He invented a midcentury modern chair that defies space – and time

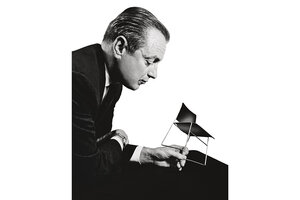

David Rowland holds a model of his chair design in 1964.

Photos from Commercial Furniture Group/Howe A/S Phaidon Press

Is it possible to design a revolutionary new chair? David Rowland did. You’ve most likely sat on it.

The industrial designer’s signature chair, the 40/4, is the world’s first compactly stackable chair. You can stack 40 of them at a height of just 4 feet. Singly, they can fill a room. Then they can be packed up into a tiny storage space.

Rowland’s chair debuted in 1964. That year, it won the grand prize at the Triennale di Milano, the annual exhibition mecca for art and design. Since then, the 40/4 has become part of many permanent collections, including at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Musée D’Orsay in Paris. But it’s no museum piece. Many examples of midcentury modern furniture now look very much “of their time.” By contrast, the 40/4 seems timeless. It looks equally at home inside a modern office or at the ancient edifice of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Why We Wrote This

A good idea can take years to come to fruition. A midcentury modern designer found that persistence and continual refinement were needed to move his creation from concept to reality.

Rowland said the 40/4 fulfilled his goal to “create the most universal chair ever built with the least expenditure of materials and labor.”

The design book “David Rowland: 40/4 Chair” chronicles the creative, logistical, and institutional challenges that the midcentury modern designer faced to make his idea a reality. It’s a story of tenacity. More than that, it’s a manifesto for the creative principles Rowland espoused. He was an advocate for sustainability long before the concept became popular. The designer railed against mass-produced products if they weren’t “meaningfully necessary.” He also called for purposeful design aimed at solving the world’s problems.

As Rowland once put it, “the different is seldom better, but the better is always different.”

Those words are also an apt description for the man who said them. This beautifully illustrated monograph, eloquently co-written by Rowland’s widow, Erwin, and journalist Laura Schenone, is a detailed portrait of the nonconformist entrepreneur.

During his lifetime, Rowland designed everything from ahead-of-their-time houses made out of shipping containers to a safety ashtray. (A devout Christian Scientist, Rowland didn’t smoke.) While studying for his Master of Fine Arts in design at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, he submitted a drawing of a vehicle to the Packard Motor Car Co. It included a gas cap hidden beneath the license plate. When the company implemented that idea without acknowledging Rowland’s blueprint, let alone paying him, he wasn’t resentful. “There are more ideas where that one came from,” he said.

Whenever Rowland picked up his draftsman’s pen, he prayed for ideas. As a 21-year-old pilot of a B-17 during World War II, he’d credited prayer for a safe landing after enemy fire crippled two of the bomber’s engines. A few years later, Rowland turned to God during a low point. For years, the freelance designer had been visiting legendary furniture designer Florence Knoll to show her prototype chairs he’d created. She kept turning down his pitches. The thought came to him, “Why don’t you see how many chairs you can get into the smallest space?”

Instead of trying to appeal to Knoll’s taste, he aimed to redefine the chair so as to fulfill a need. Rowland first learned the importance of purposeful creation back in 1940. Then a high school student, he’d received special permission to enroll in a college summer course taught by László Moholy-Nagy. The Hungarian was a key figure in Germany’s Bauhaus school of design. (The book includes delightful accounts of Rowland’s encounters with many other 20th-century art and design luminaries, including Charles Eames, Buckminster Fuller, and Norman Rockwell.) Like other Bauhaus exiles who’d fled Nazi Germany, Moholy-Nagy exported the school’s philosophy to America.

“Bauhaus teachers saw the threat of dehumanization in the rapid rise of industrialism,” the authors write. “They advocated for human creativity and imagination and wanted to educate artists across creative disciplines to work with industry to create a better world.”

Those principles were a sharp break from trends of the time. According to the authors, eminent industrial designers such as Raymond Loewy often focused primarily on aesthetic appeal. They wanted products to stand out on the shelf. Why own a steam iron that resembles a warmed-up horseshoe when you could own one that emulates the futuristic sleekness of a spaceship? Rowland opposed style for its own sake. In a 1968 speech titled “The Moral Basis of Design,” delivered to 3,000 people at a Smithsonian exhibition about the history of chairs, he explained that beauty emerges organically from a design that fulfills its purpose.

Rowland’s chair features elegant curves. But to shape the seat, he had to overcome numerous challenges. Usually, the only way to stack any item is for each consecutive unit to be slightly larger than its predecessor. The marvel of the 40/4 is that each chair is the same size and proportion. Yet they slot together. It appears to defy the logical limits of spatial dimension. Both the seat and the back are set within the frames, rather than on top of them, so that they don’t bulge outward and create bulk when piled atop each other.

When Rowland presented his latest chair to Knoll, he said nothing about what made it a breakthrough product. Instead, he had her sit on two prototypes stacked on top of one another. They were so slim that they appeared to be a single chair. Then he revealed that she’d actually been sitting on two stackable chairs. Ms. Knoll’s reaction was immediate: “We’ll take it.”

They didn’t. Without explanation, Knoll Associates prematurely canceled a contract for the 40/4. Other furniture companies, including Herman Miller, couldn’t see a use for it, either.

“It takes time for consumers to catch up and embrace what is different, because it is unfamiliar,” the authors write.

Rowland spent years in the wilderness trying to bring his invention to the market. Eventually, he learned through an architectural firm that the University of Illinois needing 17,000 chairs for new campus buildings. The architects loved his design, and connected him with the General Fireproofing Company, a manufacturer of school and office furniture. General Fireproofing had the capacity to manufacture the 40/4 chair at scale.

Rowland’s masterpiece has since sold in the millions. Yet he isn’t as well known today as some of his midcentury modern peers. Perhaps it’s because he ultimately had to work outside of an established system of design and furniture institutions.

“David Rowland: 40/4 Chair” may help boost his name recognition. It also reminds contemporary designers of timeless principles that serve as a valuable North Star.