.

Greg Smith/AP/File

After Betty Friedan got her Smith College classmates to complete a questionnaire about their lives at their 15th reunion in 1957, she immediately grasped the significance of their responses. Many of the highly educated women felt trapped by midcentury America’s constrictive domestic ideals, unfulfilled by the roles of housewife and mother.

Friedan, a freelance writer and a wife and mother herself, was unable to interest any magazines in publishing her findings. She instead embarked on writing “The Feminine Mystique,” the explosive and groundbreaking book whose 1963 publication turned its author into a celebrity and, more significantly, is credited with igniting the second wave of the feminist movement.

Women’s rights as human rights

Rachel Shteir’s brisk, compelling biography, “Betty Friedan: Magnificent Disrupter,” conveys the enduring importance of her subject’s signature work, which excavated the quiet desperation of a primarily white and middle-class subset of American women. In describing what she famously called the “problem that had no name,” Friedan, according to Shteir, “laid the groundwork for women’s rights to be regarded as a civil right,” a notion that while taken for granted today was hardly obvious at the time.

Shteir’s admiring yet evenhanded book, part of Yale University Press’ “Jewish Lives” series, presents Friedan in full, capturing her restless intellect, her ferocious temper, and her maddening contradictions. “Friedan was no saint,” the author observes at the outset. “But she was an oracle and an iconoclast.” So it was from the beginning: Shteir, who conducted more than 100 interviews for the book and had access to newly opened archives, reports that as a girl, Friedan, born in 1921, organized the Baddy Baddy Club at her Peoria, Illinois, elementary school to protest a teacher she disliked.

Many of Friedan’s close relationships were difficult. She was estranged from her mother and sister for many years, and her marriage, which ended in divorce, was violent and tumultuous. Her daughter, Emily, stated as a young woman in a joint interview with her famous mother that she did not consider herself a feminist.

Friedan counted the women’s movement among her progeny. “I am here as the mother of you all,” she declared to an audience at the 25th anniversary celebration for the National Organization for Women, the advocacy group she co-founded in 1966. That relationship was also fraught. She argued frequently and sometimes viciously with other feminists, many of whom dismissed her as outdated when the movement took a more radical turn. Always concerned with “respectability,” she was excoriated for referring to lesbians in NOW as a “lavender menace,” a slur she never lived down.

Power struggles within the movement

The movement’s internecine conflicts are prominent in another recent book, Katherine Turk’s “The Women of NOW: How Feminists Built an Organization That Transformed America.” Friedan, of course, appears in this terrific history, but she’s not at its center. Instead of focusing on boldfaced names, Turk, a professor of history and gender studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, highlights the experiences of three very different women who became leaders in the group.

Patricia Hill Burnett, born in 1920, was a wealthy Republican and former beauty queen who felt unchallenged and unappreciated as a housewife. “I hated myself,” she later told an oral historian. “I hated my life.” Radicalized by reading “The Feminine Mystique,” she organized the first NOW chapter in Michigan.

Aileen Hernandez, born in 1926 to Jamaican immigrant parents in the Brooklyn borough of New York, was one of the first five commissioners (and the lone woman) appointed to the newly created Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 1965. She resigned in frustration because the panel did not take sex discrimination cases seriously, and she subsequently devoted herself to NOW, becoming its national president in 1970.

Finally, Mary Jean Collins, born to a working-class Irish Catholic family in 1939, was active in progressive politics before becoming involved with the Chicago branch of NOW. She likened joining the group in the late ’60s to “waking up from a dead sleep”; she later came out as a lesbian.

Despite their differences, the three women found common purpose – temporarily, at least – at a time when, in the author’s words, “all of the major institutions in American life treated women as subordinate and unequal.” Turk is insightful about NOW’s achievements in helping to gain equal status for women, most notably by using Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to wage legal challenges to employment discrimination.

The author is also cleareyed about NOW’s shortcomings. Amid the organization’s explosive growth – NOW had 120 members in 1966, some 20,000 in 1972, and 220,000 in 1982 – disagreements among leadership devolved into nasty, time-

consuming power struggles. (Turk describes one conference’s 20-minute debate over whether to take a 30-minute recess.) At the same time, NOW’s focus on workplace issues, and, later, on the unsuccessful fight to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, didn’t always resonate with women of color and lesbians, many of whom wanted the group’s agenda to broaden.

Radical feminists were also critical of NOW for what they considered its moderate stances and its emphasis on elite women; Gloria Steinem, the most famous feminist of the period other than Friedan, never joined, preferring the more radical group Redstockings. Neither did she invite Friedan to write for Ms., the magazine Steinem helped launch in 1972.

Prescient coverage

More than Friedan and NOW, Ms. magazine’s editors had revolutionary goals in mind. A spirited compilation, “50 Years of Ms.: The Best of the Pathfinding Magazine That Ignited a Revolution,” charts the publication’s evolution over the decades and highlights its prescient coverage of issues including abortion rights, domestic abuse, and sexual harassment. The article that kicks off the collection, “Click! The Housewife’s Moment of Truth,” begins, “American women are angry.” Sadly, many of the problems foregrounded in those early issues have not been solved five decades on.

Still, the collection, edited by Katherine Spillar and the magazine’s current editors, is one to savor. In addition to a well-balanced mix of reporting, fiction, poetry, and photography, the volume features reproductions of iconic covers and reader letters from girls and women of all ages, which form, in the editors’ words, “a rich tapestry of ‘Click!’ moments.” It includes a foreword by Steinem and contributions by Angela Davis, Barbara Ehrenreich, Rita Dove, Audre Lorde, Robin Morgan, Alan Alda, and many others.

Like NOW, Ms. had its struggles. But its behind-the-scenes conflicts, including accusations that it prioritized the concerns of white women, are not evident in this celebratory collection, which has been curated to emphasize diversity.

Ms. lives on as a quarterly magazine published by the nonprofit Feminist Majority Foundation. So too does NOW, even if the corporatized nonprofit with offices in Washington is quite different from the early days’ scrappy network of local chapters.

It’s hard to imagine either Ms. or NOW having the political, social, or cultural impact it once did. Still, their endurance both reassures and inspires.