#1000BlackGirlBooks aims to connect black girls with books they can relate to

A sixth-grader from New Jersey has started #1000BlackGirlBooks, a social media campaign and book drive to collect books in which black girls are the main characters.

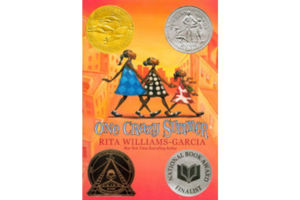

In West Orange, NJ, 11-year-old Marley Dias is seeking out books like 'One Crazy Summer' that feature young black women as protagonists.

Faced with a required reading list featuring books chock full of white characters, 11-year-old Marley Dias said she was "sick of reading books about white boys and dogs."

"I was frustrated ... in fifth grade where I wasn't reading [books with] a character that I could connect with," she told the Huffington Post.

So she decided to do something about it.

After a conversation with her mom, the sixth-grader from New Jersey started #1000BlackGirlBooks, a social media campaign and book drive to collect books in which black girls are the main characters.

Through her social media campaign, which Dias launched in November, she plans to collect 1,000 books by Feb. 1. On Feb. 11, Dias and her project partners will travel to St. Mary, Jamaica, her mom's hometown, to host a book festival and give the books to schools and libraries.

The goal of #1000BlackGirlBooks, says Dias, is to help young black girls relate to the books they read and the characters in them.

"[Representation] definitely matters because when you read a book and you learn something, you always want to have something you can connect with," she said. "If you have something in common with the characters, you'll always remember and learn a lesson from the book."

In fact, data suggests African Americans are sorely under-represented in children's books.

Since 1985 the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has been tracking diversity in children's books. Their findings are jarring: Of some 3,200 children’s books surveyed in 2013, only 93 were about black people.

In other words, in a country in which African Americans comprise at least 13 percent of the population, less than 3 percent of the new children’s books received by the Center in 2013 were about black people and even fewer were by black authors – about 2 percent.

According to the Center, the numbers have changed little since it began tracking them in 1985.

It's a disturbing trend that underscores the power of books – and the damage inflicted when literature doesn't reflect society, as UK children's laureate Malorie Blackman explained in 2014.

"Books allows you to see the world through the eyes of others," Ms. Blackman said. "Reading is an exercise in empathy; an exercise in walking in someone else's shoes for a while…. And fiction is an incredibly important force in shaping children and that's why fiction needs to be diverse."

"Books shape our understanding of the world and our understanding of ourselves, an occurrence even more pronounced in children. When parts of our society are scarcely represented in the books we read, we’re less inclined to know, relate to, and value those groups," The Christian Science Monitor reported in 2014. "Even more troubling, when minority readers, especially children, don’t see themselves represented in the books they read, they don’t receive the validation and affirmation of self that reading provides."

Which is why Dias's mother says her daughter's project is so important.

“For young black girls in the US, context is really important for them – to see themselves and have stories that reflect experiences that are closer to what they have or their friends have,” Dias's mother, Janice Johnson Dias, told the Philly Voice.

Dias is currently taking both cash and book donations for her book drive. Books can be sent to the following address: GrassROOTS Community Foundation, 59 Main Street, Suite 323, West Orange, NJ 07052