'The Pope and Mussolini' author David I. Kertzer discusses the surprising relationship between the two men

What actually passed between Pope Pius XI and Mussolini? Kertzer draws on newly released records to find out.

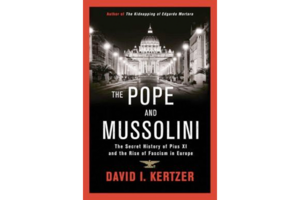

'The Pope and Mussolini' is by David Kertzer.

They were a match made in Rome, far from heaven: The leader of the world's most powerful faith and the dictator who introduced the world to fascism.

Both authoritarians, Pope Pius XI and Benito Mussolini clearly shared some common ground. But they were never close, and eventually a rift would grow and threaten their uncomfortable partnership. But would it be enough to rip them apart?

The stunning story of these two powerful men unfolds in "The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe," a remarkable new book by historian David Kertzer.

Drawing on newly released records, Kertzer authoritatively banishes decades of denial and uncertainty about the Vatican's relationship with Italy's fascist state. The pope and the dictator played a kind of diplomatic chess, jousting for power while endlessly worrying about their vulnerabilities to each other. And then a man named Hitler entered the picture.

In an interview, Kertzer explains the church's relationship to fascism, ponders what would have happened if the pope had fought back, and reveals his most surprising findings.

Q: It's amazing to imagine that the Catholic church cozied up to fascism. How did that happen?

We see things retrospectively in terms of where fascism ended up. But under Pius XI, fascism was totally new, an Italian invention headed by Mussolini – a bunch of former left-wingers who became fascists at the end of the first world war.

As for the church, things were very different than they are now, post-Vatican Council. It's not all that long ago when there was really a much more authoritarian, medieval vision in the Vatican and the church.

There was no sympathy for multi-party democracy in the church at the time. Popes thought it was better to work with an autocratic system. You could have guarantees through a police state that the church will retain rights like freedom from abuse. The church didn't believe in the freedoms we worry about – freedom of speech, of religion, of association.

Q: Why was the Catholic church so uninterested in democracy?

A: The liberal democratic state that separated church and state was an abomination that needed to be overturned. Fascism pledged to do away with much of that, and it was viewed as an unexpected gift from God by the pope at the time.

What people don't realize is that Italy is a modern nation that only came about in a war with the papacy. The popes still had the hope that they'd be restored to civil power, temporal power.

Q: Was Mussolini a religious man?

A: He didn't have a religious bone in his body, and I doubt the pope thought he did. But the pope once said that God works in mysterious ways and chooses instruments of his will from unlikely types of material.

For his own reasons, Mussolini saw church support as very important. He was willing to make a deal, to give the church a variety of benefits that it had lost.

The pope went into this with clear eyes. Later, he'd come to have regrets, particularly with the embrace of Hitler and the fear that Mussolini himself was trying to portray himself as a semi-divinity. But that was only later.

Q: What surprised you as you worked on this book and uncovered material in archives?

A: I was the first to discover that right after Hitler came to power, one of the first things he began to do was enact anti-Semitic laws, and it was Mussolini who sent his ambassador to plead with him to stop his anti-Semitic campaign because it was a bad idea.

Q: You also found that Mussolini worked behind the scenes against his supposed ally, Adolf Hitler, correct?

A: As late as 1938, Mussolini made a plea to the pope to excommunicate Hitler to prevent him from tyrannizing the world. Mussolini quickly regretted that, and the pope never acted on it.

Q: What is the most remarkable discovery you found in the archives?

A: The most dramatic is the deal that was negotiated by the pope with Mussolini to pledge the church to not publicly criticize the anti-Semitic laws about to be announced in Italy in exchange for beneficial consideration for Catholic Action, an organization of the laity under clerical control in Italy. This was the most precious thing to the pope.

Q: Was the pope was an enabler of Mussolini? Or would a term like "accomplice" be better?

A: I try to avoid those value-laden, judgmental terms.

But it's fair to say that the fascist regime was made possible by the Holy See for its own purposes. The Vatican played a key role in supporting the fascist regime.

Q: Could the pope have made a major difference in the history of World War II by standing up against Mussolini?

A: Italians didn't like the Germans. They'd just had a war with them. And Hitler was announcing Aryan supremacy, and no Italians thought that included them. In this context, if the pope had spoken up very strongly against all this, it could have had major implications for Italy's involvement in the war.

Q: What is the legacy of the story you tell of the dictator and the pope?

A: You have to put this in the larger context, in a certain kind of rewriting of history of the church and of Italy more generally. It's not just the Vatican that tried to rewrite its history, but Italy itself.

Q: The Catholic church, of course, is very different than it was in the 1920s and 1930s. What can we take from its evolution?

A: The positive note is that there was a recognition within the Second Vatican Council that their old theological ways had led to dangerous situations and unfortunate results.

There was a huge transition. The medieval, triumphalist vision – we're the only ones with the truth – went out. Pluralism and respect for inter-religious dialogue came in. This marked a very important move forward.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.