Growing mighty: How a Jamaican author created a freer life

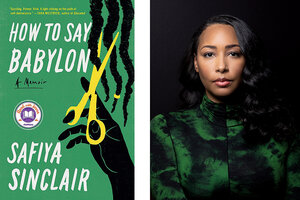

In a vivid and poetic memoir, Safiya Sinclair chronicles her journey from sheltered Rastafarian girl to a self-assured, award-winning poet and author.

Beowulf Sheehan/Simon & Schuster

At the outset of her searing memoir, “How to Say Babylon,” Safiya Sinclair writes that her upbringing in a strict Rastafarian household in Montego Bay, Jamaica, involved “[watching] the men in my family grow mighty while the women shrunk.” But Sinclair, an acclaimed poet, had too much fire and ambition to shrink. In lyrical prose, she recounts her father’s autocratic control over her and her mother and siblings, and she describes how poetry emboldened her to imagine a different life.

While Sinclair does not shy away from documenting her father’s brutality, she also seeks to understand how a parent she revered as a young girl became increasingly violent and tyrannical.

Her father, Djani, was born in 1962 and never knew his father. His mother became a devout Christian, while Djani found purpose in the strict tenets of Rastafarianism, a religion whose dreadlocked followers were pariahs in Jamaica even as adherents such as reggae musician Bob Marley were a major part of the country’s cultural identity. As a teenager, Djani was left to fend for himself. Djani achieved early fame in his teens as the lead singer of the reggae band Future Wind. But the group had imploded by the time he met Sinclair’s mother, Esther. Djani supported his growing family by begrudgingly performing the music of Marley and other reggae stars at tourist resorts.

Success eluded him in the outside world, but he insisted upon being worshipped at home. A Rastafari man, Sinclair writes, was considered “a living godhead, the king of his own secluded temple.” She and her siblings were subjected to sermons about the “sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people.” Rastafarians refer to these influences as “Babylon.”

An ascetic lifestyle was required to resist these forces. The family didn’t eat meat, dairy, or salt. Sinclair and her sisters, whose purity increasingly obsessed Djani, were forbidden from socializing and from wearing pants or shorts, jewelry, or makeup. As his career prospects dimmed, Djani’s moods became darker; his days, Sinclair writes, “were hushed with disappointment or torched with anger.” He beat the children for the slightest infraction.

While as a good Rasta wife, Esther never challenged her husband – “not once,” Sinclair marvels – she set about stitching the family back together when Djani went off to work. “My mother jolted to life again and did her best rebuilding work, weaving her cocoon around us,” Sinclair writes.

Esther gave Sinclair, at age 10, a book of poetry that became a lifeline. Sinclair began composing poetry, learning that “pain could be transformed into something beautiful.”

Sinclair was as ill at ease at her elite private school, which she attended on scholarship, as she was in her repressive household, but she excelled there. Her parents couldn’t afford to send her to college, so she spent six lonely years at home, reading, writing poetry, and waiting for her life to begin.

The author began submitting poems to the Jamaica Observer, and doors began to open. A scholarship to Bennington College in Vermont finally launched her from her father’s house. She eventually earned a Ph.D. in literature and creative writing and is now an English professor at Arizona State University. In the end, it is Sinclair who grew mighty.