President Lincoln has long provided wisdom. What can he offer today?

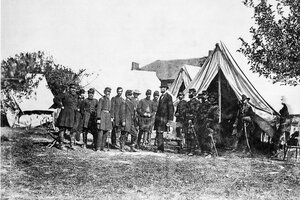

President Abraham Lincoln, wearing his trademark top hat, visits Union Army Gen. George McClellan (facing Lincoln) and his staff at Antietam, Maryland, in 1862, during the Civil War.

Alexander Gardner/AP/File

More than any other American president, Abraham Lincoln has been considered a source of wisdom for subsequent generations. New books on Lincoln reliably appear every February to coincide with Presidents Day, joining an already vast library.

This year brings two excellent studies of the 16th president that explicitly look to him for insight into questions currently besetting the American republic. Allen C. Guelzo’s “Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment” explores Lincoln’s vision of democratic government, while Harold Holzer’s “Brought Forth on This Continent: Abraham Lincoln and American Immigration” centers on Lincoln’s handling of an issue that was as divisive in the antebellum period as it is today.

Interestingly, there is little overlap between the two books. “Our Ancient Faith” is a slim, meditative volume whose primary focus is slavery and the Civil War. “Brought Forth on This Continent,” meanwhile, is a broad examination of immigration’s impact on 19th-century politics. Holzer notes that the subject has been neglected by historians precisely because of the overwhelming significance of race to the cataclysmic events of Lincoln’s time.

Why We Wrote This

In times of turmoil, Americans look to President Abraham Lincoln for wisdom. His experience guiding a divided nation offers insights, as well as hard-earned lessons.

Princeton University historian Guelzo, the author of more than a dozen books on Lincoln and his times, establishes at the outset that his latest is an explicit response to the dire state of American democracy. He writes in a brief preface that he has long “taken consolation” in Lincoln, “who gave democracy a new lease on life and a fresh sense of its purpose.” He continues, “To all those who have despaired of the future or whose lives have been ruined by the failures of the present, I offer this man’s example.”

The author proceeds to establish that both before and during his presidency, Lincoln’s actions were guided by his ardent faith in democracy, which he saw as, in Guelzo’s words, “the most natural, the most just, and the most enlightened form of human government.” (The book’s title comes from Lincoln’s reference to democracy as “my ancient faith.”) Only in a democracy, Lincoln observed, could somebody like him, formerly “a strange, friendless, uneducated, penniless boy,” aspire to reach the highest office in the land.

Guelzo notes that in his speeches and writings, Lincoln had more to say about what a democracy is not than about what it is. A country with masters and slaves, he insisted, fell short of a true democracy. Since childhood, Lincoln had believed that slavery was wrong. He was vocal in opposing the growing view in the South that slavery was not just a “necessary evil” but a “positive good.” In a speech before he became president, he noted acidly, “Although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself.”

Critics of Lincoln have often painted him not as a lover of democracy but as a tyrant, pointing to his suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War. Guelzo concedes that the wartime president did encroach on civil liberties by, among other things, arresting political dissenters and shutting down unfriendly newspapers. But as part of his vigorous defense of his subject from the “Lincoln-haters,” the author argues that while in some cases Lincoln strayed too far from democratic ideals, his temporary actions “were not civil cataclysms.” And he suggests that they pale next to Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, which the president believed would revitalize American democracy.

Finally, Guelzo reasons that we should be reassured by the fact that the United States has already weathered a period of extreme polarization. He confidently concludes that it is “comforting that these frustrations are not novelties, however much they feel like them, and that the American democracy has endured, risen, and surmounted them once, and will do so again.”

Like Guelzo, Holzer is a prolific Lincoln scholar. His latest book opens in 1863 with the president urging Congress to establish “a system for the encouragement of immigration.” Nearly 10 million Europeans had arrived on American shores between 1830 and the start of the Civil War, but the conflict had slowed the tide. Lincoln, who called immigration a “source of national wealth and strength,” wanted the government to take active measures to attract foreigners to fill war-related labor shortages in agriculture and industry.

As the author demonstrates, however, many of Lincoln’s fellow citizens did not share his positive view of immigration. In fact, early in his political career, Lincoln’s Whig Party was home to a vocal nativist, anti-Catholic faction. “Not all Whigs were nativists,” Holzer explains, “but nearly all nativists were Whigs.” Lincoln did not belong to this intolerant sect. But he did refrain from publicly rebuking the nativists, as he feared driving them out of the party.

Holzer deftly summarizes the complicated politics of the antebellum period, including the rise of the secretive, nativist Know-Nothing movement, the collapse of the Whigs, and the formation of the anti-slavery Republican Party. (Lincoln was the first Republican to be elected president.) While the pro-slavery Democratic Party, favored by Irish Americans, warned its Irish voters that Lincoln’s party would prioritize Black people over foreign-born white citizens, the Republicans attracted German immigrants who were generally strong supporters of abolition.

German and Irish immigrants became the two largest foreign-born contingents fighting for the Union side when war broke out, with 175,000 German men and 150,000 Irish men enlisting. With soldiers from Poland, Italy, Switzerland, and elsewhere, Holzer calls the war a “multiethnic crusade.” (Lincoln only permitted Black men to enlist after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863.)

According to the author, Irish soldiers were committed to the Union side “as long as federal war goals remained fixed on defending the Constitution and the flag and restoring the Union, not on eradicating slavery.” Ironically, the Lincoln who promoted European immigration came close to losing reelection in part because of lack of support from both Irish and German voters; Irish Americans had long opposed emancipation, fearing that freed African Americans would compete with them for low-paying jobs, while German Americans faulted the president for moving too slowly to free those who were enslaved.

Both authors are admiring of their subject, but not unreservedly so. Guelzo notes that Lincoln did not support political and social equality between Black and white people and that he “can be judged too passive and acquiescent in the racism all around him.” In a similar vein, Holzer observes that Lincoln was unsympathetic toward Native Americans and that his expansive view of immigration largely excluded those from Asia and Spanish America.

The authors seem to disagree on one particular point, however. In considering Lincoln’s increasingly progressive policy stances, Holzer argues that the 16th president “evolved on immigration, just as he would evolve on the issue of Black freedom and rights.” Guelzo, for his part, rejects the idea that Lincoln significantly transformed during his lifetime, referring to “useless tropes like growth or evolution to argue that, over time, Lincoln changed for the better.” Guelzo instead sides with historians who believe that Lincoln’s character remained consistent – that shifts in external conditions, more than any internal conversion, enabled his most righteous achievements.

If nothing else, such scholarly debates should help ensure a steady stream of Lincoln books for years to come.