2018 resolution to worry less about lost books: How did it go?

One writer learned that letting books go – even for a bibliophile who counts them as a treasured possession – can be liberating.

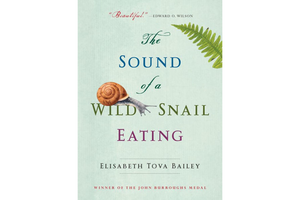

'The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating' is by Elisabeth Tova Bailey.

It’s been a year now since I posted a Chapter & Verse blog post declaring my New Year’s resolution to fret less about books lost from my personal library, especially those borrowed and not returned. My teenage son, Will, had borrowed my cherished copy of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essays and lost it on a bus – something he grieved about since he’s a typically responsible young man.

“In an age when the decline of reading is often lamented, I have a teenager who wants to read Ralph Waldo Emerson,” I told readers last December. “I’d rather have my books embraced and used, regardless of the risk, than simply entombed like the heirloom china that family members revere but don’t enjoy.”

Letting books go – even for a bibliophile who counts them as a treasured possession – can be liberating, I’ve learned these past 12 months as I’ve tried to honor my resolution. Inspired by his reading of Emerson, my son has been working his way through my books by naturalist Kathleen Dean Moore: Wild Comfort, Holdfast, Riverwalking, The Pine Island Paradox. He’s so in love with them that I might never get them back, and that’s OK. It’s been a joy to see him as enthralled as I am by Moore’s magical prose.

Will also recently borrowed "The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating," Elisabeth Tova Bailey’s chronicle of a tiny creature who comforted her through an extended convalescence. With my permission, he loaned it to a friend, and it probably won’t make it back to my living room shelf, either. Some of my other books have circulated this year, though the circle seldom brings them back to me. Slowly, I’m learning that the more you let books go, the easier it is to let them go. Practice helps.

Not that I haven’t thought from time to time about “Would You Mind If I Borrowed This Book?,” Roger Rosenblatt’s funny essay about the perils – and the promise -- of being a book lender. “It is the supreme selfless act, after all,” he says somewhat extravagantly of loaning a book. “Should we not abjure our pettiness, open our libraries, and let our most valued possessions fly from house to house, sharing the wealth?”

I suppose so. Readers are, I have found, an alternately exhilarated and discouraged lot – cheered by what they find in books, yet disappointed that the community of fellow bookworms isn’t bigger.

One way for lovers of literature to widen the circle of readers is to share their books more freely, far and wide, even if it means never see them again.

Or so I’m trying to remind myself as I renew my New Year’s resolution to let my library roam a bit, assuming that parts of it will find homes somewhere else.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is that author of A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.