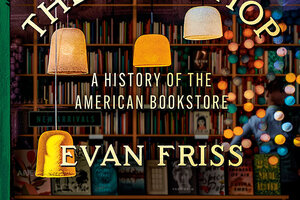

How bookstores became cornerstones of American culture

In a riveting history, Evan Friss digs into how U.S. bookstores shaped everything from the American Revolution to banks being open on Saturdays.

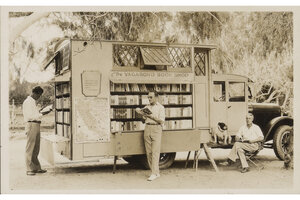

The Vagabond Book Shop was built from an REO Speed Wagon, a type of truck, and had space for over 1,000 books.

James D Phelan Photograph Albums/Bancroft Library/University of California, Berkeley

To paraphrase Mark Twain, the reports of the death of independent bookstores are greatly exaggerated.

In “The Bookshop: A History of the American Bookstore,” Evan Friss describes how these meccas to the printed word have defied similar predictions throughout the decades. Not only have they survived, but also they have shaped American culture, influenced retail trends, and even helped usher in Saturday banking hours.

Friss, a history professor, explores the parallel paths of American history and the bookstore with a thorough and objective eye. (Find our Q&A with him here.) He focuses on 13 different bookshops from the Colonial era to the present day. These include familiar franchises, such as B. Dalton and Barnes & Noble, as well as small independents, including Parnassus, a store in Nashville, Tennessee, owned by bestselling author Ann Patchett.

Friss shows how these enterprises reflect the country’s identity. The book is a fascinating work that underscores the importance of these beloved, if perpetually financially strapped, institutions.

Friss begins with a Founding Father who was in the publishing business before the word “bookseller” entered common use – Benjamin Franklin. A printer by trade, Franklin had a small retail market; records indicate that only about 35% of Colonial households even owned a book. Still, the Philadelphia patriot credited an increase in reading as the impetus behind the American Revolution: The Stamp Act of 1765, a tax imposed by the British Crown on all printed material in the Colonies, lit the match for the Revolutionary War.

One could argue that books emerged as part of America’s DNA.

In subsequent chapters, Friss explores the shifting role of bookstores and how each shop emerged as an expression of its era.

For example, in the first decades of the 20th century, New York City included a financial district, a theater district, and – for a time – a bookstore district. Bookseller’s Row on Fourth Avenue in downtown Manhattan included the renowned Strand bookstore, which has been in business since 1927. The success of this district prompted a local bank to add Saturday hours to make cash available to shoppers who were scooping up new releases as well as secondhand copies. Friss tells how customers, mostly men, ran “the gamut from ‘improper bohemians’ to ‘staid bankers.’”

Later, as booksellers began creating spaces to linger and discuss ideas, bookstores emerged as centers of not only culture but also activism. These businesses expanded beyond their role as hubs of commerce. In fact, they fueled and fostered social movements.

“The ubiquitous image of the quaint bookshop and the becardiganed bookseller makes us blind to their power,” Friss writes. “The right book put in the right hands at the right time could change the course of a life or many lives.”

The influence that bookstores exerted was not benign in all cases. The Aryan Bookstore in Los Angeles, which opened in 1933, emerged as the center of American Nazism. It was shut down by government authorities after the United States declared war on Germany and entered World War II.

Enterprises with more pro-social goals included the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York’s Greenwich Village, which opened in 1967 with the intention of changing public perceptions of gay people, and Drum & Spear in Washington, a Black-owned bookshop that opened during the volatile summer of 1968 expressly to stock books by Black authors.

Friss explains how such stores provided readers with books that explained the histories of minorities and marginalized populations while also providing practical support to members of these communities. The Oscar Wilde, for example, maintained a telephone hotline to connect members of the gay community with information and services, a rare commodity for the time. In the case of the nonprofit Drum & Spear, the author notes that the very existence of the store refuted racist stereotypes of Black people. “They had sat at lunch counters. They had marched in the streets. Now they would sell books.”

Drum & Spear proved to be a constructive response to a challenging era. America is again in the midst of social upheaval. Yet Friss shares how booksellers such as Patchett have embraced the mission as a cultural imperative. This commitment, as well as the enduring contributions of American bookstores, offers reasons for hope.