Bernanke and Paulson: economy's two key crisis managers

The Fed chairman and the Treasury secretary face tough scrutiny as policymakers.

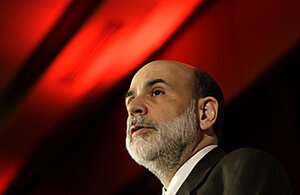

The Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition annual conference on Friday.

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

With America in deepening financial floodwaters, the task of crisis manager falls disproportionately on two Washington officials.

One is a longtime academic economist who is as fascinated with the Great Depression as some people are with model trains. The other is a former star on Wall Street, long the top banker at a top investment bank.

This storm began brewing well before they took the helm of policy. But dealing with it now becomes a defining moment in the public careers of both Ben Bernanke and Henry Paulson. For Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke, whose tenure comes up for review by the next president, the stakes include a simple personal matter: His job is on the line.

Neither is sitting idly by.

On Friday, for example, with the major investment firm Bear Stearns on the verge of collapse, a panic was averted thanks to intervention involving both the Fed chairman and Mr. Paulson, the US Treasury secretary. By Sunday, they had moved again, pushing the company into a sudden merger before stock trading began in the new week.

And on Tuesday, the Fed is expected to cut interest rates for its sixth time since September.

Given the scope of the challenges, it's not surprising that both men face criticism – sometimes for not doing enough, sometimes for doing too much. But for some experts, the outsized challenge leads to a more charitable assessment.

"They inherited a bad hand to play," says Paul Kasriel, director of economic research at the Northern Trust Co. in Chicago. "I don't see how it could be played much differently [to help the economy]."

Many economists believe the nation is now in recession. The depth and length of this economic downturn will hinge on the trajectory of a nationwide housing slump and a credit crunch. That's the aftermath of an epic boom in lending and leverage – making investments with borrowed money..

"Risk is being repriced and markets are deleveraging," Paulson said last week.

Among the things that look riskier now than a year ago: Houses, stock shares in financial firms, and even the US dollar itself.

The currency has sagged to historic lows against the euro. Home values are falling, wiping out trillions of dollars in consumer wealth. In this climate of fear, lenders are calling in loans instead of making them – a factor that caused an implosion at the venerable firm Bear Stearns.

The choices for Paulson and Bernanke are difficult enough that they will face criticism.

Among the top areas of concern:

Foreclosures. One of the loudest complaints against Paulson and the Bush administration: that they should back more aggressive measures to decrease a surging foreclosure rate.

Home prices may need to decline further for buyer demand to return. But a number of prominent economists now argue that homeowner defaults may cause home prices to overshoot on their way down – in a spiral that would damage consumer spirits and the health of banks.

A number of proposals are on the table, including the use of taxpayer money to buy troubled loans at a discount and then ease the terms for homeowners.

Paulson has urged banks to take such action voluntarily. Bernanke recently put a fine point on that notion, calling for banks to write down loan balances to reflect the reality of today's market prices.

But the response to Paulson's formal efforts has been slow, partly because so many loans aren't owned by banks but by pools of far-flung investors. Meanwhile, free-market conservatives have criticized both men for leaning on lenders.

Institutions. The Bear Stearns collapse hints at the possibility that credit-market turmoil could engulf more financial firms – large and small – this year. Already a number of hedge funds and mortgage companies have failed.

In its move last week, the Bernanke Fed (with the knowledge of Paulson and other officials) is framing the current meaning of "too big to fail." Bear is not among the dozen biggest financial players, but it is sizable and its tentacles do reach into a range of important markets.

Some finance experts say the Fed and other bank regulators – including the Treasury's Office of the Comptroller of the Currency – should be more wary of the "moral hazard" involved in bailouts. By riding to the rescue, policymakers make Wall Street complacent about managing its own risks in the future.

But many analysts agreed with the application of the too-big-to-fail doctrine Friday. In this case, the Fed extended credit to keep Bear afloat, and urged a rapid buyout of the firm. A sign of the level of distress: The bank J.P. Morgan paid $2 per share Sunday for a company whose shares had traded in the $50s a few days earlier.

In another emergency move over the weekend, the Fed announced a new way that it will loan money to other Wall Street firms under pressure, not just banks.

But the larger point is this: To avoid the need for bailouts, banks and other financial companies need capital in reserve.

"The major issue [for Paulson] now is to make sure banks have adequate capital," says Robert Aliber, a retired University of Chicago economist.

Last week, tucked into a larger array of long-term proposals for credit markets, Paulson made a plea for banks to move on this issue.

Interest rates. Low interest rates aren't a magic elixir for an economy where both borrowers and lenders are under stress. But many economists say that recent rate cuts by the Fed can help.

The problem: Others worry that cutting interest rates will fan inflation. The percentage of economists who see Fed policy as "about right" dipped below 50 percent this month in a survey by the National Association for Business Economics. The most frequently cited concerns in the survey were the inflation threat and the idea that lower interest rates might "bail out investors who should have known better."

In recent testimony, Bernanke said he expected consumer prices to rise more slowly than last year's 4 percent pace. But by some measures, bond-market expectations of inflation are edging up. That could pressure the central bank to shift away from efforts to stimulate the economy.

Brian Bethune, an economist at Global Insight says a key measure of money creation – considered the fuel for inflation – has been falling for several months. He says the Fed is right to focus on how to prevent a wider financial meltdown, which, if it occurs, could unleash the opposite problem of declining prices – deflation.

Currency. Paulson is under fire in some quarters for doing too little in his role as official spokesman for the US dollar as it declines – most notably against the euro. "Fixing this mortgage mess is important. But at the same time the Treasury should be working to stabilize and appreciate the dollar," Lawrence Kudlow, a conservative economist who hosts a talk show on CNBC, wrote in a commentary to clients last week.

Many economists say that a weaker dollar, for now, is in the US's interest, since it bolsters the competitiveness of US exports. Others counter that the dollar weakness is inflationary. Much of the rise in oil prices, for example, simply reflects a weak dollar. Conceivably, the US could work with other nations in a bid to firm up the purchasing power of the greenback.

Paulson, like virtually every Treasury secretary, repeatedly affirms that a strong currency is in the US's interest. In a TV interview Sunday, Paulson said that Bush policies and America's long-term strength are "going to be reflected in the dollar."