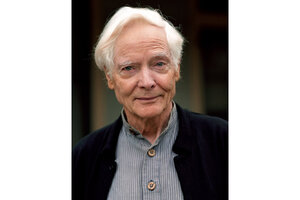

W.S. Merwin: What kind of poet laureate will he be?

As poet laureate, W.S. Merwin is assuming a role with changing expectations.

W.S. Merwin is the new poet laureate of the United States.

Matt Valentine/LIbrary of Congress

When news broke Thursday that W.S. Merwin had been named poet laureate of the United States, many poets had two reactions. The first was “Good for him. He’s a wonderful writer who deserves recognition.” The second was, “I was hoping for another Pinsky who would really advance the cause.”

That dichotomy reveals a great deal about the poetry world and how expectations have changed about the writers who serve as the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, the position’s official title.

Each laureate is supposed to promote a greater consciousness of and appreciation for the art form. Yet in reality, some have acted like ceremonial monarchs while others have been vigorous ambassadors/promoters. Robert Pinsky, the most effective laureate to date, had the zeal of an activist and the charisma of a celebrity. The George Clooney of the poetry world, if you will.

W.S. Merwin, who is now in his 80s, may have ambitious plans that he hasn’t yet revealed. (He’ll be interviewed on NPR Friday night.) But if that’s not the case, his potential to influence writers and the public shouldn’t be dismissed.

After all, Merwin has lived his activism for most of his distinguished career. That’s obvious in his writing, which has evolved, over time, from tight imagistic poems to sprawling pieces that lack punctuation to his more recent work, which uses everyday experiences – walking with his dogs, remembering his father – to explore complex metaphysical concepts. Each shift required boldness of thought and the willingness to take big risks.

Merwin’s activism didn’t stay on the page, though. When he won his first Pulitzer Prize in 1970, he gave away the prize money to protest the Vietnam War. That decision cost him the support of W.H. Auden, who had chosen Merwin’s first book for the Yale Series of Younger Poets.

A few years later, Merwin bought an old plantation in Maui, where he still lives, and began restoring the land. Those efforts demonstrate a deep commitment to the natural world, which is reflected in his writing. Merwin was “green” before green became popular.

Many poets could benefit from his example of pairing words with actions. Or from treating people with great dignity and respect, even when there’s no clear advantage in doing so. I say that because I have vivid memories of hearing him read in Cambridge, Mass., years ago. I had recently earned my MFA, and I was eager to tell him how much his early work had influenced me and the way I approached writing. He listened intently, as if I were as important as the people who were buying his new book and raving about his recent poems.

Several years later, when I was a staff writer for the Monitor, I interviewed Merwin by phone. The time difference meant that he was speaking with me late at night, but he didn’t sound the least bit irritated by the inconvenience. His comments were insightful, thought-provoking, and genuine. He wasn’t just going through the motions, as frequently interviewed authors sometimes do.

That quality still impresses me because it’s the antithesis of what one sometimes sees in the poetry world, where a sharp tongue and withering comments are often considered the fastest way to become known and respected.

I hope Merwin’s appointment gives him an opportunity to share some important lessons about aesthetics and true activism. Witnessing on the page just isn’t enough.

Elizabeth Lund regularly reviews poetry for the Monitor.

Must the poet laureate be an activist? Join the Monitor's book discussion on Facebook and Twitter.