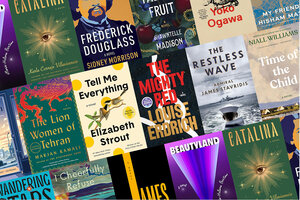

A year of plentiful prose: The best books of 2024

Fiction

James, by Percival Everett

“With my pencil, I wrote myself into being,” asserts James in Percival Everett’s National Book Award-winning novel. This is Jim of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” fame, now at the helm of the story. A self-educated man, James confronts a vivid cast of ne’er-do-wells, enslavers, and fellow escapees as he wends his way north in the hopes of buying his family’s freedom. It’s a gripping tale of reinvention and determination.

The Mighty Red, by Louise Erdrich

Why We Wrote This

We asked our reviewers to choose the books that captured their imaginations this year. They came back with thoughtful and eclectic titles that speak to our common humanity.

From the masterful Louise Erdrich comes the story of a North Dakota farming community whipsawed by crises. At the book’s center is Kismet, a high school graduate who gets pulled into a questionable marriage, and her truck-driving, devoted mother. The tale’s many threads pull together into a rewarding portrait of renewal and honesty.

Frederick Douglass, by Sidney Morrison

Frederick Douglass roars from the pages of this meticulous novel, thanks to the voices of his steadfast wife, Anna, and their children, plus confidants, paramours, and even enslavers. A complex man emerges. Proud and persistent, fickle and flawed, he’s inseparable from the era’s tumult and hard-fought triumphs.

Tell Me Everything, by Elizabeth Strout

Elizabeth Strout’s warmhearted novel brings together her best-loved characters, including Olive Kitteridge, Bob Burgess, and Lucy Barton, in the fictional town of Crosby, Maine. “Tell Me Everything” is about how stories about others’ lives – and how really listening – help us understand and connect.

The Fallen Fruit, by Shawntelle Madison

Since the late 1700s, the Bridge farm in Virginia has offered a haven for its freeborn Black owners. But there’s a caveat: A child born to each Bridge man will fall back in time. As the novel opens, Cecily, a mother in 1964, begins investigating her ancestors’ time-traveling troubles. It’s an engaging take on freedom and free will.

I Cheerfully Refuse, by Leif Enger

In a rickety sailboat on storm-tossed Lake Superior, a grieving musician flees a powerful enemy. Set in a speculative future in which the supply chain has failed and a lethal drug holds sway, Leif Enger’s latest novel steers a harrowing course through a broken world. Yes, it’s grim, but in Enger’s capable hands it’s also a riveting story of resilience.

Time of the Child, by Niall Williams

Niall Williams’ novel returns to the Irish village of Faha during Christmas 1962. When an abandoned infant is brought to the local doctor on a cold, wet night, it leads to a situation that proves transformative for the widower and his solitary eldest daughter. And it marks a subtle turning point in a community ruled by the twin authorities of church and state.

The Lion Women of Tehran, by Marjan Kamali

Fierce women fill the pages of Marjan Kamali’s engrossing tale of friendship, class, betrayal, and politics in Iran. Ellie is a smart, lonely girl desperate for a sense of family after the death of her father. Zesty, optimistic Homa would rather study to be a lawyer than attract the attentions of a future husband. As girls in 1950s Tehran, the two forge a bond that’s tested over decades.

Come to the Window, by Howard Norman

War overseas. Pandemic fears. A shocking scandal. Attacks on “the other.” Howard Norman’s gem of a novel unfolds not in the recent past, but in Nova Scotia in 1918. Indelible characters, taut prose, deft pacing, and resonant questions about bearing witness make this a winner.

The Restless Wave, by Admiral James Stavridis USN (Ret.)

Former NATO Commander and four-star Adm. James Stavridis creates a gripping novel about a young Navy officer tested during the early sea battles of World War II, from Pearl Harbor to Midway and Guadalcanal. The novel is action-packed, and filled with insights into leadership and courage.

Mina’s Matchbox, by Yoko Ogawa, translated by Stephen B. Snyder

Yoko Ogawa’s gemlike novel is a coming-of-age story about 12-year-old Tomoko, who goes to live for a year with her delightful cousin Mina and her family. The girls become kindred spirits, sharing secrets, wonderment, and several key world events. Ogawa’s storytelling is radiant.

Wandering Stars, by Tommy Orange

Tommy Orange weaves a fictional Cheyenne family into such real-life events as the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, dramatizing the impact of historical events on subsequent generations of Native Americans. “Wandering Stars” is the engaging follow-up to his award-winning first novel, “There There.”

