Meet the man behind the Ponzi scheme

Who was this Ponzi guy? Author Mitchell Zuckoff explains.

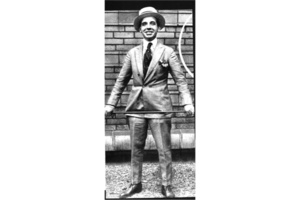

Charles Ponzi, the original Ponzi schemer, was an Italian immigrant, "a razzle-dazzle kind of guy" with "tremendous charisma."

Courtesy of Mitchell Zuckoff

We haven't heard the term "Ponzi scheme" much since Bernie Madoff became a household name. But then Rick Perry used the words this week to describe Social Security. It's a claim that, if true, would make Madoff's scam look as significant as a third grader's crooked lemonade stand.

Pundits immediately questioned Perry's statement and wondered if it will hurt his presidential prospects. As for me, I started thinking about a remarkable character named Charles Ponzi, whose story unfolds in Mitchell Zuckoff's enjoyable 2005 book Ponzi's Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend.

Zuckoff took some time off from promoting his new bestseller, "Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure, and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II," to talk about the legacy of this Hall of Fame fraudster.

Q: Who was this guy Ponzi?

A: He was an Italian immigrant who came here in 1903 and, like so many immigrants, was looking to make a fortune. He had no success, and ends up in Boston in 1917.

He comes up with this idea about opening an import/export company and [hears about] something called an international reply coupon, a way to send a self-addressed, stamped envelope from one country to another. It's almost like a form of global currency, used only to buy stamps.

He thought he could buy these things cheaply in countries whose currencies were depressed, bring them to the United States, transfer them to stamps, and make money.

On paper, it was actually feasible. This is the idea of arbitrage: buy something in one place at a lower price and sell in another place at a higher price. The problem was that there weren't enough international reply coupons printed on the planet to pay back even the first group of investors. There wasn't a market for this.

Q: How come people didn't figure this out?

A: He was a razzle-dazzle kind of guy, and he had tremendous charisma. He just said he'd figured out a way to do this, and he had a secret method. Most of all, his promises were so amazing. He'd double your money in 90 days.

The two sides of the human brain were working against each other. It was too good to be true, but people also thought it was too good to miss. And at first, he was able to pay back money to other people. He was using the classic Ponzi scheme: paying old investors back with money from new investors.

Q: Were there Ponzi schemes before Ponzi?

A: They were called "robbing Peter to pay Paul" before Ponzi. We remember Ponzi because he had this amazing combination of charisma and great success, at least for a brief time. And it was this moment in 1920 where money became king and newspapers were all over it. He hit that sweet spot of money and media that elevated him and made his name indelible.

Q. Has "Ponzi scheme" lost its meaning?

A: It runs the risk of that happening, as people talk about Social Security as a Ponzi scheme. It's at risk of losing its true meaning, which is a financial fraud by design in which one person convinces some number of other people to invest with him or her on promises of huge returns that are impossible.

Q. Why isn't Social Security a Ponzi scheme?

A: No one is being misled, and we're being told how it works. No Ponzi schemer tells anyone exactly how it works. The purpose of a Ponzi scheme is to trick people, to take the money and run.

Q: Are Ponzi schemes big these days?

A: The Ponzi scheme thrives in bad times. Obviously now the greatest of them all is Madoff, as far as we know.

There are so many variations on them. Madoff's variation was evil but it was also elegant: unlike Ponzi himself, Madoff never promised extraordinary returns.

What these people wanted was steady returns. The market is a scary place, and all these people wanted to know was that they could count on their money growing 8, 10, 12 percent a year, year in and year out.

For each one of these schemers, part of their dark genius is understanding their audience and finding appeals that work to separate them from their money. They know how to tailor their promises to their audiences.

Q: Could Ponzi schemes ever go out of style?

A: Because of the endless variety and human nature, they will be around a lot longer than you and me.

Randy Dotinga is a regular contributor to the Monitor's book section.