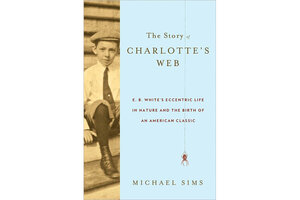

Editor's choice: The Story of Charlotte's Web

How E.B. White wrote one of the most successful books in the history of children’s literature.

The Story of Charlotte’s Web:

E.B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic

By Michael Sims

Walker & Co.

307 pp.

For every reader who grew up adoring the E.B. White classic “Charlotte’s Web” (and is there really a reader among us who did not?), this summer holds a treat in store. The Story of Charlotte’s Web by Michael Sims retraces White’s path in writing the book and, in so doing, helps us to understand how so truly “artless” a work of art was created.

Elwyn White was a shy and anxious child – a skinny boy with big ears and lots of allergies. Although doted on by a large and affluent clan, he always felt most comfortable in the family’s suburban barn, spending his time with the animals.

Although he seemed to glide effortlessly from his Ivy League education (Cornell University) to a successful perch at a trendy new magazine (The New Yorker), even as an adult, “Andy” (as he was known from college onward) continued to struggle with uncomfortable self doubts. (“He goes his way with too cautious a stride,” he wrote of himself in a sonnet that listed his own faults. “Frustration tickles his most plaintive strings.”) And despite the considerable acclaim he earned for his New Yorker pieces, he was frequently besieged by feelings of failure.

But up at the farm in North Brooklin, Maine, that he and his wife, Katharine Angell White, bought as a second home, White found his peace.

It was there that he also found the inspiration for his best known work. A spider he watched in his barn as he tended to his animals began to fascinate him, even as he brooded over the death of a pig he had tended. (White was no hypocrite – he struggled with the moral questions involved in tenderly raising farm animals only to kill them for food – yet he still mourned the death of his pig.)

But unlike his earlier children’s classic “Stuart Little” (whose subject he said came to him in a dream), “Charlotte’s Web” was a work born of careful consideration.

Before he even started writing, White spent a year researching spiders. He also thought long and hard about his barnyard characters and the kinds of personalities he wanted to give them. Although he admired the work of Walt Disney, White wanted to be sure to stay away from overly cute depictions of animals who talked and reasoned too much like human beings. Instead he wanted characters such as a rat who seemed authentically – and even a bit vilely – ratlike, and a pig who seemed gleefully and unself-consciously piglike.

White succeeded in giving us a book that perfectly balances a story full of human appeal with an atmosphere that is genuinely barnlike. The magnitude of his success is reflected in the status of “Charlotte’s Web” as perhaps the bestselling children’s book in US history.

Sims wisely doesn’t try to give us all of E.B. White in his selective 244-page biography. (With notes and bibliography the whole book weighs in at about 300 pages.) But he does give us enough to make clear how much of himself White invested in this masterpiece.

“The Story of Charlotte’s Web” is a paean to a great work and a window into the uniquely gifted man who created it.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s books editor.