Scoundrels, as well as heroes, shaped America’s founding

Two historians tackle the daunting task of giving Benedict Arnold and Aaron Burr – two of America’s most infamous villains – more nuanced portraits.

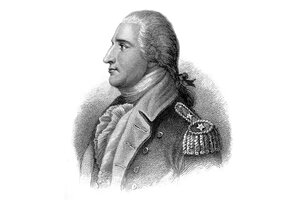

Benedict Arnold’s profile is captured in an engraving by H.B. Hall, from a painting by John Trumbull, published in 1879.

National Archives and Records Administration

America’s founders are revered figures, but in recent decades scholars have sought to present a fuller picture of men like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton, exploring their blind spots and flaws in addition to their achievements.

Two new books suggest that the founding era’s villains, like its heroes, ought to receive more nuanced consideration, too.

Benedict Arnold, the patriot hero who defected to the British in the midst of the Revolutionary War, is remembered as the foremost fiend of his time: His name is practically synonymous with treason. Jack Kelly’s vivid and fast-paced biography, “God Save Benedict Arnold: The True Story of America’s Most Hated Man,” strives for a balanced view, focusing on Arnold’s contributions to independence before turning to his betrayal.

Not surprisingly, Arnold also rates a chapter in “A Republic of Scoundrels: The Schemers, Intriguers & Adventurers Who Created a New American Nation,” an entertaining anthology edited by historians David Head and Timothy C. Hemmis. Hemmis observes that despite an “official culture” that emphasized “public virtue and self-sacrifice as the lifeblood of a republic,” an assortment of duplicitous characters exploited the young nation’s instability in order to amass wealth and power for themselves.

Shifting allegiances

Kelly’s biography portrays Benedict Arnold as a bold man of action who was vital to the Revolution. Born in Connecticut in 1741, he was a fifth-generation American with several prosperous businesses when war broke out. Though the family’s lineage was impressive, Arnold’s father had failed as a business owner. Deeply affected by his father’s ruin, Kelly writes, Arnold “had always felt an irresistible urge, almost a mania, to climb, to acquire, to become somebody.”

That urge was reflected in his belief in aggressive action to defeat the British. Between 1775 and 1777, Arnold played a key role in several important campaigns: the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, the unsuccessful invasion of Quebec, the Battle of Valcour Island, and the Battles of Saratoga. Kelly’s narrative includes gripping accounts of these military operations.

While Arnold exhibited a “fearless calm” in battle, off the field he was prickly and sensitive to slights. He had the trust of George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, but his antagonistic personality earned him enemies and led to attacks on his reputation. Much to Washington’s dismay, the Continental Congress, which made all decisions regarding officers’ commissions, repeatedly declined to promote Arnold, even promoting men of lower rank above him. He had fought valiantly, sustaining serious injuries to his leg in both Quebec and Saratoga, but Congress was guided more by politics than by military merit.

By 1780, when the war was dragging and morale was low, Arnold was serving as commander of New York’s lower Hudson region, which included the military fortification at West Point. Arnold conspired to surrender the strategically valuable fort to the British; if his plot hadn’t been discovered, it could have devastated the patriot cause. “Arnold has betrayed us,” Washington lamented when presented with evidence of the treachery. “Whom can we trust now?”

Arnold, who went on to fight for the British, claimed that he had switched sides in an effort to reconcile the two factions and help bring an end to the war. Hamilton attributed his treason to “the ingratitude he had experienced from his countrymen.” Because Arnold was paid handsomely for transferring allegiances, most of his contemporaries chalked up his actions to simple greed.

Kelly – who tells the story skillfully even if he doesn’t cover new ground – ventures his own theory. It’s rooted in Arnold’s need for action, which had been frustrated by his injuries. “Disabled from sharing in the transcendence of battle, he may have searched for a way to live amidst danger and intrigue, and to play a role in great events,” the author speculates, acknowledging that Arnold’s motives will never be fully known.

Corruption and greed

Writing about Arnold in the “Scoundrels” anthology, contributor James Kirby Martin goes even easier on America’s archvillain. His essay catalogs Arnold’s unfair treatment at the hands of military and civilian leaders, concluding that “the Revolutionaries did not represent one big, happy family, but a quarrelsome bunch that helped turn Arnold into a likeness of them.” He comes perilously close to denying Arnold’s agency, writing, “Circumstances morphed this heroic fighter into a historical pariah.”

Not everyone profiled in “Scoundrels” is let off the hook. Besides Arnold, the book’s other familiar figure is Aaron Burr. While Burr is remembered for killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel, Hemmis’ entry describes a less well-known episode: the opportunistic former vice president’s alleged attempt to establish an independent country in the western territory, which he would lead. Burr was charged with treason and acquitted in 1807; his full intentions, while apparently malevolent, remain unclear.

Most of the book’s figures have faded into obscurity. But soldier and diplomat James Wilkinson, the subject of an essay by Samuel Watson, seemed to pop up everywhere in his day. He badmouthed Arnold while serving under him during the war, and he was involved with Burr’s conspiracy before turning on him and informing President Jefferson of Burr’s plans to raise an army of frontier fighters. After Wilkinson’s death, it was discovered that he’d been a paid agent for Spain. Watson calls him “the most morally flexible man in the world.”

Another chapter focuses on William Blount, who, while serving as a senator from Tennessee, was the first federal official to be impeached. Prior to that, he used his position as governor of the Southwest Territory to amass 2 million acres of land, cheating veterans and Native Americans in the process. He was, in the words of contributor Christopher Magra, “a scoundrel through and through.”

Co-editor Head makes a compelling point that he acknowledges is “so obvious it is easy to miss”: Building a new nation was a huge and multifaceted endeavor, requiring “not only a handful of demi-gods with names like Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton, but a host of mere mortals, many of whom were out for themselves.” These scoundrels are part of our founding story, too.