Catalina, by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

Catalina Ituralde is navigating her senior year at Harvard amid fears of deportation and dreams of love, fame, and literature. This lovely debut novel explores the immigrant experience through the lens of an ambitious, funny, smart, and sometimes fragile young woman.

Beautyland, by Marie-Helene Bertino

Adina, a human-looking alien growing up in 1980s Philadelphia, adores astronomer Carl Sagan. “He is looking for us!” she enthuses to her otherworldly superiors in one of many life-on-Earth dispatches. Adina navigates human childhood while her single mother, unaware of her daughter’s true identity, struggles to keep them afloat.

My Friends, by Hisham Matar

A teenager leaves his cherished family in Libya to pursue higher education at the University of Edinburgh. Protesting against the Qaddafi regime results in exile from his homeland. Hisham Matar provides insights into life under revolution and in exile.

Sipsworth, by Simon Van Booy

In this charming novel about an English widow whose life is slowly awakened by a stray mouse, novelist Simon Van Booy reaffirms his talent as a master prose stylist. The themes, which include the pain of loneliness and the redeeming power of community, resonate. But in his story about serendipity, Van Booy has given us a tale that is, in its larger dimensions, truly timeless.

Nonfiction

An Unfinished Love Story, by Doris Kearns Goodwin

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin was married for more than 40 years to Dick Goodwin, a speechwriter and adviser to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. In the years before Mr. Goodwin’s death, the couple went through hundreds of boxes of his memorabilia from those administrations. This affecting book, blending history, memoir, and biography, is a personal account of a pivotal

era.

Paris in Ruins, by Sebastian Smee

Impressionism emerged in late-1860s Paris. But the movement took off only after the horrors of the Franco-Prussian War drove artists to create works focused on the impermanence of life. This deeply researched and well-written book combines art and biography with political and military history to shed fresh light on the origins of this seminal period in modern art.

The Light Eaters, by Zoë Schlanger

Atlantic staff writer Zoë Schlanger debuts with an exploration of the new science of plant intelligence. In elegant prose and with a sense of awe, she describes plants’ remarkable adaptive techniques, communicative abilities, and social behaviors.

Bringing Ben Home, by Barbara Bradley Hagerty

Ben Spencer was wrongfully convicted of murder in Dallas in 1987. This compelling book tells the story of his flawed trial, the barriers built into the Texas legal system that made it nearly impossible to get the decision overturned, and how he and a small group of supporters worked to secure his release. Barbara Bradley Hagerty has written a true-crime story that reads like a legal thriller and, at same time, recounts the systemic failures of the judicial system. It is eye-opening, discouraging, and inspiring.

Audubon as Artist, by Roberta Olson

Much has been written about bird artist John James Audubon as an American original. In “Audubon as Artist,” Roberta Olson harnesses her insights as a museum curator to reveal the European traditions that informed Audubon’s art. Drawing on masters as varied as Rembrandt and David, this richly illustrated survey explores Audubon as one of the great dramatists of the natural world, one whose complicated legacy is still shaping our debates about conservation.

Our Kindred Creatures, by Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy

This fascinating history traces the shift in American attitudes toward animals in the decades after the Civil War. The authors describe the era’s widespread mistreatment of animals and profile the activists who convinced their fellow citizens that the prevention of animal suffering was a just cause.

John Lewis: A Life, by David Greenberg

This rich biography spans the civil rights icon’s rural Alabama childhood, his pivotal role in the student movement to desegregate the South, and his service in Congress. Drawing on archival materials and interviews with John Lewis and more than 250 people who knew him, David Greenberg leaves no doubt as to his subject’s heroism.

Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here, by Jonathan Blitzer

Jonathan Blitzer traces the roots of the immigration crisis back to what he terms America’s misguided Cold War-era interventions in El Salvador and Guatemala. The author’s powerful, compassionate account highlights individual stories, creating an epic portrayal of migration’s human stakes.

The Bookshop, by Evan Friss

Evan Friss explores how American bookstores have helped shape the nation’s culture, from social movements to retail trends. Although the demise of small indie bookstores has long been forecast, devoted shop owners continue to defy this prediction.

Custodians of Wonder, by Eliot Stein

While society is quick to celebrate the first person to achieve something, Eliot Stein notes that we rarely honor the last. He travels to five continents to share the stories of 10 artisans practicing ancient crafts – a rare type of pasta, a grass-woven bridge, soy sauce brewed from the original 700-year-old recipe – and asks what we might lose if these custodians prove to be the last.