Baseball's top numbers guy tackles true crime

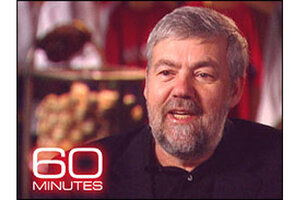

In "Popular Crime" baseball guru Bill James ponders centuries of blockbuster American crimes in search of greater meaning.

James says that the process of eliminating crime from our society is "so slow and so gradual that one can only see the progress by staring back across the centuries."

In the beginning, there were bats, balls, and bases. Then along came Bill James, a numbers cruncher who changed the way that baseball fans think about the game. He discovered that sacred statistics like batting averages and RBIs weren't the best ways to measure success and failure.

Now, James is tackling a new topic: true crime. In his newest book, he ponders centuries of blockbuster American crimes in search of greater meaning.

Popular Crime: Reflections on the Celebration of Violence turns out to be a gloriously rambling trip through justice, injustice, and everything in between.

When he's not creating a frame for understanding crime, James – a longtime aficionado of true-crime books – throws in opinions about famous cases. He lets at least one famous would-be murderer off the hook while confirming the guilt of accused killers who still have strong defenders. Most surprisingly, he backs a theory about the Kennedy assassination that sounds astoundingly unlikely but isn't the usual ludicrous conspiracy.

I asked James about our obsession with celebrity crime, the lessons he's learned, and the difference between a good true-crime book and a bad one.

Q: Plenty of high-and-mighty people act appalled when the country gets obsessed by celebrity crime instead of paying attention to, say, poverty or the deficit. Why are stories of true crime are actually worth our attention?

A: Crime stories reveal things about human nature that we keep very carefully hidden most of the time. We're fascinated with crime cases because we're fascinated by what goes on in people's heads, really deep down where you can't normally get to.

We are in a long process of eliminating crime from our society, a process that was thousands of years old before the Romans. The process has come a great distance since the time of the Romans; it has come a good distance in the last 150 years; it has come some distance in our lifetimes, in the last 30 or 40 years. But the process is so slow and so gradual that one can only see the progress by staring back across the centuries.

Eliminating these terrible events from society is not one problem. It is, rather, hundreds of similar and interlocking problems, which we attack one at a time. Crime stories are the knowledge base for that campaign, that endless and eternal struggle to rid the world of events of this nature.

Q: In your years of reading about true crime, what are some of the major lessons you've learned about the justice system?

A: • Well-meaning people create injustice because they are absolutely convinced of things that are not true.

Prosecutors dig in and double down on convictions in cases in which they are just absolutely wrong. Prosecutors don't want to convict anyone who is innocent. So when they accidentally convict someone who is in fact innocent, they very often – and I would say almost always – go into denial. They begin to insist that the accused/convicted person is in fact guilty, even if the evidence to the contrary is obvious and overwhelming.

The best protection against injustice is humility.

• Don't beat up the police and prosecutors because they can't always figure out what happened; the good Lord did not make any of us omniscient.

• If you leave the law to the lawyers, you will have a justice system that works very well for lawyers.

The lawyers think we should all "respect" their domain by staying out of their way. Periodically, the system stops working, stops recognizing the obvious.

We went through a period in which people could be acquitted because they were insane and released weeks later because they were (no longer) insane. The lawyers were fine with that. We have a situation now in which crazy people roam the streets in great number. The lawyers are fine with it.

Periodically it is necessary for the public to butt in and point out to the lawyers the obvious irrationality of the law.

Q: What do you think the media does wrong when it comes to popular crime?

A: The media does much more right than wrong, and much more good than harm. A spotlight is almost always helpful to see the truth, unless the spotlight is too bright, too harsh, too glaring, as in the Casey Anthony case, JonBenet, OJ. Short of that, the press is usually helpful to the cause of justice.

Q: What makes a good true crime book? And a bad one?

A: What makes a good crime book is depth: the ability to engage the reader on something more than a superficial level.

What makes a bad one is a rush to judgment and emotional piling on. You're writing about terrible events; it's not helpful to constantly remind the reader how ghastly they are.

Q: What does your approach bring to the understanding of popular crime?

A: Perspective, I hope. I tried to use interesting cases to draw attention to interesting questions, questions about our society that affect us all, and I tried to speak about those issues as thoughtfully and constructively as I could.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.