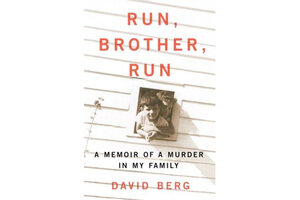

'Run, Brother, Run' author David Berg discusses his brother's murder – a crime made famous for the wrong reasons

Berg's memoir chronicles the death of his brother and the aftereffects of the crime.

'Run, Brother, Run' by David Berg is the story of a disapproving father, a son who wanted to please him, and a grief-stricken brother's road to peace – all grounded in the peculiar culture of Houston, Texas.

Judging by media coverage, the most notable thing about the new book Run, Brother, Run: A Memoir of a Murder in My Family is the last name of the alleged killer. It's Harrelson. As in Charles, the father of the actor Woody Harrelson.

But there's much more to this story than a link to celebrity. Attorney David Berg, whose brother Alan was murdered in 1968, is wry, wise, and heartbreakingly perceptive as he chronicles the extraordinary lives of those around him. He and his brother both struggled to please a difficult and unscrupulous father. Alan ultimately followed the boys' father into a life of shady business practices. His lifestyle brought him into contact with underworld figures – including alleged contract killer Charles Harrelson (who was charged with Berg's death but finally acquitted).

Berg survived the death of his brother and ultimately – after immense emotional pain – found a path forward. "Run, Brother Run" isn't one of those inspirational true-crime books that boast of victims who forgive or criminals who find redemption. His story is much more realistic (Berg finds plenty that's unforgivable, especially in himself) and much more powerful because of it.

In an interview, I asked Berg about the major elements of his story – the state of Texas and the city of Houston, a disapproving father and a son who wanted to please him, and the grief-stricken author's road to a kind of peace.

Q: Houston, where you lived in the 1960s, plays a major role in your memoir and even becomes a character in itself. How does Texas affect your family's story?

A: I remember driving across Texas and loving the freedom as I barreled down the road toward a different kind of life.

But Texas also had a great deal to do with my brother's death in how a man like Charles Harrelson could live and prosper and not be sent to jail for a very long time, how he could be acquitted of my brother's murder because he was tried in a rural, Southern and bigoted jurisdiction.

Q: What was Houston like during this time of incredible growth when it lurched toward becoming one of the five biggest cities in the country?

A: Houston was growing and out of joint, out of kilter, a pinball banging in one direction and then another, a mirror image of my family's life.

Nobody was actually from Houston. They were all from somewhere else. There were people in search of fortune, from good families and bad families, producing a culture as wild as the wells being drilled there.

Q: Did they like it there?

A: Everyone in Houston is ambivalent about Houston. Very few people say, "Man, I love this place, and I never want to leave it."

Q: You write about the influence of your father over the lives of you and your brother. What role did he play?

A: Machiavelli writes that the world conspires, usually in the form of a disapproving parent, to obscure our talents and gifts even from ourselves. The sooner you're able to shake that bond, the more likely you are to succeed.

Even up until the moment of his death, my brother Alan was still seeking his father's approval. He was smart and funny and a very capable guy and a great salesman, too, but he never understood that about himself. Up to the moment he was murdered, he was still seeking Dad's approval.

Q: What about you?

A: Somehow, I knew my father's approval was not worth winning.

Q: How did this tragedy affect you?

A: I know that I was ashamed of the way Alan died on some subconscious level, and I was ashamed of being ashamed. I think I poured all of that anger and embarrassment into my practice and the way I lived my life. It was like rocket propulsion.

Q: In your book, you don't spare yourself from blame. You're even too hard on yourself at times. What's behind that?

A: I don't know of a person who's lost a sibling who doesn't find some way to blame themselves.

My brother was a father figure to me, really the only father I ever had, and what I see now is that I blame myself for something I could have never done then: Take a different seat at the table, take his hand and say: "Don't screw up anymore, you've got to get out of this business."

But it wasn't our relationship.

Q: What advice would you give people who are recovering from tragedy?

A: What I would not advise people to do is what I did. When I began to write the book, 40 years after Alan died, I realized that I'd never talked about him, not to my sons, not to anybody. Rarely did I mention him and never how he died.

I took a kind of macho pride in that. I'd spared my family from any burden from Alan's death. But nothing helped me as much as writing this book. I left a great deal of my anger and a lot of my memories on those pages.

Q: What's the best way to move forward after emotional trauma?

A: The first thing I would tell them to do is to take some time before they seek help to let their feelings sink in. But fight mightily against self-pity. It's toxic. Once you indulge in self-pity, you're writing yourself off.

And I suggest getting therapy. You don't need to load up your friends and relatives with the tragedy that's befallen you.

I encourage people to find their own gifts, their own talents. Everybody's got a gift and talent, but it may be obscured, most often by a disapproving parent. You have to throw that off and pitch yourself into what you're good at doing.

Find what you love and pursue it with passion. That's good advice, tragedy or not, and it's especially important when you're caught in the maelstrom of grief.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.