A presidential sex scandal, 1884-style

journalist Charles Lachman argues that former US President Grover Cleveland once raped a young woman but successfully covered the scandal up.

Did Grover Cleveland's presidencies mask a major sex scandal?

Ask a history buff about Grover Cleveland, and three things might come to mind: He was on the $1,000 bill, he served two non-consecutive terms, and there was a fuss over an out-of-wedlock baby.

"Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?" his opponents chanted as he first ran for president. "Gone to the White House, ha ha ha!" his supporters responded when he won.

Other than that, he seems like just another one of those dull-as-dishwater chief executives from the late 19th century. Cleveland, Hayes, Harrison, the guy with the walrus mustache and the… ZZZZZZ.

Well, wake up, dear readers! There's a lot more to Cleveland than yet another big mustache, as journalist Charles Lachman reveals in a new book. He believes, as many in the 1880s did, that Cleveland didn't have a consensual fling that produced an inconvenient child. He claims the future president actually raped a young woman, conspired to take the resulting baby from her, and covered the whole thing up.

Whatever the case, the scandal nearly cost Cleveland the presidency. Only in the final weeks of the 1884 campaign did the tide shift thanks to a minister's amazingly ill-timed jibe about Cleveland's immigrant-heavy Democratic party being one of "Rum, Romanism and Rebellion."

Lachman, executive producer of TV's "Inside Edition," proved his writing chops in his 2008 book "The Last Lincolns," a fascinating chronicle of the sad decline of you-know-who's descendants.

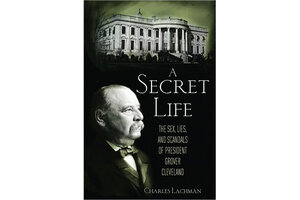

A Secret Life: The Sex, Lies and Scandals of President Grover Cleveland (which comes out on Monday) is another success, a blend of sharp detective work – he even finds out what happened to Cleveland's supposed son – and history that reads like a gripping novel.

This week, I asked Lachman about the truth behind the scandal, his own desire to set the record straight, and a president's surprising relationship with a glamorous young woman who didn't believe the rumors (or at least never said she did).

Q: How big of a deal was it that the women at the center of the scandal came forward and described the alleged assault?

A: It was unheard of for a woman who had been, as she says, raped, to speak about it in a public way. She submitted an affidavit. It was quite remarkable.

Q: What risk did she face by coming forward?

A: Her reputation had already been defamed. Cleveland's allies concocted this story that she was – in the phrase we'd use today – a slut. That she had between two and four relationships with leading men in the city of Buffalo, NY, and didn't know who the father was, that it could have been any of these four guys. That Cleveland, as the only bachelor in the group, "bravely" came forward because he wanted to save his married buddies from the shame of it being revealed that they'd had an affair with this woman.

Q: In fact, you believe she was sexually assaulted at her home.

A: Two people know the truth, and they've both been dead for more than a century. We'll never know what really transpired in that room. We do know that she was the only one to swear in the form of an affidavit, witnessed by a lawyer and her son, as to what happened. I find her a totally believable woman.

Q: How did the media of the time report on the allegations against Cleveland, which appeared during the presidential campaign of 1884?

A: A lot of newspapers felt that the details were too salacious to even report on. Some of those decisions were based on politics; a lot of the Democratic newspapers never ran a word about the scandal. When they did, it was only when their supporters conducted internal investigations that "cleared" him.

The Republican newspapers, on the other hand, went full steam ahead, reporting on the scandal for political reasons.

Q: What did the scandal mean for his presidencies?

A: He was never a beloved or particularly popular figure among the American electorate. Part of the reason, I believe, is the lingering affects of the scandal.

Q: Amazingly, he married a woman he'd known as an adult when she was a baby. She was the daughter of a Buffalo man whose own reputation was smeared by Cleveland's allies, who said he'd had a dalliance with the woman in question. What struck you about all this?

A: It could not happen today. Imagine the uproar that would take place if a sitting US president, elected as a bachelor, announced he'd fallen in love with a college senior, and by the way, he had known the child since babyhood. And by the way, he's in effect her guardian.

Q: And by the way, she's a looker, right?

A: Right. Can you just picture what would happen in the modern times? The curious thing I found was that there wasn't really an uproar. People were charmed by her, and there was a sense that our bachelor president was finally finding romance. This buried a lot of the undercurrent of concern that some people certainly had.

And we've grown to understand how inappropriate and over the top such an relationship can be. That was a different time and and a different age. People let it slide.

Q: People like to connect the escapades of men like Kennedy and Clinton to their personalities and presidencies. Do you see a connection here? Was he a risk-taker like them?

A: He was not a risk taker, but he was bullheaded, and he had a terrible temper. His personality was prickly and difficult, a hard man to get to know although he had deep friendships with a lot of men.

It's a difficult question to compare him to JFK or Bill Clinton. Cleveland was never a womanizer, and I don't think he particularly enjoyed the companionship of women. This was a guy who liked being in the company of other men, who liked to go to bars, and who liked big meals.

Q. Have you gotten a reaction from his family?

A: There are a lot of Clevelands around, and I don't anticipate they'll be particularly happy this. I've heard unofficially that they were very upset.

I've had the cooperation of Maria Halpin's family [the woman at the center of the book], and they're very pleased.

Q. Why did you write this book?

A: The more research I did, the more I realized that the story that had been written was not the story that had happened. It proved irresistible that I could write something that could change the way we see this historic scandal and this transformational president.

I just felt that it was time to tell the truth of what really happened.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.