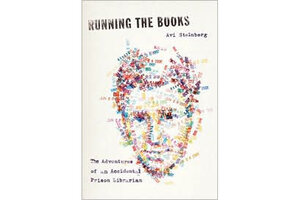

"Running the Books": Avi Steinberg talks about life as a prison librarian

Memoirist Avi Steinberg reflects on the humor, sadness, scariness, and "just utter strangeness" of working in a prison.

Avi Steinberg, a former yeshiva student and Harvard graduate, was working as a freelance obituary writer when he saw an ad for a full-time job with health benefits. The posting was for a prison librarian at the Suffolk County House of Correction in Massachusetts. Steinberg sent in his résumé, and then spent the next 2-1/2 years at “the Bay,” as both a librarian and a teacher of creative writing classes to inmates.

His new memoir, Running the Books, explores the role of the library in a prison and offers vividly drawn portraits of those who work and read there. There's the pimp who's writing his memoirs and the inmate who memorizes Shakespeare to get through solitary confinement. And then there's the former library patron who holds up Steinberg at knife point in a park, before recognizing him as “the book guy.”

Steinberg spoke with the Monitor via phone to discuss his path from yeshiva to prison.

Where did you get more of an education – Harvard or “the Bay”?

I think it was both. I think that it would have been a shame to do one without the other.... I came into the prison in many ways cognizant of the fact that this was another step in my education. It was a time when many of my friends were considering grad school, and were going to further their education in a variety of ways. I felt like I needed to do that in some way, too, but I didn't really want to go to a regular school and I wasn't really interested in the usual track. I did feel like something was missing in my education. I think it was both and I think it was the synergy between the two which I thought was, for me at least, a creative one.

And, by the way, I would add also yeshiva.... These places are very different from each other, and yet it's the tension that's created between these educational settings ... that I felt that, for me, was highly educational.

The one thing that was the common thread between these three places – Harvard, yeshiva, and prison – is that I spent time in libraries in all three. And I felt like that, to me, made sense. It gave me a sort of a holding place, some kind of commonality between these three places. And libraries end up being similar types of places wherever they are, and so they were different enough but also similar enough that there was some kind of continuity.

What would you say is the biggest difference between a prison library and a public library?

There's a much more communal sense around the prison library. It's like a community center.… People come there, not just for books, not just to get resources, and not even just to sit, but really to gather, to see other people, to feel there's some kind of continuity in their day....

What people read there and how it affects people's lives is very interesting and very important. But what's even more important is the conversations that happen around those books. The books literally create a space where people come together and tell their stories and share their own life experiences. You know, it's sort of like a live book. It's sort of like a book in real-time.... The drama happening in front of the bookshelves is as important as the drama in the bookshelves.

What were the most requested books, and were there differences in what male and female inmates requested?

The most popular genres were books on astrology and real estate.… I mention in the book that books on dream interpretation were often requested. This intrigued me – because of my yeshiva background, I always have the Torah and the ancient rabbinic texts in my mind. And of course, I remember that Joseph, who in the Bible was thrown into prison, becomes a dream interpreter.... So, I thought, there may be something about prison that lends itself to this desire for dream interpretation. As I described it, it's an “ancient prison literary genre.”

But mostly people asked for what they called “street books,” which end up being basically urban, black, pulp romance novels, largely by small publishers that are small, but growing rapidly, like Triple Crown Publications. These are very readable, kind of salty novels that speak to the daily lives of black people in the city.… Triple Crown Publications, for example, was founded by some people who had been in prison and then went out and basically fed this entire market that had been untapped, and now the books are coming back into prison. So it's interesting that there's this back and forth between prison culture and the city.…

The most commonly requested book was “The 48 Laws of Power,” by Robert Green, which is this sort of Machiavellian self-help book. We did not offer that book.

In terms of the differences between men and women? The women were better readers – it's just like the outside world.... The way women read in prison was interesting, because it related to the culture of women in prison. That is a hyper-, hypersocial group think. The men tend to be more solitary, and women are very much a group unit. And so, you have these crazes among the women for certain books. For two or three weeks, everyone wanted X book. One of those books was “The Diary of Anne Frank” – for three weeks, maybe a month, everyone wanted to read this book. I had to get extras in. Another time, it was Frida Kahlo. Everyone wanted to see art books of her paintings.

I was very interested in the tension created when your love for the written word conflicted with your job. For example, the notes that were called "kites” that were slipped into books for other inmates to find that you were supposed to be searching out and destroying.

It definitely was a conflict. You know, when you work in a prison, you end up coming up with all kinds of compromises, little compromises every day. And sometimes those compromises don't even totally make sense, but they're sort of psychologically necessary. So for example, with the kites, my job was search and destroy, to get rid of these kites, and there was good reason for that, too. It was in my interest to be in charge of the space. But at the same time, I kind of made one of these irrational compromises that I wasn't going to throw them out.… I wanted to respect the effort that someone had made. In some cases, someone had sat down and written a long letter by hand, and I wanted to respect that by not throwing it in the garbage, and yet I wouldn't deliver it.

One of the most moving stories in the book is that of Jessica, the woman you were trying to help reconnect with her son, who had also been sent to the same prison. Could you talk a little about her?

Jessica was a woman who came to class basically to sit next to the window, which was up in the prison tower.... And she sat by the window and stared into the prison yard down below. And that's why she came to my class. It turned out the reason she wanted to be there was that she wanted to see her son, who was a young inmate – maybe 18 years old, maybe even a little younger. She hadn't seen him for many years; she had abandoned him years earlier. All of a sudden, here they are reunited – not exactly reunited, but she had an inkling he was in there and she saw him. I was very, very struck by her desire to just sit and look at him....

She had in many ways a very hard and disappointing life, but this was the major disappointment of her life. And here it was, living in the same building as she was, and she was forced to confront it, and she tried to figure out how to work with that, but, as I described in the book, it didn't quite work out for her.

In the beginning of the book, you're robbed at knife point by one of your former clients.

So, this was Jamaica Plain, and I'd been to a movie that night, and this guy came up behind me and mugged me. And as he was taking my money, he recognized me from the prison. And he said, “Do you work at the Bay?” And I didn't know how to answer that question, so I said, "Yeah, I work in the library." And he said, “Oh yeah, I remember you – the book guy.”

I couldn't recognize him, because he was wearing a mask. And he did not give me my money back, and he said he still owes us two books. So, it was kind of funny, kind of sad, and kind of crazy and so, something about that whole simultaneous humor and sadness and scariness and just utter strangeness of that experience encapsulated a lot of the feelings of working in a prison.

I try to tell the story in a funny way. I don't think humor makes light of things; I think it's an important perspective on serious things. I think humor is very serious. I hope the humor doesn't come across as light-hearted. It's just a way of understanding a complicated reality.

Prisons on a moment-to-moment level are often very funny. Because people are bored, so they just sit around entertaining each other. They want to make each other laugh.… And yet there's ultimately nothing funny about a prison. It's a very sad and difficult and horrible place.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews books for the Monitor.